Failing Upwards with Jeffrey Sachs

More unwitting mis-adventures in politically-correct policy design.

1990. The Russians call in The Fixer. Jeff Sachs had just fixed Poland. The Russians call in Jeff Sachs to fix Russia. Absent a fix, the Russian economy would collapse. But fixing Russia would require the active participation of the United States. Specifically, the United States would have to assemble something of a “Marshall Plan” for Russia. And, yet, the leadership in the United States would decline to do this. In fact, the American leadership wanted to enable the collapse of Russia. Thus, “shock therapy” may have worked in Poland, but it did not work in Russia. Russia collapsed, we ended up with Putin, and here we are. That’s Jeff Sachs’s story as of a Tuesday afternoon late in the summer of 2024.

Here’s an alternative story: As the same Jeff Sachs explains, Poland had already “experienced a decade of collapse in the 1980s.” But, with the central government having retreated from the management of everything, there was only one direction for the economy to go: Up. Everyone already had more than a decade to adapt to the reality of collapse. Everyone at an atomistic, decentralized level had developed skills for coping and for trading with each other in formal and informal markets. All they needed was for actual liberalization, the retreat of an overweening central government. The liberalization for which a critical mass of Poles had been protesting since the first Solidarity protests of 1980 had set the stage for recovery.

Maybe ameliorating some of Poland’s debt obligations, as Jeff Sachs had advised, helped things along. Maybe a few other tweaks like “the backing of Poland’s newly convertible currency” with “a $1billion Zloty stabilization fund” also helped. Or, maybe none of these technocratic tweaks and initiatives were pivotal. But, according to The Fixer, Poland entered a robust stage of recovery “[d]espite Poland’s economy having experienced a decade of collapse…”

So, which was it?: Poland’s economy recovered in the 1990’s, because it had already collapsed in the 1980’s, or the economy recovered despite the fact that it had collapsed in the 1980’s? “Because” aligns more with a supply-side narrative. As Chance the Gardiner in Jerzy Kosinki’s Being There (1970) might have put it: “As long as the roots are not severed, [then] … all will be well in the garden.” That is, create an environment conducive to personal initiative, and after individuals expend much blood and sweat in the pursuit of their own interests, the economy will grow. “Despite” aligns with a demand-side, Keynesian narrative: centralized, technocratic government initiatives will set the stage for economic “take-off.”

The Chauncey Gardiner narrative does suggest questions. For example, as of 1990, was Poland better situated to move out from under governance by centralized administrative process, because the population already had largely moved out from under governance by centralized administrative process? Had the Soviets managed to largely insulate Russia from economic collapse as of 1990… and was Russia therefore likely to face a severe (and possibly protracted) downturn before returning to robust growth? Would a Marshall Plan have averted a protracted downturn in Russia? Or would a Marshall Plan have merely forestalled a sharp downturn? Indeed, would paying the Russians off merely have discouraged private parties from making adaptations? Finally, would the “Mafia Capitalism” about which Vaclav Havel complained in To the Castle and Back (2007) have frustrated broad-based growth and broad reform, anyway? Did Poland not also succumb to such Mafia Capitalism?

I don’t know. But neither does Jeff Sachs. Indeed, it is not obvious (to me) that he knows that he doesn’t know. (He does not volunteer the questions. We know that.) Instead, he just presents himself as this sure man of sure and certain plans. Indeed. The plans are there. It’s merely up to the authorities to do things right. And, if they don’t do things right, then “the whole affair would go to the devil.”

Which brings us back (again) to Gary Saul Morson’s essay from 2019 on (1) sure men with sure, certain plans, (2) how the universe plays with these men and their excellent plans, and (3) how some of those men never figure out that they’ve been played. As Tolstoy’s War & Peace begins, “its main hero, Prince Andrei, believes in a science of warfare, which German generals and theoreticians claim to have elaborated.”

Tolstoy allows this purported social science to stand for all others, existing or to come. At the council of war before the Battle of Austerlitz (1805), the Russians and their Austrian allies plan their campaign according to their supposed science and are certain that “every contingency has been foreseen.” They suffer a disastrous defeat.

This defeat does not in the least shake the generals’ confidence in their “science,” much as … the many failures of contemporary economists’ predictions have never made them less confident of their “science.” Tolstoy loves to show how many ways there are to ignore inconvenient facts. Some of the generals (and some economists) adjust their theories so that they fit what they had failed to foresee, as if the test of a theory were not the ability to predict but to retrodict the known past…

The German generals typically choose another common approach to disconfirming evidence by claiming that defeat, far from invalidating their science, offers yet another confirmation of it. General Pfühl attributes every loss to the failure to carry out his orders to the letter, and since such precision is never possible in battle, he can always argue that, just as he predicted, “ ‘the whole affair would go to the devil.’ . . . He positively rejoiced in failure, for failures resulting from deviations in practice from the theory only proved to him the accuracy of his theory.” As we would say today, his “science” is “nonfalsifiable.”

By contrast, Prince Andrei, a person of absolute intellectual integrity, does learn from disconfirmation. When he enters the army, he attributes Napoleon’s success to two factors—his mastery of military science and his great physical courage under fire. Justly confident of his own courage and intellect, Andrei dreams of becoming the Napoleon who conquers Napoleon. Austerlitz teaches him that, whatever accounts for Napoleon’s success, it is not some purported military science.

As of 2008, Jeff Sachs had not experienced something in the spirit of a post-Austerlitz epiphany. Rather, believing himself as having fixed Poland and blaming his failure to fix Russia on the failure of others to carry out his orders to the letter, Sachs went on to concentrate his energies of fixing Poverty. All of it. Globally. He just needed the chance to prove the concept.

He laid that concept out in The End of Poverty (2005)—that is my understanding, although my own, used copy of the book is only now in the mail. That concept got to see its test in the “Millennium Villages Project.” As Vanity Fair reported breathlessly in 2007 in a piece titled “Jeffrey Sachs's $200 Billion Dream,” George Soros himself contributed $50 million to the project.

Jeffrey Sachs—visionary economist, savior of Bolivia, Poland, and other struggling nations, adviser to the U.N. and movie stars—won't settle for less than the global eradication of extreme poverty. And he hasn't got a second to waste.

Bonfire of the Vanities, really, with Sachs led arm-in-arm by People of the One-name Tribe—Bono and Madonna in this case. Angelina Jolie, when she was still immersed in her Brangelina phase, piped in enthusiastically in her UN role as a goodwill ambassador.

Sachs and his people marketed the project by posing a very good question. Look at all of the wealth in the world. There is more than enough to pay for targeted “interventions” in, say, African villages. Could not such interventions relieve poverty?

Such interventions would involve paying for “fertilizer and high-yield seeds, clean water, rudimentary health care, basic education, mosquito bed nets, and a communication link to the outside world.” "The basic truth is that for less than a percent of the income of the rich world nobody has to die of poverty on the planet. That's really a powerful truth."

Sachs and his people will not have been the first to suggest that the world is capable of producing more than enough wealth to lift everyone out of “poverty.” I frequently cite passages from such sources as Lenin’s State and Revolution (1917) to make the point. Lenin observed that capitalism had demonstrated its capacity to generate fabulous wealth and abundance. We just need to make the system share that abundance more equitably. Easy. John Kenneth Galbraith observed much the same in his two companion pieces The Affluent Society (1958) and The New Industrial State (1967): Our ostensibly capitalistic system actually involved quite a lot of centralized, administrative control, and most of that administration was tied up in large, vertically-integrated corporations. These entities and the system had demonstrated their capacity to generate fabulous wealth and abundance. We should thus give up on our religious orthodoxy of relying on “markets” to deliver us from poverty but rather should allow big government and big business to organize the bigger business of generating wealth. Think of it as a kind of soft Sovietization of everything. Galbraith even compared our “American system” to the actually Soviet system.

The Soviet system collapsed by 1991, and the former Soviets called in The Fixer, Jeff Sachs, to fix it.

Jeff Sachs seems to have acknowledged that the Millennium Villages Project had not yielded proof-of-concept. But “the lessons learned from the MVP are highly pertinent.” Alas, the universe mocks us again.

Meanwhile …

A government policy time bomb set in 1977 blew up the global economy in 2008

Jeff Sachs ventured onto the alternative media circuit this last week, starting with a long discussion with Tucker Carlson. A comment Sachs had made on Tucker’s program—or, rather, an extended conceit he developed—was the initial inspiration for this short essay. In that discussion, Sachs blamed then-Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson for causing the 2008 financial crisis. Or, at least, a casual listener could interpret his comments that way.

Blaming Hank Paulson for crashing the economy in 2008 seems like an uninteresting exercise in connect-the-dots determinism. The story is that the federal government declined to bail-out the investment bank Lehman Brothers. Lehman Brothers was “too big to fail.” Allowing it to fail induced a financial panic. This was unnecessary and avoidable.

Alas, there is more to the story, and it is much more interesting and important than “panic” alone would suggest. Lehman Brothers had gotten so stoked up with “mortgage-backed securities” that were mostly backed up with portfolios of “subprime loans.” Subprime loans are home loans to people to whom banks really shouldn’t be advancing loans in the first place, but, since the late 1970’s, the federal government had been pressuring banks to advance loans to people who really were more likely than other prospective lenders to default on their loan obligations.

One can imagine that banks would not have been too happy to be forced to lend money to high-risk borrowers. If there were money to made lending to such people, the banks would have done it. But, they didn’t. They’d have to be forced to do it.

I would be willing to bet that further research on how banks adapted to pressure to advance “subprime loans” would show that banks did, in fact, come up with some clever adaptations. Most notably, the entire mortgage lending system might have to bear the higher risks that come with supporting subprime loans, but it would make up some of the costs by advancing loans with much shorter terms. Shorter-term loans would induce greater churn in the refinancing of loans. Greater churn generates more refinancing fees. So, in place of offering a subprime borrower a traditional 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, the bank might offer a 5-year or 7-year “balloon” loan. The loan might start out with a very low rate, but, at the termination of the initial term, the rate would “balloon” to a much higher rate. The borrower would thus get stuck with a much, much higher monthly payment. But most borrowers would not actually end up paying those higher payments at those higher rates. Instead, the prospect of having to cover much higher monthly payments would encourage these same borrowers to refinance their loans. So, they might end up with a new short-term balloon loan. That would afford them another 5 to 7 years of low payments after which they end up selling their house or refinancing again. The only catch is that the banking system does collect its fixed fees every time a borrower refinances. Those fees might total many thousands of dollars, but those fees get “financed” by rolling them into the new balloon loan, so the borrower never really feels the sting. In this way, subprime borrowers get access to low rates and low monthly payments, and the banking system gets to extract a higher stream of fixed refinancing fees. Borrowers ostensibly get to own their own homes, but I think it can be useful to understand these borrowers as really just renting their homes from the bank.

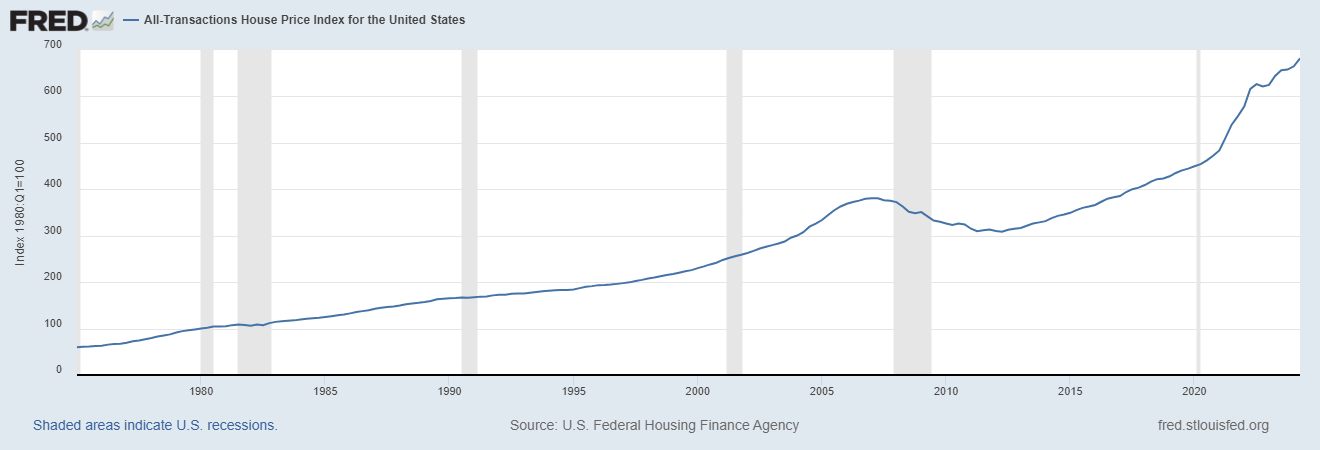

Again, it is not obvious that the banking system performs better by playing this game of combining artificially low rates with churn, but encouraging churn would enable the banking system to take some of the sting out of being forced to advance otherwise unprofitable portfolios of subprime loans. And, the system works so long as housing prices continue, on average, to increase. Why? Because, so long as prices are increasing, subprime borrowers can refinance their loans when it comes time to refinance. But, what if the value of a particular borrower’s house decreases sharply? Under the terms of the prevailing balloon loan, the borrower might owe the bank more money than the house is currently worth. The bank might not be willing to advance a new loan that would enable the borrower to refinance the entire principal that the borrower still owes the bank. The borrower thus ends up with three options: (1) borrow a smaller amount under the terms of the new loan and somehow cover the difference owed under the terms of the current loan and the new loan; (2) allow the current balloon loan to go into its balloon phase and thus end up paying much higher monthly payments; (3) default.

What happens, however, when we get a sharp, market-wide decline in housing prices? The basic idea of “mortgage-backed securities” is that some volume a mortgage loans in a given portfolio of loans will go bad. That always happens. But the going-bad phenomenon will be very idiosyncratic. A random loan here and a random loan there will go bad, but overall, the portfolio of loans should perform well enough. But, when going bad becomes a broad, system-wide phenomenon, the system collapses. That’s what started happening in …. 2007 well more than a year before Lehman Brothers went bust.

Consider the following graphs from our friends at FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data) hosted by the US Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The first graph features “All-transactions House Price Index for the United States” from 1975 through 2024. The second graph zooms in on 1994-2014.

Jeff Sachs’s story is basically that Lehman Brothers was “too big to fail” and that the federal government could have stepped in and saved Lehman Brothers. Saving Lehman Brothers would have averted “the financial crisis.” That’s kind of like saying that the assassination of Archduke Franz-Ferdinand caused the First World War.

Here’s an alternative narrative. It is easy to look back and see that housing markets system-wide had already been in sharp decline starting in 2007. Financial institutions like Lehman Brothers were already under severe stress before Hank Paulson and the Treasury Department decided not to bail out Lehman Brothers. And the underlying problem was that subprime borrowers were choosing to default en masse as their balloon loans would come up for refinancing.

I would suggest that all was not well in the garden long, long before Hank Paulson ever became Secretary of the Treasury. The statutory foundation for forced, system-wide subprime lending goes back to at least the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977. From the New York Federal Reserve Bank:

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was enacted to encourage banks to meet the credit needs of the neighborhoods in which they operate, including low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities. The CRA was enacted by Congress in 1977 (12 U.S.C. 2901) and is implemented by Regulation BB (12 CFR 228). The regulation was substantially revised in May 1995 and in August 2005.

And then this:

The immediate impact of the CRA was to contribute to pressure on lenders to assess the credit needs of low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities in a serious manner…

Indeed. It all sounds so great, but, alas, it looks like the manipulation of markets on the part of the central authorities to achieve nice-sounding but ultimately-fuzzy objectives do not appear to have worked out. Although it did take decades for the some of the worst effects to obtain. And, yet, it is still not obvious that the real problem here was some decision Hank Paulson did or did not make but rather the fact that we have instituted and operationalized deeply flawed policy. And we still don’t know it. Jeff Sachs doesn’t know it.

So, why did the entire house of cards of federalized mortgage financing start to collapse in 2007? Why not 2006? Or 1980? We can always connect dots, but maybe connecting dots doesn’t really reveal much. The exercise might reveal the fact that regulations like those that proceeded from the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 did get a good start in the 1970s … and 1960s. But, the Reagan Administration (1981-1988) really did stem the expansion of such regulations. Not so the administrations of George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush. These three administrations pushed along all types of federal initiatives, including initiatives designed to force banks to advance subprime loans. We want to promote “an ownership society,” they said. “When people own homes in the own communities, they become more engaged with their communities.” And, maybe that’s right. But the financing of “the ownership society” was not organic. All was not well in the garden, and the garden ultimately withered and died, notwithstanding the fact that the federal government forced lenders to pour $trillions into supporting it.

It is too bad that Tucker did not have the presence of mind to press Jeff Sachs on what he meant by arguing that Hank Paulson had caused the 2008 financial crisis. I can imagine that Jeff Sachs would have ultimately offered a much more nuanced and interesting interpretation. And maybe he would have made contact with much more fundamental “root causes” like the flawed statutory foundation of forced lending.

Or not. If I have a problem with Jeff Sachs, it is that he merely advances these single narratives, all of which are variations on Keynesian, technocratic tinkering presented as the one and only orthodox (“right way”) of doing things. He does not take the time to lay out the big questions and to identify sources of uncertainty. It makes for unengaging and uninteresting copy.