Competition or Centralization?

The idea of running the whole of society via centralized, administrative process is old. But the proponents of centralization never identify limits to centralization. Are there no tradeoffs?

I am on a train bound for the Imperial City north of Richmond.

Folks who have been reading my Substack essays with some regularity will have noticed that I’ve been posting much less regularly the last several months. A lot going on. Admittedly, we all have a lot going on.

I am right now off to DC to talk to various folks about some antitrust and contracting matters—specifically about franchising contracts. In May I’d been asked to submit comments in response to a “request for information” from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) about how franchising contracts work and, potentially, about how the FTC could weigh in and make them work better…

Beware government agencies endeavoring to make the world a better place, especially where free exchange between private parties is involved. Formal contracting is the kind of stuff that attends rather complex exchange, and any exchange can make for a messy business. It is reasonable to suggest that parties to contract anticipate the kinds of messiness and kinds of potential disagreements they might encounter. That’s why they craft contracts: in order to impose some structure on how to deal with eventualities that might put them at odds with each other. It’s all about managing relationships, which includes the prospect of having to manage conflict. But, one can see the government hazard: Government might understand evidence of messiness and conflict as scope for intervening and, somehow, making contracts “work better.”

Anyway. Some folks had read my FTC submission and suggested we talk. I’ve made a point of meeting in person rather than just plugging in to a video conference. Three-hour train ride up; three hours back. But I count my little venture to DC as a modest investment in a relationship that has some prospect of yielding good work over time. We will see.

One of the matters I’ve been tied up with involves content for a book I’m editing titled, Design and Implementation of Competition Policy. It may not conform to casual summer reading, but I will suggest that most of the content of the book will be accessible to readers who do not get up every morning wondering what the competition agencies are up to.

Submissions from contributors have started showing up, and I really need to give those attention. One of those submissions is something of a history of competition policy reform in Ukraine by a fellow I would count as the James Madison of competition law in Ukraine. He came of age as a judge in the Soviet era. He and his colleagues then went on to draft the original competition law back in the early 1990’s. He had the most central role in crafting the recent reform which is only just now going on the books.

Observers of the recent competition law reform had been looking to it to help “de-oligarchize” the Ukrainian economy. American officials, including American ambassadors, have said as much. EU officials have said that. So have Ukrainian officials. It is not obvious to me, however, that competition law will really give anyone the tools for … what? Expropriating the various holdings of the “oligarchs”? Would that not count as an arbitrary application of law, especially in an environment in which the authorities purport to respect property rights? I’m skeptical that competition law can enable a government that purports to respect the rule of law to somehow target people it does not like.

The contributor’s essay does give some clue about how oligarchy emerged. Was it the failure of the authorities to break up “state-owned enterprises” (SOE’s) into competing units during the early stages of “transition” from the Soviet era and into the brave new world of (ostensibly) free markets? Not obvious. SOE’s may have been transferred to private ownership in those early years, and coming in to ownership may have set up certain people as important presences in the economy. But, so what? The question remains: were there certain enterprises that would have been amenable to being broken up into competing entities, and did the authorities fail to do the breaking-up in those early years? Former Ukrainian president Poroshenko has set himself up as something of the king of chocolate in Ukraine. But, are we saying that all of the chocolate manufacturing capacity in Ukraine had been managed by an SOE and that those manufacturing units could have been sold off into bundles that would have comprised potentially competing enterprises post-privatization?

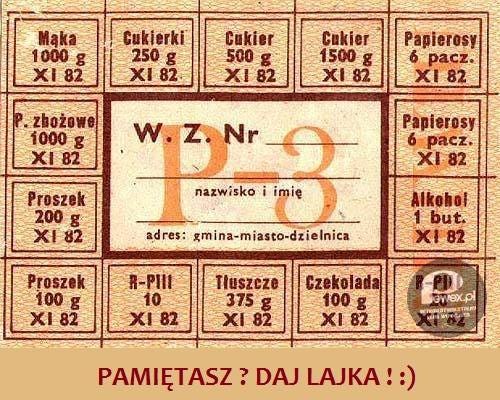

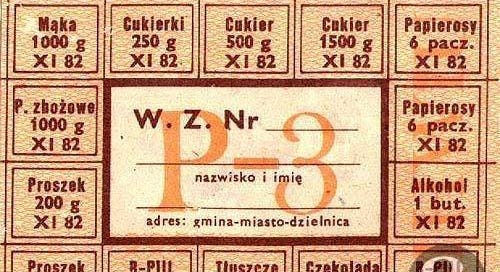

Perhaps. Meanwhile, within the last two weeks I did stumble upon this passage from a piece titled “Privatization in Eastern Europe: The Case of Poland” (Jeffery Sachs and David Lipton 1990, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2):

While some observers have worried that privatization in Eastern Europe should be delayed until after widespread demonopolization has occurred, we do not believe that monopoly power is an urgent problem in the industrial sector. Since most Polish industry is now subjected to strong international competition resulting from a policy of low tariffs and free trade, the problem of industrial monopoly is rather small even in sectors that are dominated by a few firms

That was 1990. Were Jeffery Sachs and David Lipton roughly correct? I think they posed a good point, and that point relates to the questions of (1) what it would mean to break enterprises up into competing units—is it really possible to “unscramble the eggs” in a given case? (2) Might these former SOE’s yet find themselves operating in a market that extends well beyond the borders of a given country, in which case such enterprises may yet expect to face much competition anyway?

Meanwhile, one clue about the emergence of oligarchy does come out of “James Madison’s” essay: There may have been an early push to set up a competition law and a competition authority, but other actors in government may have pursued competing objectives. These other actors may have endeavored to maintain Soviet-style management and to frustrate a post-Soviet distribution of property rights that might have yielded more competitive markets going forward. But, again, what SOE’s would have constituted good candidates for break-up? Any of them? Ultimately, is this idea that much Ukrainian commerce is directed by powerful people (“oligarchs”) more of a distraction, or was it something that could have been avoided? Evidence alone that there are powerful people out there means little. For, if it did mean something, why don’t we go after all powerful people? Should we, for example, Get Elon Because Powerful?

Meanwhile, I’d been struggling with the opening to the book. Consider this metaphor: It took Tolstoy the first 100 pages of War & Peace to finally hook his reader. It took him 100 pages to get all the atmospherics about high society in St. Petersburg out of the way and to set up his alter-ego, Pierre, to stumble by little more than dumb luck into the title of Count Bezukhov. By the time Tolstoy got around to crafting Anna Karenina, he had learned his lesson. He came out swinging with an intriguing opening line and opening vignette. He will have hooked his reader within the space of a few paragraphs.

So, can I hook my reader as efficiently as that? Can I hook the young person who would be disposed to think that competition is a bad thing; in place of competition policy, shouldn’t we craft collaboration policy? Or cooperation policy? Coordination policy?

I can open with such questions, but it would help to find a well known figure who may have said much the same thing. There are some nice passages from Lenin’s The State and Revolution (1917) which make the point, but leave it to Friedrich Engel to do a better job of it:

[A] new social order will have to take the control of industry and of all branches of production out of the hands of mutually competing individuals, and instead institute a system in which all these branches of production are operated by society as a whole—that is, for the common account, according to a common plan, and with the participation of all members of society.

It will, in other words, abolish competition and replace it with association. (p. 12)

That passage comes from Principles of Communism (1847). The Principles informed the crafting of The Communist Manifesto (1848) with the 30-year-old Karl Marx as co-author.

The Principles is, I think, more engaging than the Manifesto. The latter features much of Marx’s angry, heavy voice and introduces such turgid language as “the means of production.” Principles makes the basic proposition more accessible: Run everything just as the Capitalists would, but do it for the benefit of everyone, not just to serve the parochial interests of the Capitalists.

That sounds so eminently reasonable, no? But, I will suggest a few things. First, the statement makes it incumbent upon the proponents of a system of free-exchange and competition to make the case for competition over collaboration or “association,” as Engel’s calls it. At the same time, the proponents of “association” need to put much more energy into explaining why free exchange is a bad thing, because the alternative to free exchange is very, very unfree exchange regulated by the State. What could go wrong, right?

Second, the idea that we just organize the whole of an economy by “association” amounts to saying that we can run everything like one, big company. That amounts to running everything by centralized, administrative process. But, are there really no limits to scaling up administrative process to encompassing the whole of an economy? The proponents of Englesian organization-by-association do not even think to ask the question that there might be limits to scaling up administrative process. Indeed, might there be some important tradeoffs encountered in integrating more and more functions under unified, administrative control?

Enter organizational economists like Herbert Simon who himself made a point of framing the question from the perspective of “[a] mythical visitor from Mars” (Simon, “Organizations and Markets,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5 [1991]):

Suppose that it (the visitor I'll avoid the question of its sex) approaches the Earth from space, equipped with a telescope that reveals social structures. The firms reveal themselves, say, as solid green areas with faint interior contours marking out divisions and departments. Market transactions show as red lines connecting firms, forming a network in the spaces between them. Within firms (and perhaps even between them) the approaching visitor also sees pale blue lines, the lines of authority connecting bosses with various levels of workers...

No matter whether our visitor approached the United States or the Soviet Union, urban China or the European Community, the greater part of the space below it would be within the green areas, for almost all of the inhabitants would be employees, hence inside the firm boundaries. Organizations would be the dominant feature of the landscape. A message sent back home, describing the scene, would speak of “large green areas interconnected by red lines.” It would not likely speak of “a network of red lines connecting green spots.” …

When our visitor came to know that the green masses were organizations and the red lines connecting them were market transactions, it might be surprised to hear the structure called a market economy. “Wouldn't 'organizational economy' be the more appropriate term?” it might ask.

Were the perspicacious Martian to do some background research, he might observe that available economic theory does not give much insight into the question of why the “organizational economy” is structured the way it is. Why, the Martian might ask, does extreme centralization of the sort anticipated by Engels not emerge as a terminal state? Rather, he might observe that grand experiments with extreme centralization had proven problematic, and that economic systems had a way of reverting to forms that feature non-trivial degrees of market-mediated exchange—that is, decentralization. At the same time, however, he would yet observe diversity in the depth of the centralization both within the public sectors and private sectors across societies and time. What explains this variation?

Big questions, and no one has definitive answers. But, just being aware enough of the issues to situate oneself to ask the questions is important. And that is the biggest aim of the book: to raise awareness among young people who might think of getting in to the business of competition law, not because they want to preserve free exchange, but because they perceive, like Engels, that free exchange is the problem. But, so many ideas about how to organize the world without some accommodation for free exchange degenerate into calls to centralize everything under the control of self-anointed Philosopher Kings. That’s hardly novel and interesting.

How about if you just work on dissuading young people from going into "policy" in the first place? The last thing we need is more people with zero adult experience of navigating the real world helping to define what government does - - George McGovern's post-senatorial experience is a great cautionary tale.

"Beware government agencies endeavoring to make the world a better place" = too true!