Defunding the NGO Borg-osphere

Bad-by-design government procurement contracts with NGO’s may be generating waste, fraud and abuse on the order of $2 trillion a year.

“I have for some time viewed with alarm the spending policies of this administration. I cannot agree with those in the administration and in this body who would have us reduce taxes, increase spending, and finance resulting deficits by mortgaging our children's and grandchildren's future.”

That was Republican Joel T. Broyhill of Virginia speaking on the floor of the House of Representatives on June 18, 1964.

“Waste, fraud and abuse!” “Mortgaging our children’s and grandchildren’s futures!” For decades, these phrases have amounted to nothing more than empty rhetoric that Senators and Congressmen have tossed out on the floors of their respective chambers of Congress, and it has always been members of the party not in the White House that has deployed such language. But, when it has really come down to doing something about spending, they’ve rarely acted. The one exception might be the détente in 1996 achieved between the Clinton White House and the Republican majority in the House of Representatives in 1996 (the first Republican majority since 1952). That Congress and that White House managed to commit to “welfare reform” and managed to not expand spending. By the end of the Clinton Administration (2000), the country had even managed to generate a surplus in the federal budget. Federal spending (“net outlays”) as a share of GDP dipped as low 17%.

That 17% still amounted, historically, to an enormous volume of spending but was lower than the 19%-to-22% that had prevailed since the 1970’s. Indeed, spending as a share of GDP had not been that low since 1974. One can see this in the following graph that I downloaded from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis:

This graph shows that federal spending as a share of GDP peaked during the Second World War at about 41%. The next highest peak occurred during the COVID hysteria of 2020 when it exceeded 30%.

Meanwhile, the rare budget surplus of the year 2000 (when spending as a share of GDP was about 17%) was the focus of most of the political competition between the Republicans and Democrats at the time. Indeed, the debate as of September 10, 2001 was about how to dispose of budget surpluses that the Congressional Budget Office had projected indefinitely into the future. The Democrats, led by Nancy Pelosi, argued for expanding social programs. The Republicans, led by the administration of George W. Bush, argued for giving it back to the people by means of tax cuts. The events of September 11 changed priorities, and the projected budget surpluses turned into deep deficits.

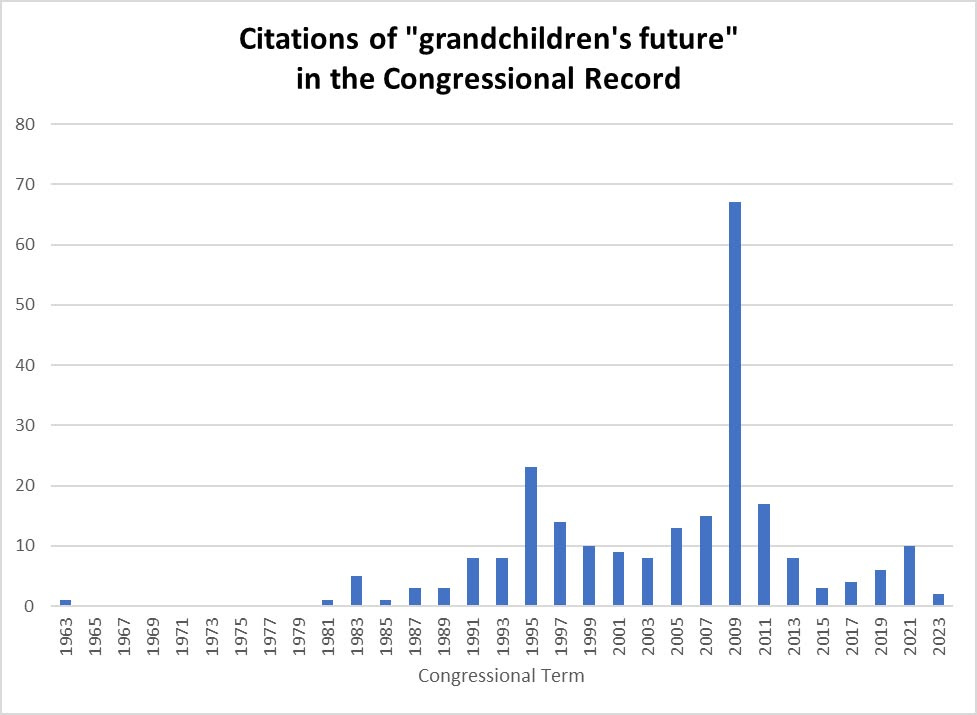

I searched the Congressional Record for expressions in the spirit of “deficit spending on the part of the federal government will ‘mortgage our children’s and grandchildren’s futures’.” Searching for “grandchildren’s future” yielded many such results. Here is a graph:

It turns out that Joel T. Broyhill’s expression of June 1964 was really just a one-off affair. Complaining about budget deficits really only got going during Ronald Reagan’s term in office (1981-1988). Expressions of concern about budget deficits picked up during the Clinton years (1993-2000) and achieved a peak during the Congressional term of 1995-1996. It was at that time that the Republican Congress and Clinton White House managed to pound out “welfare reform” legislation. But the biggest spike in expressions of concern about “mortgaging” the futures of our children and grandchildren came in the wake of the 2008/2009 financial crisis. Members of the Republican minorities in the Senate and House of Representatives complained about the big “stimulus spending,” bank “bailouts” and the structure of “Obamacare,” all in an effort to tap into the energy manifest in the new “Tea Party” movement.

It was out of the Tea Party movement that MAGA ultimately emerged. Tapping in to the Tea Party in time for the 2010 mid-term elections may have made for good fundraising, but Congress never managed to do anything about spiraling spending. Indeed, the government has been funding itself on auto-pilot in the form of “omnibus bills” and “continuing resolutions.” No one has been serious about cutting spending, although the Republicans did secure a majority in the House of Representatives in the 2011-2012 Congressional term. Thus entered the “Young Guns,” into House leadership: Paul Ryan, Eric Kantor and Kevin McCarthy. (Here is Eric Cantor’s 2010 book, Young Guns: A New Generation of Conservative Leaders on Amazon.)

“The time has come to move the country forward with a clear agenda based on common sense for the common good,” they exclaimed. “THERE IS A BETTER WAY.”

The Young Guns and the leader of the Republican majority in the House, John Boehner of Ohio, may have tapped into that “Tea Party” energy, but they did nothing with it notwithstanding the fact that they presented themselves as budget policy wonks. Meanwhile, the Democrats simply dismissed the “tea partiers” as—one guess: As ray-cists! Of course. Nancy Pelosi called them “Nazis.” Barack Obama referred to them as “tea baggers” (?) and complained in 2009 that these were people who “cling to their guns and religion.”

It was in 2009 that I first encountered some of these racist tea partiers myself. I was out for a run on one of my usual routes. This route would take me down and around the Capitol, and it was on a mild day in September that I ran into a sizable protest on the west side of Capitol, the usual place for protests of any sort. (I would say there were 35,000 to 50,000 protesters.) I ran back home, got my camera, and cycled back.

The themes expressed in this photo were much the themes expressed during the Capitol protests of January 6, 2021:

Here is an image of some “bitter clingers”:

At the time, this two-year old owed about $35,000 in federal debt. Sixteen years later, that 18-year-old owes about $115,000:

Here are some genuine “tea partiers” for you!:

Meanwhile, as of 2019, federal spending (“net outlays”) amounted to about 20% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In 2024 (the last year of the Biden Administration), it amounted to about 23% of GDP. In dollar terms: spending in 2019 was about $5.3 trillion (in current dollars). In 2024, spending totaled $6.8 trillion…

Now, what accounts for that extra $1.5 trillion in spending, that extra 3% of GDP? Can’t we roll back spending to 2019 levels? Even better, can’t we roll it back to year 2000 levels when spending accounted for 17% of the economy (about $3.1 trillion in current dollars). Why can’t we roll back current spending to $3.1 trillion and save ourselves $3.7 trillion? Where is that extra 6% of GDP or $3.7 trillion going?

As readers will likely know, much of that extra spending has funded the NGO Borg-osphere. In its closing days, the Biden Administration made a point of explicitly “Trump-proofing” federal spending, and that involved getting money out by the $tens-of-billions as well as committing the federal government to Biden-era levels of spending at least through the next year. This spending involves annual deficits of about $2 trillion, and unraveling that spending and getting the budget under control will amount to a difficult job—difficult, one may guess, because too many factions have an interest in keeping their spending going.

Here is an example of that NGO spending. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has set itself up as an NGO and has sued the federal government to compel it to continue funding the Conference’s mission of processing illegal immigrants and relocating them around the country. The Conference’s principal argument is that, “Given the continuing availability of appropriations, the Executive Branch cannot unilaterally and indefinitely refuse to fund those statutorily mandated services.”

I have a question for the Catholic bishops: Do your contracts with the federal government correspond to fixed-price contracts, cost-plus contracts, or fee-for-service contracts? Or something else? The question matters, because the structure of the compensation in contracts can help contain waste, fraud and abuse or facilitate waste, fraud and abuse.

Let me motivate this. As I’ve suggested in a previous essay, the beneficiaries of heavy spending have been arguing that the Executive can approve funding but really should not be permitted to cut spending. Instead, it seems that we should understand federal spending as drawing the federal government (the principal) and NGO’s (the government’s agents) into a particular kind of principal-agent relationship: the government commits to procurement contracts by which it either commits to making fixed payments over the course of a contract term or commits to “cost-plus” payments over that contract term. So, under a fixed-price contract, the government might say, “Here’s $1 billion; do your thing, no strings attached.” Under a cost-plus contract, the government might say, “Do your thing and report back what the costs of doing your thing ultimately amounted to; we will cover your costs and tack on an extra margin.”

If the government really does commit in formal contracts to making either fixed, lump-sum payments or cost-plus payments over some specified contract term—a one year term in the case of the Conference of Catholic Bishops—then the Bishops might have a good case. But, alternatively, if the relationships between the government and its agents (the NGO’s) are more in the spirit of on-demand services, then the government can stop making demands for services, and it can thereby stop paying fees to support those services.

I am getting the sense that the relationship between the federal government and the US Conference of Catholic Bishops is more in the spirit of the latter: The government maintains relationships with preferred vendors and calls on those vendors when and if it requires services. Contracts really amount to agreed-upon fee schedules. One can imagine, for example, that one item in the fee schedule would amount to a fixed fee for transporting a migrant cross-country: “Here’s $500; you choose how to transport the migrant, whether by bus or plane; it’s up to you, the contractor; if you can do it for less than $500, then you get keep the difference; if you expend more than $500, then you have to make up the difference.” Ultimately, if the government says, “We don’t need your services anymore,” then you don’t get paid. End of story.

So, how has the federal government structured its procurement contracts with entities like the US Conference of Catholic Bishops? Contracts that involve lump-sum payments or cost-plus payments would be susceptible to all types of cheating. The agent can over-report costs or under-supply services. Even so, the government might use lump-sum payments as ways of paying off favored constituencies: “Here’s $1 billion; go forth and provide ‘services’.” The same goes for cost-plus contracts: Just overbill the government for services that may or may not have been rendered. Basically, the government could use badly-designed procurement contracts to launder money and to lavish money on its friends in the NGO ecosystem. In contrast, would fee-for-service contracts be less amenable to manipulation?

Poorly-designed procurement contracts would seem to be a great source of “waste, fraud and abuse.” This phrase has never amounted to more than empty sloganeering, and, it turns out that this phrase has been much more prominent in the Congressional Record than appeals to “our children’s and grandchildren’s futures.”

The graph indicates citations of “waste, fraud and abuse” in speeches on the floors of Congress (in the Congressional Record) as well as in legislative initiatives. By “initiatives” I mean drafts of proposed legislation as well as actual legislation.

Again, citations of “waste, fraud and abuse” really got going in the Reagan years (1981-1988), peaked in the 1995-1996 Congressional term of the Clinton years, but they really got going as the Bush-era spending (2001-2008) started to ramp up. Much of that spending involved appropriations on the order of $80 billion every six months to fund operations in Iraq or Afghanistan. Sometimes the government was literally handing over bags of cash to selected warlords preferred vendors. “Bags of cash” amount to the ultimate fixed-fee contracts: “Do your warlord things and keep the change; please don’t tell us about villas on the Riviera or penthouses in Doha; we don’t want to hear about it.”

My own view had been that actual “waste, fraud and abuse” would be hard to identify, hard to remedy and might not involve the kinds of big savings we would need to secure in order to appreciably bring spending down. In contrast, the DOGE experience under Elon Musk’s guidance during this first 30 days of the Trump Administration seems to suggest that “waste, fraud and abuse” might actually amount to staggeringly large numbers. But, again, can big streams of spending be clawed back in 2025, or has “Trump-proofing” really frustrated any effort to make serious cuts in spending for at least a year? Can shifting from contracts that are badly designed by design to contracts that are more resistant to over-charging and fraud undo much of the Trump-proofing? Is bad contract design by design an important driver of the action? I think so.

My simple advice to DOGE: Concentrate attention on fixed-price procurement contracts and cost-plus contracts. Don’t worry as much about fee-for-service contracts… for now. Put those on the back burner.