What is to be done?

Regulation claimed to be saving the world cynically pits Our Democracy™ against Constitutional Governance. But constitutional governance can yet prevail.

This note links two sets of observations:

First, readers may know that the voters in Chile robustly rejected a wholesale reform of their constitution. “Reform” would be putting it charitably, for the reform would amount to replacing democratic process—the stuff we use for sorting through difficult, contentious policy issues—with progressive policy outcomes. Self-styled progressives market their preferred policy outcomes as “democratic” and denigrate actual democratic process as “fascist.” According to them, when the answers to policy questions have converged on progressive orthodoxy, nothing remains to “sort through”. We should merely codify orthodoxy and dispose of the renegades who won’t go along with it. The existing constitution may be a short document that codifies policy-making process, but we should replace that short document with a much longer document that codifies orthodox policy outcomes. We then call the result Our Democracy™.

For a very compact review of the specific matter in Chile, I’d refer the reader to “Why Chileans rejected a new ‘progressive’ constitution” from our friends at Spiked on September 9, 2022.

Second, frequent Spiked contributor Joel Kotkin has made quite a career the last few years documenting the feudalization of post-industrial society. A recent installment would be “Class Homicide,” September 7, 2022 at The American Mind. Long story short: Society had moved out of the Gilded Age into a more dynamic one that supported a burgeoning middle class populated by shop owners, entrepreneurs, and other small business people. But, over the last few decades, society has moved far along a trajectory leading to a neo-Gilded Age. “[H]ierarchy is rapidly replacing opportunity,” as “property ownership has become more concentrated” and “corporate concentration” in banking and tech has rendered a once dynamic economy moribund. The loss of dynamism amounts to an “assault on middle class mobility.” That, in turn, “strikes at the heart of democratic governance.”

“Our current drift back towards hierarchy,” he argues, “has many roots”:

[A]mong them the influence of technology, inattention to monopoly (under both parties), the pandemic, and addressing climate change. This is not so much a “conspiracy,” but the collective result of private actions driven by rational decision-making. Yet there has been a marked decrease in the percentage of all small firms in both the United States and Europe as larger firms continue to increase their share of the economic pie.

I have had the privilege of hearing first hand from people at the Small Business Administration (SBA) in the United States about the declining share of small business in the economy. My discussions with SBA started with an assignment to support a larger set of discussions between SBA and the antitrust authorities about the prospect of collaborating, somehow, to … support small business.

The antitrust enterprise, as classically conceived, is neither about promoting small businesses nor big businesses. Dare I say it, antitrust is about supporting the ultimate platform for non-discrimination and “diversity.” It is about supporting a decentralized system of free exchange. The system is decentralized in that firms, whether or big or small, operate autonomously and can contract with each other as well as with consumers to deliver goods and services. It is within such a system of free exchange that autonomous firms “compete” with each other in “markets”. “Markets” may or may not be entirely “free”—they may be heavily encumbered with regulation—but, the freer the market, the greater the competition… unless powerful interests do things to frustrate the entry of new competitors or to otherwise monopolize those same markets.

Note that one person’s “monopolization” might amount to nothing more than another person’s hard-nosed competition. That said, distinguishing monopolization from competitive conduct can make for a contentious matter, but it is the kind of thing that motivated antitrust. As classically conceived, the antitrust enterprise was launched to support market-mediated exchange or, the same thing, free exchange. Whether or not such exchange involved big firms or small businesses… that is not something that the antitrust enterprise has been designed to influence per se.

With all that in mind, it was not obvious that there really could be much scope for collaboration between the SBA and the antitrust authorities. There is this understanding out there that “small business accounts for two-thirds of employment in the economy”—something to that effect—and that therefore we should support small business. But that is a non sequitur. A small business operating out of a garage had a lot of success soldering together off-the-shelf computer components and selling the finished product as “microcomputers”. That was the original Apple Computer of the 1970’s. But the Apple of the 1970’s would not have been situated to do the same trick and come up with the tablet (the iPad) of 2007. It took a big business to assemble all of the inputs and complementary content to make that a successful venture.

Big and small will have their relative advantages, but the business of antitrust enforcement is not to tell private enterprise how to organize their businesses. But, that doesn’t stop SBA from actively promoting small businesses. Indeed, the SBA confuses correlation with causation. The SBA observed that small businesses have traditionally occupied a big share of the economy. More small businesses would yield a larger economy, right? In contrast, the antitrust authorities have traditionally remained agnostic about the distribution of firm size in the economy. Competition in certain markets will support an ecosystem populated by larger firms. Competition in other markets will support an ecosystem populated by smaller firms. Let it be.

That said, evidence that the share of the economy occupied by small businesses has been deteriorating may be a cause for concern. And here is where Joel Kotkin and I can both agree and disagree. We can agree that deterioration reveals that the economy has been losing its dynamism. Small business “deaths” have been increasing relative to small business “births” for some time. Something has been going on. On top of that, that something has put us on a trajectory descending into a bad, undemocratic equilibrium. (More on that below.) But we may disagree on some of the causes. Kotkin, for example, identifies our collective “inattention to monopoly” and something about “addressing climate change”. I would suggest that the continued expansion of regulation—much of it, ironically, motivated by the problem of “addressing climate change”—has induced sclerosis in the economy. That sclerosis manifests itself as (possibly unintended) cartelization of industries upon which the central authorities have imposed a regime of expanding regulatory demands.

Here is an example: “Energy Crisis” used to arrogate power.

There was much demand in the United States to Do Something in the wake of the “oil shock” and attending “energy crisis” of 1973. The United States eventually went on to establish the Department of Energy (DOE), and it situated within the DOE a regulatory program to establish energy efficiency standards for appliances (air conditioners, washing machines and the like). That was in the Carter years. The program remained mostly inert through the Reagan years of the 1980’s, but entities like the Sierra Club went so far as to sue the Administration to enforce the program. The Clinton Administration of the 1990’s did not require such inducement, but it was really the administration of George W. Bush that reinvented and elevated the DOE’s energy efficiency program. That was in 2007 with the Energy Independence and Security Act.

The object of the Act was:

To move the United States toward greater energy independence and security, to increase the production of clean renewable fuels, to protect consumers, to increase the efficiency of products, buildings, and vehicles, to promote research on and deploy greenhouse gas capture and storage options, and to improve the energy performance of the Federal Government, and for other purposes.

The Act situated an Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy in the DOE in order to “better coordinate efforts with the separate Industrial Assessment Centers and to ensure that the energy efficiency and, when applicable, the renewable nature of deploying mature clean energy technology is fully accounted for…”

The Act extended the purview of energy efficiency regulation to well more than appliances. Regulation went on to encompass an expanding portfolio of industrial equipment, commercial equipment and residential devices. The Bush Administration bequeathed this regulatory leviathan to the Obama Administration. The Obama Administration enthusiastically expanded it. The Administration justified the expansion by executive order. The order created a mechanism for coming up with a “Social Cost of Carbon” (SCC). The DOE could then mechanically justify new regulations by claiming that such regulations would reduce the SCC. That would amount to saving the planet, Because Climate Change™. Raising the carbon content of the atmosphere from 0.03% to 0.04% on a parts-per-million basis over the course of century would destroy life on earth. We could reverse that process (obviously) and save the planet, one regulation at a time.

A lot of small firms got swept up in “Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy” regulation (EERE), especially after 2007, and they continue to get swept up as the purview of EERE regulation continues to expand. All of these firms get stuck with decisions over whether to diminish their presences in certain markets or to entirely exit competition in those same markets.

A big part of their calculus involves not merely the costs of re-engineering their products but the costs of maintaining compliance with regulation going forward. The business of “regulatory compliance” thus amounts to a new layer of pure cost. A large firm might be better situated to economize on the costs of regulatory compliance by maintaining a whole division of people dedicated to tracking changes in regulations and to helping management decide how to comply with each newly ratcheted-up set of regulations. A smaller firm might just give up and sell out to a larger firm. Or that smaller firm might just liquidate whatever line of business had gotten ensnared in new, expanded EERE regulation.

What happens when the authorities extend the EERE regime to new markets? Conceivably, extending the reach of EERE amounts to a negative shock. Some number of firms may exit. Others will stay and assume the burden of regulatory compliance going forward. But, what happens when the authorities ratchet up the regulatory thresholds in future iterations of the regulation? Conceivably, the market exhibits no further exit. Firms will already have situated themselves with the capacity to manage compliance with ratcheted-up regulations. They end up replacing certain product lines with newer lines that satisfy the new regulations, and that is that. There is neither new entry nor exit from the market. We thus end up with a smaller set of larger firms ensconced in a regulatory cocoon. The more regulation expands, the more regulatory cocooning we get. The share of smaller firms in the economy diminishes, and we end up with a less dynamic economy policed by an increasingly sclerotic regulatory regime.

That all makes for a grand narrative, but does that narrative even approximately characterize how things have been unfolding since at least 2007?

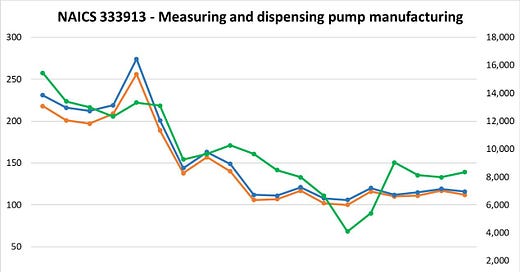

That is a big question, but—guess what?—I have assembled data to address just that question. I’ve been sitting on these data for a while. The data derive from more than 20,000 Federal Register filings relating to EERE from 1998 through 2020. I complement those data with data on firm populations that span 24 industrial codes. And, what do I see?

The most robust result is this: Whenever the Department of Energy has imposed a “Direct Final Rule” (DFR) on an industry, the number of establishments and even the number of firms has discernibly declined. The DOE represents DFR’s as a way of implementing new or updated regulations without having to go through the normal notice-and-comment process that usually attends the formulation of “final rules”.

The DOE justifies the use of Direct Final Rules by claiming that they represent broad consensus within a given industry about the implementation of proposed energy efficiency standards. The DOE holds workshops with industry “stakeholders” as well as with other “stakeholders” (climate activists and such). They come up with a rule, and impose it without soliciting comment from other stakeholders (consumers and, more importantly, firms not invited to the workshops). But, according to the DOE, the matter of implementing DFR’s derives from a process that involves collaboration between government and private enterprise. Which brings me back to something I posted last February:

[Progressives] believe in the merging of the power of the State with the power of erstwhile private interests—the corporations. We have a word for this: “Fascism”. Even some self-styled liberals get this. See, for example, the exchange between Bill Maher, Vivek Ramaswamy, and Marianne Williamson on just this point [at the 9:40 mark]:

Ramaswamy: “[T]his is about a merger of government and private enterprise that together is actually far more dangerous than either one [alone]. Blackrock, the world’s largest asset manager, managing over $10 trillion, got the deal to administer much of the COVID-19 stimulus, and many of their alumni now staff the [Biden] Administration… This is not a left-wing issue, it is not a right-wing issue, [the protests constitute] a rejection of this marriage of the private sector and government. They don’t really live in the moment of ‘social-distancing’? What I think is that, actually, we need more social-distancing between capitalism and democracy. Let the private sector operate; let government operate; keep them apart from one another.”

Williamson: “There is a word for it. There is a word for when the government is so tied, is so married to corporate interests. That word is ‘Fascism’.”

Maher: “Right.”

Ramaswamy: “Amen!”

Maher: “That is the actual definition of ‘Fascism,’ yes.”

I am thinking of showing off the DFR result at a forthcoming conference, but I haven’t showed it off to date for two reasons. One is that the data are good but not great. They amount to looking out on the universe with the telescope that Galileo had fashioned for himself in his own workshop. That telescope enabled him to discern the moons of Jupiter, but, beyond that, his telescope did not provide resolution great enough to discern much structure beyond the solar system. That said, my sense is that the authorities I have to face up to, the clerisy that governs social science research, really does not want to hear about how energy efficiency regulation is anything but great for planet Earth and good for the consumer. I get a lot of email about how programs in social science should support “sustainability” and, basically, should motivate the design of regulatory regimes to compel compliance of both private enterprise and consumers. Some of this stuff gets marketed as part of the design of “public-private partnerships” (PPP’s). PPP’s are in the business of organizing collaboration between the central authorities and private entities, all in the service of whatever objective the authorities have in mind. One can’t criticize PPP’s. One can’t criticize Fascism.

Which brings us back to constitutional governance.

The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA) has undermined energy independence and security and, more importantly, has enabled government to expand administrative guidance of the economy. The reader might recognize “administrative guidance” as a term of art from the 1980’s or 1990’s when everyone had been worrying about Japan taking over the world. Economic policy in Japan since at least the Meiji Restoration (1868) amounted to a Japanese flavor of “State Capitalism”. After seizing power in 1961, the military regime of Park Chung Hee implemented a Korean version of State Capitalism in South Korea. By about 1980, China launched its own program in State Capitalism. All of these programs have amounted to enlisting (generally large) enterprises as agents of government policy.

I would go so far as to argue that EISA 2007 and other such grand initiatives amount to efforts to build an American version of state capitalism. EISA amounts to just one chapter of the EU-ization of America. And all of that amounts to supplanting constitutional governance with the arbitrary rule of the administrative agencies. That administrative rule operates by expanding federal code by means of rule-making processes. The fact that those processes exist (by virtue of elected officials having passed EISA) amounts to an abdication of authority by elected officials who would otherwise have to organize regulation by running it through legislative, not rule-making, processes.

The EU operates out of the conceit that the Napoleonic Civil Code tradition constitutes a superior way of organizing the governance of the whole of society in contrast to common law processes. Governance-by-code amounts to operationalizing the worst, most naïve aspects of the Enlightenment. The expert class in government can design code that is rational and scientifique! They can identify the right policy objectives and then design code that implements those objectives. In which case, who needs democratic process? Actual democracy might get in the way of implementing the right policies. Democratic process should be suppressed. And yet, the best-and-brightest insist on calling governance-by-code Our Democracy™. It’s a sham.

In Chile, the left-leaning authorities endeavored to do something grander than merely pass a grand body of enabling legislation like EISA. They endeavored to supplant their entire constitution with a body of rational, politically-correct code. Constitutional governance amounts to setting up legislative processes for debating and designing legislative initiatives. In contrast, governance-by-code amounts to investing the central authorities with the capacity to make up rules absent the discipline of democratic oversight. The authorities can then just implement whatever outcomes they want without having to face the discipline of elections. So, good for the Chileans for seeing through the sham.

Meanwhile, back in the United States, legislators have ceded more and more power to the administrative agencies. A classic justification for ceding authority is that we should just leave governance to the experts, … because Governance-by-Expert has been working so well. The argument is that both society and the economy have become so complex that we can’t leave governance to the uncoordinated, chaotic and decentralized “market”. We can't subject it to the vagaries of electoral politics. We should invest the central authorities with more capacity to coordinate activity. But, that just amounts to organizing the economy like the Soviet system. Which, we know, has been done before, again and again and again. And it always fails. Which begs the question: What is it about free exchange that is so awesome?

It’s something about that freedom thing. Free exchange enables individual parties to pursue their crazy ideas—ideas that the central authorities would never come up with. A lot of ideas fail, but all of them together make for a more dynamic economy. “Let a thousand flowers bloom!”

What is to be done?

There are two broad avenues of affirmative attack. One pertains to the discipline of electoral politics (vote), and the other pertains to the discipline of judicial review (support litigation).

With respect to electoral politics: Yesterday our friends over at the Manhattan Contrarian posted a piece titled “California And New York: Do Not Back Off Your World-Beating Green Energy Schemes!” Francis Merton’s point, on my reading, is to allow the self-anointed best-and-brightest experts in California and New York to hang themselves. They have to be enabled to continue doing what they’ve been doing: Driving their states into the ground, thus setting a vivid contrast with states that have been more circumspect about handing over authority to the expert class.

Separately, we await more legal challenges to “Chevron deference” in the courts. Rule-making processes may be insulated from electoral accountability, but rolling back things like Chevron deference may restore some degree of judicial review of administrative initiatives.

I really admire your work. I suspect the regulators, being such, will never run out of things that they can find for regulation, whether needed or not. An outsider, like Trump, was wise in insisting some must go before making any new ones. Likely a good move but rare. The book of rules has grown exceedingly large over the years, well beyond any other than specialists can understand.

I suspect regulations stifle innovation - a very real cost. The US led innovation for a very long time with the notion that the market would sort the good from the bad. Nominally until recently, finances kept the failure rate high for poor performers. As the economy declines marginal firms disappear but regulation might be a part of that. Regulatory capture is one way the large guys keep the new upstarts in their place even before they can really compete. In the long term, I can't see how this improves the economy.

Without innovation by dreamers, even the green future is harmed. If carbon is really an issue we need a lot of innovation that the entire world might benefit from. State control as in many places has led to poor designs - notably the Chinese copy of a US nuclear reactor design is not widely used, not even by the Chinese! We can hope the new modular, factory built smaller US reactors might pave the way; some regulations have been set aside as unsuited for the newer designs, but we shall see.

I think your findings might be useful to Congress going forward. Why are there no teams to build a better case? This issue, like non-proprietary open systems voting designs seem stalled. I assume great forces exist to prevent change that might disrupt their cozy conditions.

Just a note: What Galileo saw through his telescope did not irritate the Church. Instead, they paid him handsomely to make them one. And they were funding him, and continued to fund him even after his first trial for heresy. This all while the Thirty Years War against the Protestants was raging, where the notion that any man could come up with his own interpretation of the Bible was something to fight wars over ....

See for instance: https://www.firstthings.com/blogs/firstthoughts/2011/09/the-myth-of-galileo-a-story-with-a-mostly-valuable-lesson-for-today/ or https://www.ncregister.com/blog/14-errors-revolving-around-galileo-and-how-to-clear-them-up

I have no particular liking for the Roman Catholic Church but the Galileo story is just another false narrative.