Economists Throwing Tantrums

Economists have a lot to offer but insist on being worse than useless.

For some weeks now economists and economics-adjacent journalists have been complaining about the idiocy of Trump’s threats to impose trade tariffs. See, for example, the Wall Street Journal on “The Dumbest Trade War Fallout Begins.”

Observers note (correctly) that tariffs amount to taxes on imports. Sharp rises in these taxes likely induce sharp price increases. We experience a sharp bout of inflation.

The great weakness of these complaints is that the underlying analysis is less than superficial. The analysis, such as it is, fails to fold in the fact that this business of tariffs credibly amounts to a bargaining ploy, and the bargaining, it seems, spans a broad range of issues. Those issues include: high tariffs that other countries have long imposed on American exports, containment of the prodigious streams of illegal immigration, and the containment of the prodigious volume of drugs and human trafficking that attends that illegal immigration. Yet other pro-bargaining observers suggest that the larger aim of the threat of tariffs is to get countries like Canada and Mexico to stop operating as China’s agent in what really amounts to an Opium War against the United States.

That Opium War metaphor would require much more motivation than I am situated to offer. My objective here is to revisit (again) this larger question about how wars—whether trade wars, gang wars, or actual war wars—ever start. At first sight, the trade war business does look dumb, because it’s not immediately obvious how the party instigating the war benefits. Imposing tariffs may raise some revenue but may end up imposing much more cost on society as a whole. Mexico knows this, and the United States knows that Mexico knows this. The United States can then anticipate that Mexico perceives that a threat of tariffs is really just an empty bluff. So, Mexico “calls the bluff” by doing nothing. The United States then backs down and declines to impose tariffs after all. And, anticipating the prospect of having its bluff called and then revealing the bluff as just that (a bluff), the United States declines to threaten tariffs in the first place. The threat of tariffs is not credible. End of story.

Or is it? The threat of tariffs might not be credible in a one-shot interaction. That is, suppose a feature of the interaction is that one party has only two choices: impose tariffs forever after or not impose tariffs forever after. That would make for a strange game (would it not?), because we can imagine more elaborate (and more realistic) scenarios. Like, one party threatens to impose tariffs for just, say, a year, and then will revert to no tariffs. Or, maybe one party threatens to impose and maintain high tariffs so long as a counter-party maintains its own raft of high tariffs.

So, in place of one-shot interactions, we’re talking about a relationship that extends indefinitely over time. Threats may now become credible, and those threats may go far toward maintaining the peace.

There is empirical evidence about how the threat of retaliation can maintain the peace. A classic on this count is Trench Warfare 1914-1918: The Live and Let Live System (Tony Ashworth 1980). That book is all about how British and German soldiers on both sides of No-Man’s-Land learned to develop relationships—and to collude with each other against their respective High Commands to avoid killing each other. And so, artillery barrages might fall in No-Man’s-Land short of opposing trenches. A machine gunner might make the point of predictably raking the opposing line at tea time every day. Some gunners even learned to “loose off” to the melodies of popular tunes like “Policeman’s Holiday” with the opposing side responding with the refrain “bang-bang!”

The simplest economic theories of bargaining suggest that parties to really important exchange (like trade) should be able to avoid mutually costly trade wars. It becomes hard to rationalize why trade wars would occur at all. Why does cooperation sometimes breakdown. That was also an important topic of Trench Warfare.

It turns out that economic theory may have to do a lot of work in order to motivate why conflict might break out or cooperation might break down not as a matter of being “dumb” but, oddly, as a matter of being rational. One possibility is that parties to potentially fraught exchange may establish an agreement to not abuse each other, but what if that agreement is difficult to monitor? One party might cheat: We agreed to police drug traffic across the border, but there is so much money to be made in it; no one will notice a little cheating on the side. The other party might argue that, if we observe little spikes in drug traffic, we’re going to assume that someone on your side is cheating even if they’re not—and we will retaliate. The result is that, in an environment featuring costly and imperfect monitoring, we might observe the occasional episode of retaliation.

Readers may know that, over the last week, the Trump administration has threatened to levy high tariffs on goods coming from Mexico, Canada and Colombia. The business in Colombia involved the apparent fact that Colombia had reneged on an agreement to take back some “bad hombres,” some of “the worst of the worst.” Trump threatened tariffs and within a day Colombia cut a deal. So, no tariffs and Colombia would take its people back. Indeed, the Colombian president agreed to take these people back on Colombia’s own presidential plane. In return, the United States would lift the threat of tariffs—for now—and the Colombian president could say some tough things on Colombian TV.

Similarly, it took Mexico a weekend to similarly cut a deal with the United States. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum got to broadcast a lot of tough-sounding bluster on Mexican TV, but the president ultimately agreed to “immediately supply 10,000 Mexican Soldiers on the Border separating Mexico and the United States.” In return, the United States has agreed to not revisit the prospect of imposing tariffs for at least a month.

As of a Monday afternoon, Canadian authorities have made a point of talking tough. We will see how long they hold out.

In any case, the point of the Trumpian tariff threats seems, so far, not to impose tariffs for the sake of imposing tariffs but to threaten tariffs in order to seek concessions on a whole range of matters. We will continue to see where this goes, but the bed-wetting cranks and economists on X should probably take a breath and take time to observe the proceedings before polluting the media with more of their complaining.

Which reminds me: For the first time ever, I found myself pulled into a bit of an online spat on X. This was several weeks ago. An economist who maintains a non-negligible online presence was spouting off some very superficial nonsense about Trump’s tariffs. I simply made the point in very neutral language that we might understand the threat of tariffs as merely a leverage point in bargaining over a range of issues. This anodyne suggestion was met with a petulant, sarcastic response, with the correspondent ascribing to me certain views on matters about which I had offered no opinion. I would even suggest that not offering opinions on things not requiring opinions makes it a lot easier to talk to people about potentially contentious issues. But, some folks can’t be helped. The wisdom of Boethius comes to mind: Bullies are their own punishment by virtue of their inanity and anger. No need to pile on.

Meanwhile, readers might recall that, two weeks before The Election, “Twenty-Three Nobel Economists Sign Letter Saying Harris Agenda Vastly Better For U.S. Economy.”

What shocked me, however, was how vacuous this letter was:

We, the undersigned, believe that Kamala Harris would be a far better steward of our economy than Donald Trump and we support her candidacy.

Ok. Let’s hear the argument.

The details of the presidential candidates’ economic programs are not fully laid out yet, …

Indeed.

… but what they’ve said, combined with what they’ve done in the past, gives us a clear picture of alternative economic visions, policies, and practices.

Agreed! More on this below in Kamala Harris’s own words.

While each of us has different views on the particulars of various economic policies, we believe that, overall, Harris’s economic agenda will improve our nation’s health, investment, sustainability, resilience, employment opportunities, and fairness and be vastly superior to the counterproductive economic agenda of Donald Trump.

“Sustainability, resilience, … fairness” and other meaningless hoo-hah. What’s not to like?

His policies, including high tariffs even on goods from our friends and allies and regressive tax cuts for corporations and individuals, will lead to higher prices, larger deficits, and greater inequality.

Where have these people been the last four years? Let’s print more $trillions just for the fun of it.

Among the most important determinants of economic success are the rule of law and economic and political certainty, and Trump threatens all of these.

Again, where have these people been the last four years? And please don’t provide cover for the lawless regime we’d been living under.

By contrast, Harris has emphasized policies that strengthen the middle class, enhance competition, and promote entrepreneurship. On issue after issue, Harris’s economic agenda will do far more than Donald Trump’s to increase the economic strength and well-being of our nation and its people.

If only the Biden-Harris had been committed to strengthening the middle class, etc., they might have won the election.

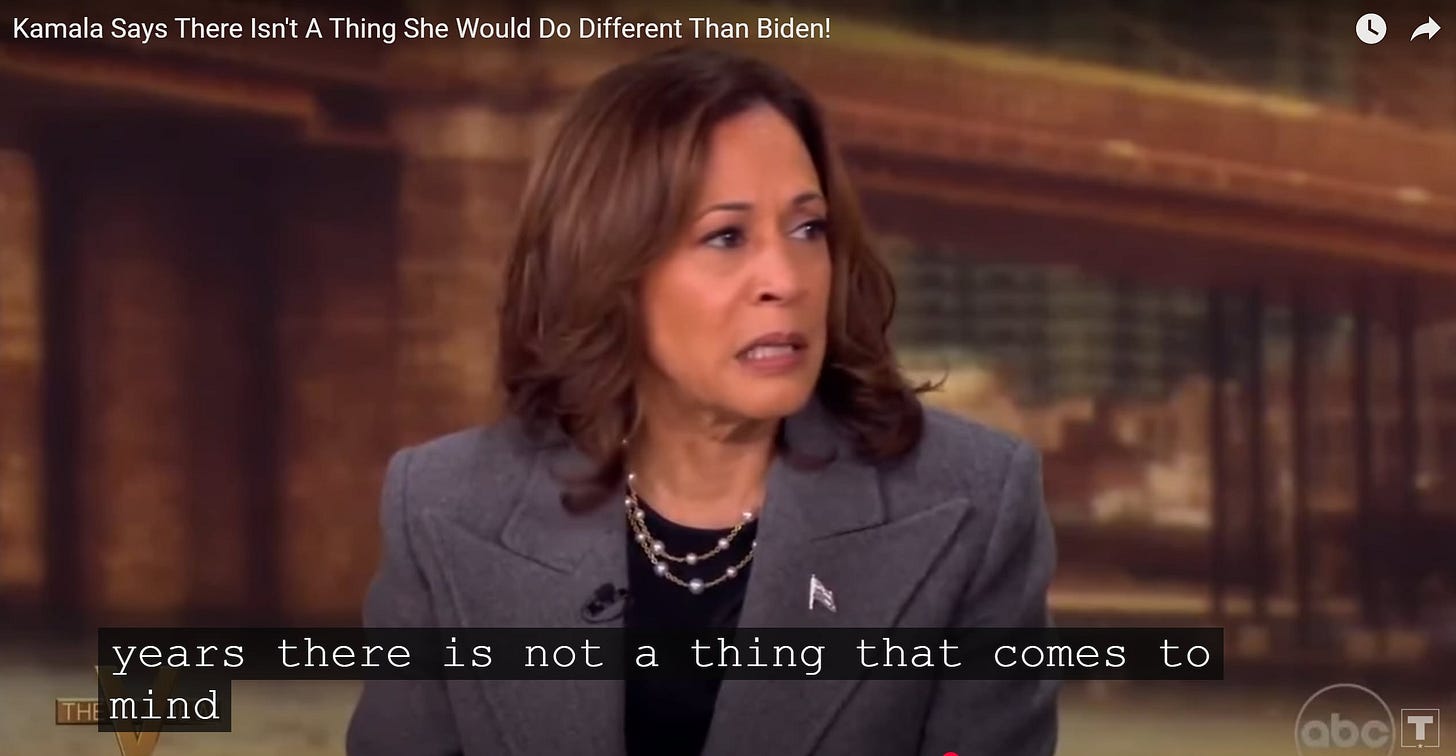

Meanwhile, Kamala Harris could not identify a single policy initiative that she would pursue other than to keep on doing whatever it was that the Biden-Harris administration had been doing. Here she was observing just that on The View:

Dear 23 Nobel Laureates in economics. Your appeal to your own authority was “cringe” and vacuous. If you don’t have anything productive to say, then please don’t say anything.