Inflation, Deflation and Les Miserables

A cunning plan: Inflation enables governments to socialize the costs of their programs and to avoid political oversight, all the while immiserating the people least well situated to deal with it.

As a very young fellow, I had been struck by how Jean Valjeant, the protagonist of Les Miserables, made a business of burying fabulous volumes of cash in the forest. This was an important plot point. In times of crisis, Jean Valjeant could disappear into the forest and return, undetected, with quick and easy solutions to impending crises: cash, and lots of it. And, in 1840’s France, there were abundant crises.

More striking was the fact that Jean Valjeant ended up doing two tortuous terms on the prison barges (outside Toulon) and yet had still emerged from the barges equipped to make a fabulous fortune. Just like that. One does have to invest in some volume of willful disbelief to make the story work.

Almost as striking is the fact that everyone in 1840’s France was running around with identity papers. One couldn’t just show up in some town or village, get a job, and get on with the day-to-day. Neither could one just disappear—not without great effort. The authorities wanted to monitor the comings and goings. So, the fact that Jean Valjeant did show up in some town or other, reinvent himself and make a fabulous fortune makes for an ambitious story.

It is no accident that Les Miserables reaches its climax in 1848. The “1848 Revolutions” (plural) spanned the Continent. “Aux barricades!” in 1848. To the barricades again in 1870 with the Paris Commune that succeeded France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. “Aux barricades” may have degenerated into the unwitting self-parody of the self-serious, upper class Soixante-Huitards in1968. But, in 1848, things were rough everywhere, not just France.

The how and why of it is not something I can address right now off the top of my head, but there were hints of what was coming—a decade of global depression—in the financial “Panic of 1837” in the United States. If I recall correctly, Karl Marx understood that the “Panic” and the ensuing economic depression illuminated the first hints of the (Marxist, Hegelian, Progressive and) historically inexorable “Ultimate Crisis of Capitalism.” Marx would have been a randy, privileged nineteen-year-old in 1837, chasing girls and drinking his way through his angry-young-man phase. But the worldly, wise, wizened, still angry thirty-year-old Marx of 1848 … he had divined the answers.

Why was I puzzled by this idea of burying cash in the forest? It amounted to “hiding cash in a mattress.” Why would anyone do that? I had some understanding—not necessarily correct—that holding on to cash made for a bad investment. Cash in a mattress or buried in the forest was money that was not “working.” It was just sitting there depreciating. Was that not one of the superficial lessons of the Parable of the Talents (Matthew 24:14)?:

For it is if a man, going on a journey, summoned his slaves and entrusted his property to them. To one he gave five talents, to another two, to another one, to each according to his ability. Then he went way.

The one who had received the five talents went off at once and traded with them and made five more talents. In the same way, the one who had the two talents made two more talents. The one who had received the one talent went off and dug a hole in the ground and hid his master’s money. After a long time, the master of those slaves came and settled accounts with them. The who had received the five talents came forward, bringing five more talents, saying, “Master, you handed over to me five talents. See, I have made five more talents. His master said to him, “Well done, good and trustworthy slave. You have been trustworthy in a few things. I will put you in charge of many things. Enter into the joy of your master.” And the one with two talents also came forward saying, “Master, you handed over to me two talents. So, I have made two more talents.” His master said to him, “Well done, good and trustworthy slave. You have been trustworthy in a few things. I will put you in charge of many things. Enter in the joy of your master.” Then the one who had received the one talent also came forward saying, “Master, I knew that you were a harsh man, reaping where you did not sow and gathering where you did not scatter seed. So, I was afraid, and I went and hid your talent in the ground. Here you have what is yours.” But his master replied, “You wicked and lazy slave! You know, did you, that I reap where I did not sow, and gather where I did not scatter? Then you ought to have invested my money with the bankers, and on my return I would have received what was my own with interest. So, take the talent from him and give it to the one with the ten talents. For to all those who have more will be given, and they will have an abundance. But from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away. As for this worthless slave, throw him into the outer darkness, where, there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

The first time I heard this story, also as a very young fellow, it was framed in the more gentle language of “servants” rather than “slaves.” But, the point remained: The master (the Almighty) had given his … servants (the rest of us) the gift of life. Some people made the most of this gift. Others did not. They wasted the opportunity to make something of themselves. Indeed, that third servant was so unenterprising that he didn’t even manage to passively invest his one talent with a banker so that he might earn some interest. But here’s where I now add a technical point: It could very well be the case that a talent buried in the ground for safe keeping might yet earn a real return. The same goes for Jean Valjeant’s horde of cash. When the money supply is fixed by being pegged to a gold standard, say, then the value of money appreciates in the face of economic growth. There is deflation. Every talent or every dollar or every franc amounts to a claim on a fixed proportion of the economy. As the economy grows, that claim buys more stuff. Money stuffed in a mattress or buried in the forest may be invested as passively as possible, but that investment yet does some “work” in a deflationary environment. But for the years of the Napoleonic Wars, most of the 19th century was deflationary, especially after the American Civil War when economic growth and networking (railroads) really got going.

In an inflationary environment, of course, cash does not do any work. Its value depreciates over time. What to do in the face of inflation?: Own real assets. Own things that tend to hold their value over time. Buy a house. Even better, use other people’s money (get a mortgage loan) to buy a house if you can get lucky and catch a low rate. Avoid depreciating assets like expensive cars.

The kind of person most likely to be harmed by inflation would be a young person who has no capacity to buy a house. Such people may prove to be good candidates for a class of neo-Miserables. This is the kind of person who the self-anointed best-and-brightest in the sphere of the World Economic Forum exclaim will “Own nothing” and yet “Be Happy!” But all is not lost. A young person can start squirreling away money in mutual funds. Mutual funds provide ways of getting hold of appreciating assets, one small share at a time. But that young person would not be situated to get lucky and nab a low-rate mortgage in an otherwise inflationary environment. Indeed, how could that happen? How is it that any lender would offer loans at low rates in the face of actual or incipient inflation? Don’t lenders adjust mortgage rates to account for inflation? They do, but sometimes the authorities engineer strange opportunities. For example, central bankers flooded the global economy with money during the ersatz pandemic. They did not do such things during the actual flu pandemics of the late 1950’s (“the Asian Flu”) and late 1960’s (“the Hong Kong Flu”), but, in 2020, even I managed to nab a 30-year mortgage at a rate below 3%. No surprise, now that incipient inflation has turned into actual inflation, my mortgage lender has called up to inquire about the prospect of refinancing my loan. The selling point would be that I could liberate some of the cash I have tied up in my house. The tradeoff, of course, is that I would have to commit to a higher interest rate. I demurred. I may have money tied up in the house, but so long as housing prices rise with inflation, that money is working hard. The lender, of course, is not too happy to find itself being paid back at a rate that does not allow payment on the mortgage to keep pace with inflation.

Inflation enables the authorities to arrogate power.

In an earlier essay I talked about how, in the 16th century, inflation enabled Spain to arrogate power to itself, mostly at the expense of the expanding Ottoman Empire. Spain achieved this not by some “cunning plan” but more by accident. It had stumbled on new sources of gold in the New World. Spain then flooded the Mediterranean economy with a stream of gold, and with everyone operating on a de facto gold standard, that stream of gold amounted to a steady and robust expansion of the money supply.

“Everyone” included the Ottoman Turks who had been busy nibbling away at Venetian Empire in the Eastern Mediterranean and pushing into Europe itself by way of the Balkans. Everyone experienced persistent inflation. A problem for the Turks, however, was that they did not have access to sources of gold of the their own. They thus had no capacity to expand their share of the money supply. Spain itself will have experienced inflation, but Spain itself could arrogate more buying power vis-à-vis everyone else by virtue of the fact that it was Spanish gold, not Venetian gold or Ottoman gold that was driving the inflation. One could argue that that same inflation blunted the Ottoman advances into Europe. Paying for Ottoman armies and navies became increasingly costly whereas the Spanish were well situated to keep up with their own inflation.

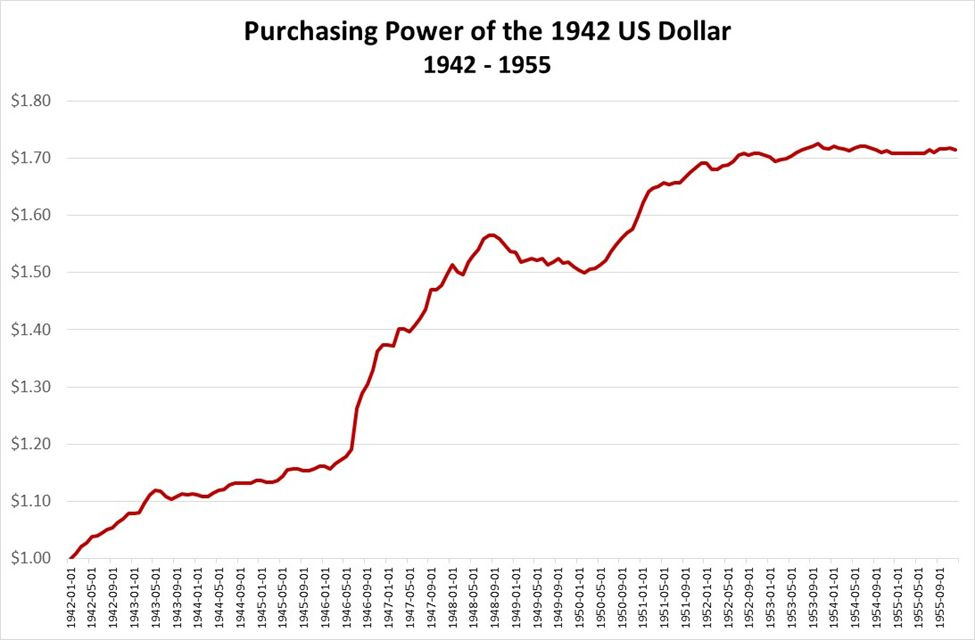

The Spanish Empire of the 16th century has not been the only empire to have benefited from inflation. Inflation has financed American empire since at least the end of the Second World War. Inflation enabled the United States to finance much of its war debt through the 1940’s. All those people who bought war bonds in, say, the beginning of 1942, would have seen their returns eroded by inflation of nearly 7.6% per year from 1942 through 1948; that 1942 dollar could have bought as much as $1.56 in 1948. And, again, that same 1942 dollar maintained the purchasing power of about $1.72 through the early 1950’s. See the following graph.

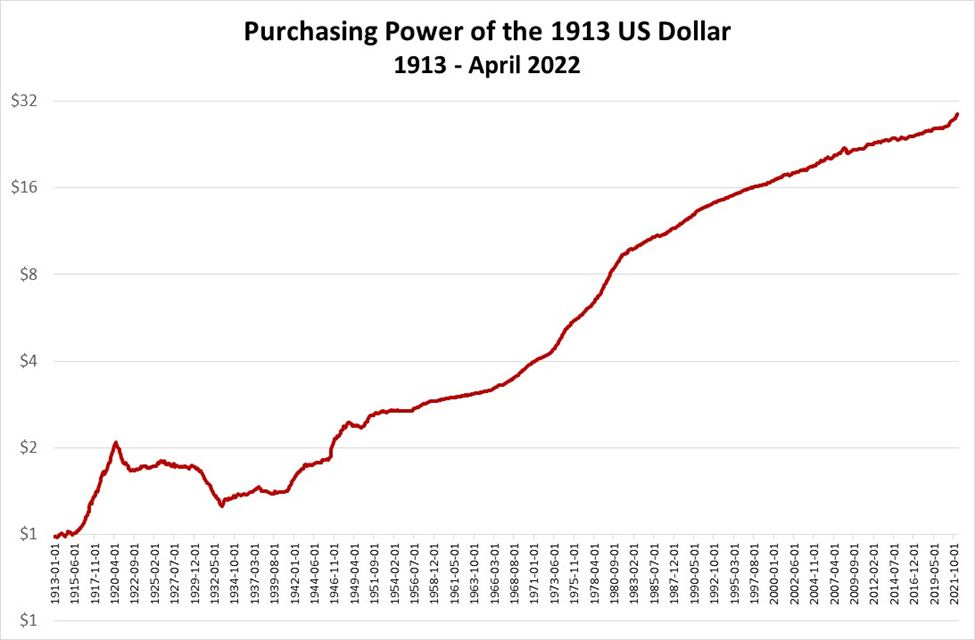

I secured the data for this and other graphs from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CUUR0000SA0R. These data reflect the “Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers.” Such data may under-represent inflation insofar as they do not account for changes consumers make in the typical bundle of consumer goods over time. If, for example, steak becomes really expensive, then consumers may substitute out of steak into cheaper alternatives. Price indices may not adequately reflect such adaptations. That said, here is what the purchasing power of a dollar looked like in 1913, the year before the First World War got going. (The scale of the vertical axis is logarithmic.):

By 1920, more than a year after the end of the First World War, a dollar would have been worth only half as much as it had been worth in 1913. Countries everywhere, led by Great Britain, abandoned a strict gold standard in 1915. Everyone experienced high inflation. In contrast, the value of the dollar was stable through the 1920’s, and it appreciated sharply over the first few years of the Great Depression.

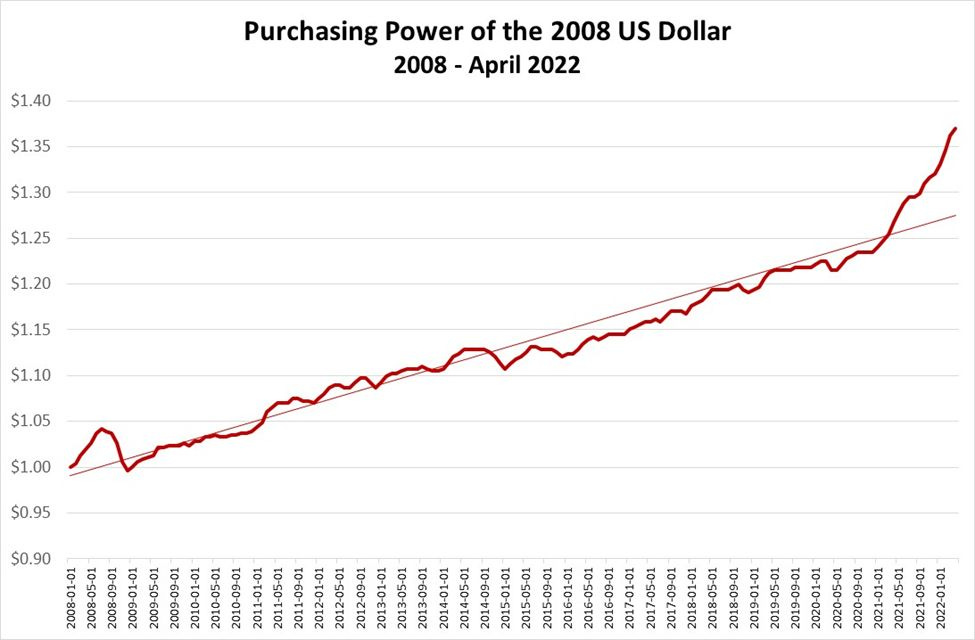

Again, one can see the 1940’s war-time and post-war inflation (1942-1948), and then one can see inflation accelerate through the 1970’s. Inflation does moderate, and one can even discern an episode of deflation in late 2008—that was the “Great Recession”—but one can then see inflation return to a late 1970’s pace over the last two years. To see that more clearly, consider the following graph:

The straight line is a linear trend. A dollar in the beginning of 2008 would have the same purchasing power as $1.24 at the beginning of 2021 just when the Biden administration entered the scene. That amounts to an average, annualized rate of inflation of 1.73% from 2008 through 2020. Meanwhile, that $1.24 in January 2020 supported the same purchasing power as $1.37 in April 2022. That amounts to an annualized rate of inflation of 10.3% over the first 16 months of the Biden term. Compare that to an average annualized rate of 7.48% experienced through the decade of the 1970’s.

Inflation enables Build Back Better by the Back Door.

Why might this matter? It is obvious, isn’t it? Prices are higher. Voters will notice and will wonder what is going on. Prices at the gasoline pump may be most prominent. Other “pocket book” or “kitchen-table issues,” like the costs of groceries, become prominent. But that is not the main point. A bigger point is that the Biden administration is using inflation to encourage demand for its “green” and racialized agenda. The administration has been explicit: If people want to get out from under the burden of paying high fuel costs, then they should shift to alternative, green energy sources. As comedian Stephen Colbert explains, he drives a $100,000 Telsa (an electric vehicle) and therefore does not have to suffer the pain of paying $6-per-gallon gas. What a guy!

There is a yet much bigger point: Inflation enables the Biden administration to socialize the costs of its agenda. “Socialize” is just a pedantic way saying that inflation makes everyone in American society bear the costs of financing the agenda. Through an actually “cunning plan,” the Biden administration, by way of the Federal Government, is doing to American society what the Spanish managed to do to the Ottoman Turks: arrogate more power to itself by vesting itself with a larger share of dollars. There is collateral damage in that vesting the government with more dollars dilutes the purchasing power of dollars in the hands of the public. The dilution manifests itself as inflation; one’s dollars don’t go nearly as far as they used to. The government’s dollars also end up being diluted, but it ends up with a larger share of all dollars and thus arrogates to itself a larger claim on wealth in the economy.

That is not the end of it. Those new dollars amount to new debt, but, when it comes time to service the debt, the government gets away with paying debt holders with depreciated dollars. It gets even worse: The government lends to itself. It does this by “printing money.” The Department of the Treasury may offer bonds to prospective debt holders. We’ve all worried about what would happen if Japanese and Chinese buyers were to stop buying government bonds. The Feds would then have to offer higher interest rates to attract buyers. Higher rates would then increase the burden of servicing the debt. But, enter the Federal Reserve. It can buy the bonds. The Treasury may offer $100 billion in bonds. The Fed can buy the bonds by key stroke, and, just like that, $100 million that had not existed now ends up in the hands of the Treasury. The administrative agencies can then go off and fund whatever projects they want without any oversight. Gender studies programs in Afghanistan? DEI programs in the public schools? No problem.

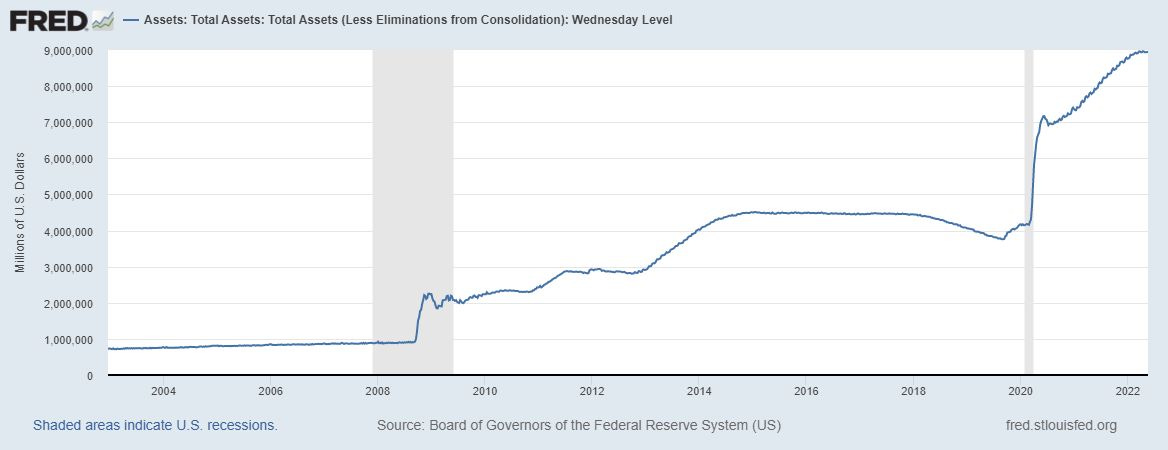

Thus far the Federal Reserve holds about one third of the “public debt”. As the following graph indicates, the Fed made a point of buying a lot of this stuff during the “Great Recession.” It then bought about $3 trillion of this stuff in the wake of the ersatz pandemic. It’s since bought up another $2 trillion.

A $trillion here. A $trillion. So cheap and easy. And, yet, it hasn’t inspired real economic growth. What it has done, however, is relieve any discipline on government spending. Just yesterday the Senate approved $40 billion for Ukraine. (Will this stuff not end up in the pockets of Ukrainian oligarchs?) Then there are other foreign adventures. The United States will be going back to fighting in Somalia, because that’s worked so well over the last 30 years. And then there are the myriad social programs. These include the Biden administration’s program to distribute “Safe Smoking Kits” to drug users. These kits include crack pipes, notwithstanding the fact that the Administration explicitly denied that they included crack pipes. I leave it to the reader to decide whether or not such programs constitute useful applications of funds.

The reality is that the capacity to print money enables the government to fund whatever it wants, much of it absent any political oversight. Administrative agencies can just make it up as they go along. And they do. For example, the effort to secure legislation in support of “Build Back Better” or, the same thing, “The Green New Deal” may have failed, but the government can just go ahead and print money, thereby enabling administrative agencies to pursue a de facto Green New Deal anyway, absent the bit about a “Deal,” because “Deal” implies democratic process. But, democratic process did not support what they wanted to do. So, they simply circumvented democratic process and have gone far toward immiserating the neo-Miserables, young people least capable of dealing with inflation, in order to fund their vanity programs. Will young people go to the barricades, or will they keep voting for their own immiseration?

No surprise it would be to find that depriving the government of the capacity to print money and lend to itself amounts to imposing much discipline on government spending. In the face of severe recession in 1873, the Federal Government found itself having to borrow money from JP Morgan in order to meet its obligations. It could not spend money it did not have by just printing new dollars. The government of late Meiji-era Japan found itself in similar straits. It suffered a sharp decline in revenues during the global depression of the early 1890’s, and it ended up spinning off state-owned enterprises in order to meet its obligations. There was no time or place for vanity programs.

A solid start to a future very long essay - perhaps one of a lifetime. The near magical target of 2% inflation seems to relate to the old US economy. The US tax revenues over a very long time are ~ 20% of GDP. Note that figure is regardless of individual tax rates. The EU is able to extract considerably more in general. The US outlays historically have been ~ 22% of GDP. The deficit (22-20) was ~ 2% so easily covered by mild inflation. That slow grind was tolerable to the public.

Over time outlays have increased with GDP but slowly became heavily oriented toward transfer payments to individuals. Congress ensured it's sinecure by giving favors to we citizens. All that predicted long ago - "When the people discover they can vote themselves the treasury, they will and thus end their great experiment". The financial crisis of 2000 followed by 2008 saw considerable paper wealth simply evaporate. Financial engineering become quite lucrative in the ongoing greed campaign. Sadly a reformer, Mr Obama, arrived as the financial system needed to be 'saved' but at the same time the FDR SS time bomb exploded as we always knew it would.

The deficits of 2008 exploded because none of the remedies to quell the recession improved future growth prospects for real wealth. IMHO financial engineering produces little real wealth particularly if the proceeds are used to fund growth in a corrupt China.

Trump was on a path to try to restore an economy when a disease from China arrived to end his tenure and destroy great chunks of the world economy. Because of the Internet we were able to somewhat tolerate economic cessation unthinkable in the past and the world did so.

Meanwhile, we elected perhaps the most ill suited group of people imaginable to restore the economy. Where this goes is quite unclear as perhaps a near constant future inflation is required to amortize the debt. As service of that debt consumes more of the outlays something must suffer. Whether we will face the reduction of transfer payment is unclear. Worldwide we can expect considerable unrest as previous lifestyles are threatened.

I do hope that the wizards behind the scenes are thinking of solutions. While the WEF pretends a group of billionaires can impose a future, the lessons of the French Revolutions might provide caution.

When a central bank buys government bonds as part of quantitative easing I get the idea that they are trying to push cash into the economy but what does the central bank do with the bonds it has bought? Do they just disappear in a puff of smoke?