Crime in Trump’s DC – Update

It turns out that getting people off the streets for committing minor offenses sharply reduces the volume of major offenses like homicide. Who knew?

The main proposition here is that the people who commit dumb, silly offenses tend to be the same ones who commit really dumb, serious offenses. So, policing the silly stuff cuts down sharply on the serious stuff.

Stated differently: Getting people off the streets for having committed any offenses reduces the total volume of all offenses.

The Trump “surge” of policing in Washington, DC in August/September 2025 has reduced the volume of all crimes. That surge has included an increase in arrests on the part of the Metropolitan Police Department. So far, so good in that data suggest that these arrests have gotten many of the worst people off of the streets, but will the city authorities keep these perpetrators off of the streets indefinitely? If not, the volume of all crime, including the most serious crime, may increase to pre-surge levels.

* * *

On August 11, 2025, the Trump Administration invoked a provision in the “Home Rule Act of 1973” that would enable the federal government to assume control of the city’s police force for 30 days. The Administration also sent a few thousand national guard troops into the city to patrol selected neighborhoods. All varieties of crime discernibly decreased.

The DC mayor originally complained that the federal takeover was “authoritarian” but then, days later, proceeded to express “appreciation” for the “surge” in policing forces.

The 30-day mandate expired on September 10, and Congress did not elect to further extend the mandate. Even so, the national guard has maintained a presence in the city and continues to collaborate with the Metropolitan Police Department.

Crime remains diminished.

In an earlier essay, I speculated about why the sharp decline in crime might not survive the wind-down of the “surge,” but I also speculated about how the decline in crime could survive the end of the surge. The principal mechanism for a sustained decline would be getting bad guys off of the streets during the course of the surge and keeping them off of the streets after the wind-down of the surge. I further suggested that the decline in homicides was consistent with the authorities managing to apprehend bad guys, albeit for minor crimes.

It turns out that even the New York Times observed that the surge had resulted in an increase in arrests, although the Times complained that these arrests have concentrated on minor crimes. The surge had not thus far resulted in an increase in arrests for major crimes like homicide. But, why should it? My own point had been that the kind of people who commit the greatest share of serious crimes are also the kind of people who commit most of the lesser crime. And, so, sweeping them up for whatever crime should bring all crime down.

Data from daily Federal Surge Data Reports indicate that the Metropolitan Police Department had, indeed, increased arrests during the course of the “surge.” The question remains: Will those people who have been arrested be kept off the streets for some time?

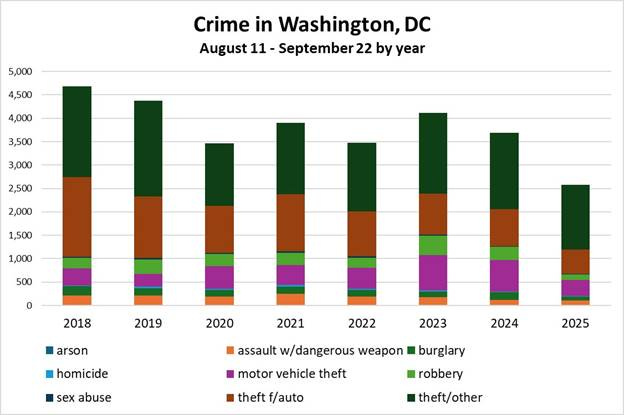

An appreciable amount of time has yet to pass, but we can still update our numbers of total crime since August 11. I present here an updated version of graph I had posted in an essay two weeks ago:

This graph indicates the volume of crime for the interval August 11 – September 22 for each of the years 2018 through 2025. This interval, August 11 – September 22, corresponds to the “surge” to date. Comparing the same interval over several years amounts to controlling for seasonal effects.

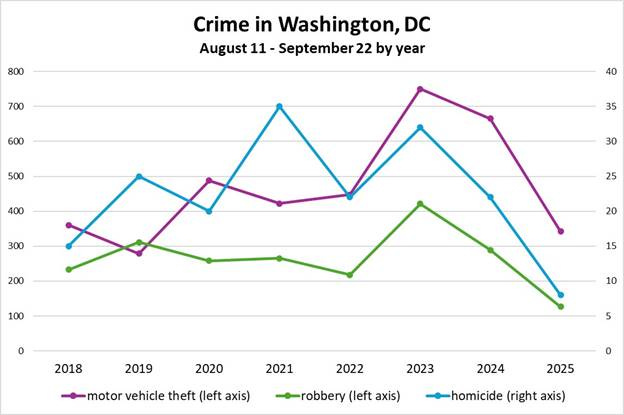

So, crime in time of the actual surge (2025) is notably lower than that of all other years 2018 – 2024. “Assault with a dangerous weapon,” “motor vehicle theft,” “robbery” are definitely down. Let’s zoom in on crimes associated more with “car-jacking” (“motor vehicle theft” and “robbery”) as well as on “homicide”:

We see, as in my previous essays, that motor vehicle theft started to become a more prominent phenomenon in 2020. Indeed, in earlier analyses, one can see that the rise in motor vehicle theft really looks like a COVID-era innovation. But, in 2025, it has diminished to the lowest level since the pre-COVID year of 2019. Meanwhile, homicide and robbery have declined to the lowest levels in the interval 2018 – 2025.

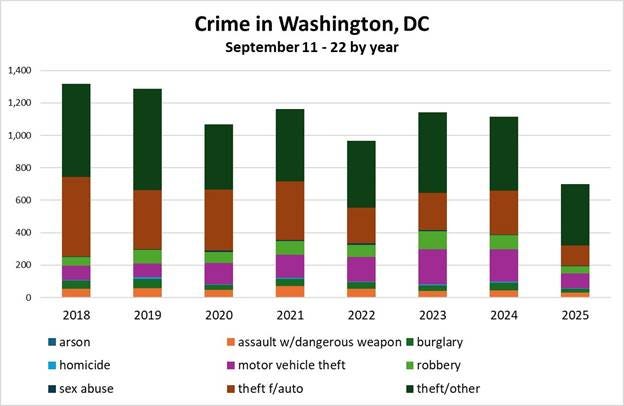

Now, the federal mandate to run the policing services expired on September 10. Has crime risen since then? How does crime in the interval September 11 – 22 compare to previous years?:

The profile of this graph maintains much the profile of the graph for August 11 – September 22. Crime is still down across the board.

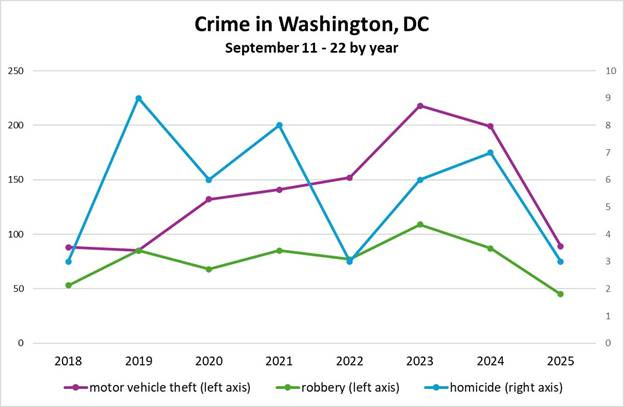

Let’s zoom in on motor vehicle theft, robbery and homicide:

It turns out that 2018 looks a lot like 2025 for the interval September 11 – 22. That interval made for a good week-and-a-half (by DC standards) in 2018. It looks as good again in 2025.

* * *

What to make of all of this? It looks like the most anti-social people who commit the great volume of very serious crimes also maintain vigorous careers committing less serious crimes. So, if you get them off the streets for having committed those less serious crimes, you can avoid most of the very serious crime like homicide as well as the various crimes that comprise “car-jacking.”

One can now see a rationale for things like “three-strikes laws.” These laws appear so harsh. Are we really going to warehouse people in prison from some years merely for having committed some number of minor offenses? An affirmative rationale would be the apparent fact that these are the same people who murder their neighbors and commit other serious offenses. Something like a three-strikes law … or six-strikes law or even a twelve-strikes law would have spared Iryna Zarutska a fatal encounter on the light rail in Charlotte, North Carolina.

One can also wonder if there is a flavor of “broken windows policing” at work here, although I am not certain. Going into this essay, I had the idea that “broken windows policing” amounted to some version of the proposition that taking care of the small stuff goes some way toward discouraging the big stuff. But, in its original formulation in “Broken Windows” (George Kelling and James Q. Wilson in The Atlantic, March 1982), it really was more about encouraging residents to respect higher aesthetics rather than submit to mischievous instincts and contribute to the physical degradation of the neighborhood.

Social psychologists and police officers tend to agree that if a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken. This is as true in nice neighborhoods as in rundown ones. Window-breaking does not necessarily occur on a large scale because some areas are inhabited by determined window-breakers whereas others are populated by window-lovers; rather, one unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing. (It has always been fun.)

…

Untended property becomes fair game for people out for fun or plunder and even for people who ordinarily would not dream of doing such things and who probably consider themselves law-abiding. Because of the nature of community life in the Bronx—its anonymity, the frequency with which cars are abandoned and things are stolen or broken, the past experience of “no one caring”—vandalism begins much more quickly than it does in staid Palo Alto, where people have come to believe that private possessions are cared for, and that mischievous behavior is costly. But vandalism can occur anywhere once communal barriers—the sense of mutual regard and the obligations of civility—are lowered by actions that seem to signal that “no one cares.”

But then there is this:

[T]he link between order-maintenance and crime-prevention, so obvious to earlier generations, was forgotten.

That link is similar to the process whereby one broken window becomes many. The citizen who fears the ill-smelling drunk, the rowdy teenager, or the importuning beggar is not merely expressing his distaste for unseemly behavior; he is also giving voice to a bit of folk wisdom that happens to be a correct generalization—namely, that serious street crime flourishes in areas in which disorderly behavior goes unchecked. The unchecked panhandler is, in effect, the first broken window. Muggers and robbers, whether opportunistic or professional, believe they reduce their chances of being caught or even identified if they operate on streets where potential victims are already intimidated by prevailing conditions. If the neighborhood cannot keep a bothersome panhandler from annoying passersby, the thief may reason, it is even less likely to call the police to identify a potential mugger or to interfere if the mugging actually takes place.

W.E.B. DuBois was one of the founders of the N.A.A.C.P. (1909). About 20 years earlier, DuBois spent some time living in Ward 7 of the city of Philadelphia, and it was out of that experience that he composed The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (1890). He many times distinguishes between “respectable and decent [working] people,” “some of a better class,” a “semi-criminal class,” and the genuinely “ignorant, vicious and criminal.” I have been meaning to read this book for some time, but I do wonder if buried in it might be some version of the proposition that getting the “vicious and criminal” semi-permanently off of the streets sharply reduces crime and broadly promotes the welfare of the neighborhood.

None of these ideas conform to politically-correct dogma, even if a civil rights icon like W.E.B. DuBois contributed to such ideas. And, anyone who has read any of my essays will appreciate that I explore a lot of politically-incorrect content. Because we shouldn’t live in lies and submit to the dogma.

I'm British, living in the UK. Is this an argument to say that we need more police on the streets all the time? Completely at odds with the Defund The Police movement.

In the UK we have a rapidly rising problem with shop lifting especially in London and the cities. The police here do nothing. There are even some politicians who say that Shop Lifting is not really a crime. But I think you ignore it at your peril.

On a slightly different slant, you've probably read about our issue with free speech especially on social media. People are being arrested for what many people call hurty-words crime. If you offend someone by a tweet and they complain to the police you might expect a knock on the door. It is sometimes recorded by the police as what they call a non-crime hate incident. The argument for it, they say, is that such 'hate speech' is a forerunner of actual crime and should be controlled and recorded.