Last week I posted a piece titled “A Symbiosis of Honor and Victim Cultures.” That brought some data to bear on the proposition that “honor culture” goes a long way toward motivating much, if not most, homicide in United States. The data included some very high-level FBI statistics as well as some observations from my five-week experience on a grand jury. That jury explored aspects of as many as 80 cases in Washington, DC during one long, typically hot summer.

In this essay I extract some results from a dataset of homicides in Chicago. The Chicago Sun Times has been making an effort to document every homicide in Chicago from the beginning of 2018 to the present.

Since posting the earlier essay, I’ve gotten my hands on Latzer, Barry, The Roots of Violent Crime in America: From the Gilded Age through the Great Depression (2021). Latzer does what I had hoped he would do: review data on violent crime, to the extent any reliable data exist, going back before great waves of internal migration and external immigration took people from the fields to the industrializing cities. More generally, Latzer and the other researchers he cites give some perspective on the motivations for violent crime in America well before the FBI started to systematically record crime data.

Latzer recounts scenes and data from the 1930’s or 1890’s that could just have well come out of the grand jury proceedings. Latzer’s accounts and those proceedings read much like this piece that I read this morning:

On Monday, a 23-year-old in Brooklyn was shot, perhaps fatally, over cold French fries.

It began when Lisa Fulmore called her 20-year-old son, Michael Morgan—who has been charged with attempted murder and possession of a deadly weapon—to fume that McDonald’s workers were being disrespectful toward her over her complaints about cold fries. “I was on the phone with my son. I was like, ‘They in this McDonald’s playing with me,’” she said. Morgan then arrived and, after an argument with a McDonald’s employee, allegedly shot him in the neck and ran off… Did his mother disapprove of his actions? “My son is just saying that he gotta do what he gotta do and the [victim] came after him and whatever happened, happened.”

This absurd pretext for life-taking has chilling echoes of the incident that led to the alleged killing of Austin Simon last month by the now-famous bodega employee Jose Alba. Simon’s girlfriend summoned him to the bodega after Alba rejected her non-functional EBT card and took unpurchased snacks back from the ten-year-old daughter she shares with Simon. “I’m gonna bring my nigga down here, and he gonna fuck you up. My nigga is gonna come down here right now and fuck you up!” she cried before allegedly calling Simon to the utterly unnecessary altercation that ended in his death.

Another instance of fast food-related violence, albeit not deadly, erupted last month when three women in their twenties were filmed ransacking a French fry joint on Manhattan’s Lower East Side—after being asked to pay $1.75 for extra dipping sauce. They gleefully caused $25,000 in property damages and pelted employees with glass bottles and furniture. One worker, Maria Baez, required a staple in her head following the melee.

This comes from Hannah E. Myers, “New York City’s Growing Behavior Gap,” in the City Journal, August 3, 2022. The author goes on to ask, “What has changed such mundane interactions to make them suddenly so fraught with the potential for violence?” The author advances her answer in the subtitle: “The removal of swift consequences for criminal behavior has led to an explosion of violence for even trivial slights.”

The proposition implies, of course, that the potential for violence in response to trivial slights had already been in place. The “root cause” is not a lack of police enforcement but rather something that looks a lot like “honor culture,” centuries old norms that elevate perceived slights into affairs demanding physical retaliation.

Latzer assigns a great role for such norms in The Roots of Violent Crime in America, and he builds on a century of research that does much the same. Long story short: the usual suspects imported into America their cultures of feuds, vendettas, and clan wars from southern Italy, Ireland and the Anglo-Celtic borderlands. As the Italians and the Irish made it into the American main stream and middle class, they largely shed the business of killing over petty matters. Nonetheless, these kinds of things exhibited more persistence in the isolated and insular “South” before the Second World War, but it had been mostly a lower class or upper class, but not middle class, “Scotch-Irish” white thing. It started to become a (lower class) black thing with the first generation after the Civil War that had had no experience with slavery.

With industrialization (mostly in the North) and the exponential decay of the agricultural economy (in the South), especially after the First World War, migrants out of the South, both black and white, exported their culture of violence to the cities in the North. That violence had been mostly concentrated within social networks, and, insofar as those networks were largely segregated by race, then that violence mostly involved black-on-black or white-on-white crime among people who knew each other. The North did not maintain this same tradition of intra-network violence. Rather, the much smaller volume of violent crime in the North involved crimes of opportunity between unaffiliated parties.

All of that makes for a compelling, if not ambitious, narrative, and the narrative helps motivate more questions. Why has such a culture of honor and its attending, deleterious effects, persisted in certain communities but not others?

My own running view of such things is that the incredible volumes of violence remain concentrated in small, urban enclaves. These enclaves might appear to be “marginalized,” but most of the people who live in these enclaves have access to non-trivial streams of income. Those streams might be illicit (drug trade) or public (abundant federal and municipal programs), and many people in these enclaves do have regular, well-compensated employment in bloated city bureaucracies. (Marion Barry’s government in Washington, DC in the 1980’s would be a prime example of how to create an ersatz “middle class” by granting one’s voting constituents employment en masse in an expanded city bureaucracy.) But, the same volumes of violence do not persist in other marginalized communities that also depend on illicit receipts from drugs (from “meth” and opioids) and public proceeds. Think rural West Virginia. Or, perhaps such communities also generate a lot violent crime. But, we don’t hear about it. We do hear a lot about opioid fatalities.

All of that makes for yet another ambitious narrative, but here I am just going to observe that homicide in Chicago has been a shockingly, very black thing (since at least 2018). (Shocking to me, anyway.) The appeal to “ambitious narratives” is just a courteous way of saying that sorting out the how, the why and the persistence of it remains a puzzle, and that’s before we get around to inquiring about candidate remedies. But, here goes:

The stacked bars (blue and yellow) indicate the total number of homicides in a given month. The yellow indicates the number of black homicide victims. The blue indicates non-black homicide victims. Again, my data source is the Chicago Sun Times at https://graphics.suntimes.com/homicides/

I will extract the following results from this graph:

Note the obvious seasonality of homicides. They peak in the warmest months (usually July).

One can distinguish a “George Floyd effect.” Recall, George Floyd died in late May 2020 through the course of a protracted, fraught process on the part of the police to apprehend him and put him in a police car. George Floyd’s death amounted to the proximate cause for months of rioting and arson across many (but not all) American cities.

Seasonality is concentrated in the black homicides.

To the extent that non-black homicides exhibited any seasonality pre-George Floyd, it exhibited peaks in the colder months and diminished during the warmer months. But, post-George Floyd, non-black homicides exhibit something of a phase shift in that they shift to a seasonality that parallels that of black homicides.

Total homicides exhibited a monthly average baseline a little under 50 per month pre-George Floyd but bumped up immediately to about 75 per month post-George Floyd. That makes for an increase in excess of 50%.

Non-black homicides exhibited a monthly average baseline just under 10 per month pre-George Floyd but bumped up to nearly 15 per month post-George Floyd. They also increased about 50%.

The ratio of black to non-black homicides did not really change post-George Floyd, but blacks account for a staggering number of all of those fatalities notwithstanding the fact that blacks account for less than 29% of the population of Chicago as of the 2020 census. Pre and post-George Floyd, blacks accounted for 80.7% and 79.1% of all homicides, respectively. Non-blacks accounted for 19.3% and 20.9% of all homicides.

Why the seasonality? It could just have well come out of stories from the grand jury experience. People start drinking and partying on a Friday or Saturday during the warmer months of the year. They start gathering in a back alley. The party might spill out onto the street. Later in the evening someone chooses to take offense at a jibe. That someone pulls out a gun and retaliates. Bystanders might get hit, but, in any case, there are a lot of witnesses. A lot of witnesses—hence a lot of work for a grand jury to do.

The experience might as well have been drawn out of the 1930’s. Cue Barry Latzer:

Inevitably there were quarrels, usually involving sexual jealousy or gambling disputes. Even the slightest offense could trigger a fight, culminating in a stabbing or shooting. Fox Butterfield told how one man killed another at a supper over some utterly trivial disagreement. “William Bosket’s son, Mamon, killed a man named George Dozier over a bet of ten cents in a game of skin [a popular card game]… Dozier had refused to pay up and then challenged Mamon, saying, I’m not scared of you.’ Mamon pulled his pistol and shot him.”

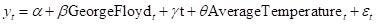

I get results by regressing monthly homicides on a time trend, a George Floyd dummy variable (a binary variable valued at zero pre-George Floyd and at one post-George Floyd), and a sine wave. Specifically, I run a non-linear regression of the following form:

The y term indicates the number of (monthly) homicides. The first instance of the George Floyd dummy variable accommodates the prospect that the George Floyd effect included a discrete, one-time elevation of the number of monthly homicides. The second instance accommodates the prospect that “George Floyd” induced an increase in the amplitude of the seasonal effect. That seasonal effect is modeled by a sine wave. The third instance accommodates the prospect that “George Floyd” induced a phase shift in the sine wave.

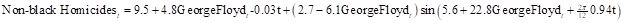

To give both myself and the reader confidence that the sine wave exercise is not over-engineered, I also estimate a simple linear regression of the following form:

In this regression, the Average Temperature (measured at Midway Airport in Chicago) does the work of the sine wave in the non-linear regression.

All of the qualitative results that I report correspond to coefficient estimates that are abundantly statistically significant. The 55 months of data yield surprisingly robust results. Among other things, we find that a George Floyd effect does show up significantly in the beta and lambda coefficients. Specifically, one can distinguish a one-time boost in monthly homicides post-George Floyd as well as a phase shift when it comes to non-black homicides.

In this graph I include predicted values from the non-linear and linear regressions. The red line indicates predicted total homicides (by month) from the linear regression (the regression that features average monthly temperatures). The green line indicates predicted total homicides from the non-linear regression. The blue line indicates predicated “non-black” homicides from a non-linear regression.

Here are the coefficient estimates.

Green line:

Red line:

Blue line:

The red and green lines follow parallel paths, although the green line (the non-linear fit) indicates a better fit to the data. Both the red and green lines yield parallel results. Specifically, total homicides bump up 28.9/32.6 (green/red) homicides per month starting in May 2020. There is no discernible phase shift, but the amplitude of the seasonal effect nearly doubles. The seasonal lows are higher post-George Floyd than the seasonal lows pre-George Floyd, but the seasonal highs post-George Floyd are so much higher that, all together, the low-to-high range is higher post-George Floyd.

Meanwhile, there is statistically distinguishable counter-seasonality in non-black deaths pre-George Floyd, but there is also a conspicuous phase shift post-George Floyd. Specifically, the seasonality of non-black homicides starts to parallel the seasonality of black homicides post-George Floyd.

Why the phase shift and uptick in non-black homicides? Hard to know without knowing more about the relationships of the victims and perpetrators, but one can pose an ominous hypothesis: The people who had concentrated violence during the warmer months in their own social networks had started post-George Floyd to share some of that violence with people outside of their social networks. Homicide may still be concentrated overwhelmingly among people who know each other, but, post-George Floyd there is a modest but statistically distinguishable increase in the volume of violence inflicted on unwitting strangers who had been just minding their own business. Chicago has become a more dangerous place not just in the always violent enclaves but also on Michigan Avenue, uptown in the Lincoln Park neighborhood, and anywhere else.

It would have been great if the data from the Chicago Sun Times had extended many more years back. We might then look for a Soros effect. Much news makes much of the fact that the Soros Open Society Foundation has funded the election campaigns of district attorneys across decades of American cities. Foundation candidates who secured election committed to “restorative justice” as a way of redressing the “disparate impact” of policies influencing law enforcement. Enforcement in Chicago has been under the sway of one such district attorney, Kim Foxx, since 2016. Ms. Foxx secured re-election in 2020 notwithstanding the fact that George Floyd effects had already started to conspicuously kick in. Our statistical results show that homicide rates have increased more than 50% post-George Floyd, but had they also increased appreciably post-2016? If so, that would constitute evidence consistent with a “restorative justice” effect. But, I will have to dig around more (preferably for more monthly data from Chicago) to explore such an effect.

A good source for homicides is the CDC's WONDER database on mortality.

You can't break out the city of Chicago, but you can look up Cook County. It reports the numbers of victims by race by month back to 1999 and by week since 2018.

Thanks for this article. I assume that black homicide is where the perpetrator is black but the victim may be white or black?

Just reading a book called "Why most things fail" by Paul Ormerod who is also an economist. He describes how, despite money being poured into various social programs, the poor and disadvantaged remain poor and disadvantaged and that they remain in tight enclaves (if that's the right word.)