Post-war transitions can be more traumatic and more deadly than war itself. Take for example, the confused tangle of armed conflicts packaged up in the crisp label “Russian Civil War” (roughly 1918-1920 depending on what source one reads). Russia may have suffered grievously in the First World War, losing about 1.75 million people. But, the aftermath was worse. Fighting between “Red” and “White” armies; between the new Bolshevik overlords and the peasants in the grain-growing regions of the borderlands; the disruption of agricultural production and (worse) the disruption of logistical networks—that is, the mission-critical business of getting produce from field to table… All of that stuff took a toll in lives lost about twice that of the Great War itself. (I get much of this from one of my favorite sources which I often cite: Conquest, Robert. The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine, 1986.)

That was just Russia. Germany also was in tumult. Ernst Toller, one of the “Two Little Corporals” about whom I have previously written, recounted his experience as an official of the short-lived Soviet Republic of Bavaria. The Bavarian Soviet Republic did not survive fighting with anti-Bolshevik forces, but, before it collapsed, the Russian Bolsheviks had managed to find the time and resources to help their friends in Germany. The cavalry was coming to save the day! At least, that was the plan, and, along the way, Russian forces would dispatch Polish forces that had been wayfaring through western Ukraine. But the Poles managed to surprise the Russians and themselves by sending the Russians into a rout outside of Warsaw. The Russians may otherwise have rolled into Berlin in 1920 rather than 1945.

The Poles were engaged in a lot of fighting in the immediate post-war. Their country had disappeared from the map by 1795 in the denouement of their own fitful, slow-rolling Nakba. But Poland was reconstituted in the redrawing of the map of Central Europe during the proceedings at Versailles in 1919.

Even absent a country for more than a century, Polish identity and institutional capacity had remained strong. This is really quite striking. Note, for example, that the Polish army of 1920 that had routed the Russians was staffed with people who had served with three different armies during the Great War. Many Poles had fought with the Russians, others with the Germans, and yet others with the Austrians, but they all managed to come together and set off on a crusade to seize borderlands that in centuries past had constituted part of Poland’s own Central European empire. That irredentist project eventually fell apart, but the Poles did manage to put up a successful defense of the Versailles Treaty lines of 1919.

The redrawing of lines and the resorting of populations in the aftermath of the First World War may have been ambitious, but it was nothing like the redrawing of lines and resorting of populations that would succeed the Second World War. Poland takes center stage here again. Under the understanding that the “Big Three” (FDR, Stalin and Churchill) committed to at the Yalta Conference (1945), the Soviets would transfer the eastern half of Poland to the SSR’s of Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania. This was much the territory the Soviets had seized from Poland in 1939. Meanwhile, much of eastern Germany would be turned over to Poland.

All of this cutting-and-pasting of maps amounted to shifting the entire state of Poland westward. Implementing this westward shift involved uprooting whole populations in the east and transferring them to the formerly German territories in the west. At the same time, the Soviets turned the Germans out of towns in the west like Breslau and forced them to migrate to a truncated East Germany. Breslau became the Polish city of Wroclaw. In the north, the Hansa port city of Danzig, became Gdańsk once again.

The resorting of peoples on Continental Europe involved the migrations of millions. Those millions will have included much (most?) of European Jewry that had managed to navigate through the deathly hazards of the war. The family of novelist Jerzy Kosinki (the author of Being There, 1971), for example, managed to hide out in a Polish village. The experience informed the crafting of his novel The Painted Bird (1965). Having read the book, I cannot get myself to see the film rendition of 2019. Just when the reader thinks the story can’t get more brutal, it gets more brutal.

How to manage these migrations? The British authorities in the Levant had been frustrating Jewish migration to “Mandatory Palestine,” but, in the immediate post-war, one can imagine pressure to permit heavy migration as a way of dispatching the matter of what to do with the Jews from the whole of Continental Europe. The Zionist project may have stalled in the 1930’s, but now it was game on.

Long story short: A “Plan of Partition” had been floating around since before the war but was now advanced through the new United Nations. Enthusiasm from Jewish factions varied from genuinely enthused to reserved. Arab factions were decidedly unenthused with all of them, including the Arab League, rejecting the deal. (The whole of the Arab world would have a say in this matter?) Fighting had already broken out by the time the British mandate had expired in 1948. (Even I know people who had tales about parents who made careers running guns under the noses of the British in 1947 and 1948.) One thing led to another, and a critical mass of Jewish factions managed to take the initiative and declare a State of Israel. Israel quickly secured recognition from the United States and a host of other countries.

In the made-for-TV version of all of this, the post-war migration amounted to European colonization of Palestine… and the British authorities made a mess of the whole affair. But, then, how was it that the British ended up managing Mandatory Palestine in the first place, and what alternatives had there been to bringing the British in to manage things? What was this “Mandate” business?

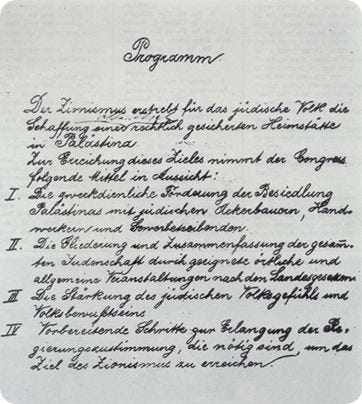

At the very least, the story should be rolled back to the formal beginning of the Zionist project, and it begins with a surprise and a puzzle. The original concept was to find a “homeland for the Jewish people.” A big plot of land in eastern Oregon could just as well have suited the bill. It turns out that the Brits advanced the idea of establishing a homeland somewhere in East Africa. But, when Theodor Herzl set out to raise money for the project, the biggest demand he got was to secure a “homeland in Palestine”. And, so, the First Zionist Congress (in Basel, Switzerland, 1897) put out the “Basel Program” according to which “Zionism seeks to establish a home for the Jewish people in Palestine secured under public law.” (One of my sources about Theodor Herzl’s activities is Barbour, Nevill, Nisi Dominus: A Survey of the Palestine Controversy, 1946.)

The surprise (to me, anyway) was that the debate in the run up to the First Congress did contemplate alternatives to Palestine. The puzzle (in my mind) pertains to this business of securing a homeland “under public law.” Surely, the phrase alludes to the fact that the Palestine of 1897 was (no surprise) already governed by an established authority, the Ottoman Empire… or what was left of it.

“Under public law” anticipates the matter of securing legitimacy for the project. At the very least, the process would have to engage the Ottoman authorities, and, sure enough, Theodor Herzl managed to arrange some correspondence with the Sultan. Herzl himself reports that the Sultan declined to give his imprimatur to the project, but the Sultan also seemed to recognize that Ottoman authority had been deteriorating. Specifically, the Sultan observed that the proponents of the Zionist project might yet be able to secure the homeland “gratis” if they were to wait around long enough.

We can all see that nothing comes for free, but the Sultan was on to something: The hazardous business of redrawing lines, resorting peoples, and reasserting authority may succeed the end of wars, but the disintegration of empires also creates opportunities to redraw lines and assert authority. Admittedly, that may generate demands to impose the migration of peoples. And that may generate great hazards. Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 in the wake of the dissolution of British authority would make for a vivid example. An interesting counter-example might be the peaceful breakup in 1992 of Czechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. That bit of redrawing and resorting, of course, came in the wake of the dissolution of Soviet empire.

The disintegration of authority may also motivate wars. Generally, as imperial authority recedes, other parties fill the void. The hazards include the fact that many competing parties may move to assert competing claims. Hence the sequence of “Balkan Wars” in the run up to the First World War as the authority of both the Ottoman Empire in the south of the Balkans and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the north receded. The leadership of restive populations in the Balkans asserted overlapping claims. The Balkan Wars constituted fighting over those claims.

And what of competing claims and competition in the Arab world? On the Arabian peninsula, the House of Saud managed to expand its authority at the expense of the Ottomans and other Arab factions. The Saudis ultimately managed to consolidate their hold on the peninsula by the early 1930’s.

Then there were competing claims in Palestine. The Mandate for Palestine explicitly contemplated the carving out of a Jewish “national home” in some portion of Palestine as well as an Arab state (Transjordan) east of the Jordan River. As we all know, the partition plan of 1947 made accommodations for Arab communities west of the Jordan, but the various factions could not agree, hence the 1948 war.

* * *

Here are a few questions: Suppose there had been no Mandate for Palestine right after the First World War. Suppose no party—not the Brits, not the French, not anyone—took on the role of imposing some semblance of security in the immediate aftermath of the war. What other powers, great or small, would have swept in to the void left by the departing Ottomans? Would there have been great dislocation, violence and forced migrations? Would Christians, Jews and Muslims have clustered into Christian, Jewish and Muslim enclaves? Would Palestine have turned into something like 1970’s Lebanon? Maybe the Brits did not do such a bad job.

I get the idea of both Palestine and Lebanon prospectively becoming like a fractured and failed Lebanon from sources such as The Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926). In that book, T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”) gives some clues about what the Ottoman Levant looked like while the Ottoman Turks remained nominally in control in 1917.

Lawrence describes a very rough neighborhood and does not have many charitable things to say about anyone in it. Not about Jews, Druse, Shia Muslims, Sunni Muslims, Arabs, Armenians, Greeks, Kurds, Maronite Christians, other Christians, Yazidis … He does make some passing contact with the Zionist project without explicitly identifying it. All of the italics are my own. From Chapter 58:

Our feet were upon [Syria’s] southern boundary. To the east stretched the nomadic desert. To the west Syria was limited by the Mediterranean, from Gaza to Alexandretta. On the north the Turkish populations of Anatolia gave it an end. Within these limits the land was much parcelled up by natural divisions. Of them the first and greatest was longitudinal; the rugged spine of mountains which, from north to south, divided a coast strip from a wide inland plain. These areas had climatic differences so marked that they made two countries, two races almost, with their respective populations. The shore Syrians lived in different houses, fed and worked differently, used an Arabic differing by inflection and in tone from that of the inlanders. They spoke of the interior unwillingly, as of a wild land of blood and terror.

The inland plain was sub-divided geographically into strips by rivers. These valleys were the most stable and prosperous tillages of the country. Their inhabitants reflected them: contrasting, on the desert side, with the strange, shifting populations of the borderland, wavering eastward or westward with the season, living by their wits, wasted by drought and locusts, by Beduin raids; or, if these failed them, by their own incurable blood feuds…

[A] main component of the coast population was the community of Ansariya, those disciples of a cult of fertility, sheer pagan, anti-foreign, distrustful of Islam, drawn at moments towards Christians by common persecution. The sect, vital in itself, was clannish in feeling and politics. One Nosairi would not betray another, and would hardly not betray an unbeliever. Their villages lay in patches down the main hills to the Tripoli gap. They spoke Arabic, but had lived there since the beginning of Greek letters in Syria. Usually they stood aside from affairs, and left the Turkish Government alone in hope of reciprocity. Mixed among the Ansariyeh were colonies of Syrian Christians; …

[I]n the bend of the Orontes had been some firm blocks of Armenians, inimical to Turkey. Inland, near Harim were Druses, Arabic in origin; and some Circassians from the Caucasus. These had their hand against all. North-east of them were Kurds, settlers of some generations back, who were marrying Arabs and adopting their politics. They hated native Christians most; and, after them, they hated Turks and Europeans.

Just beyond the Kurds existed a few Yezidis, Arabic-speaking, but in thought affected by the dualism of Iran, and prone to placate the spirit of evil. Christians, Mohammedans, and Jews, peoples who placed revelation before reason, united to spit upon Yezid…

A section across Syria from sea to desert, a degree further south, began in colonies of Moslem Circassians near the coast. In the new generation they spoke Arabic and were an ingenious race, but quarrelsome, much opposed by their Arab neighbours…

Beyond them were the strange sights of villages of Christian tribal Arabs, under sheikhs. They seemed very sturdy Christians, quite unlike their snivelling brethren in the hills. They lived as the Sunni about them, dressed like them, and were on the best terms with them. East of the Christians lay semi-pastoral Moslem communities; and on the last edge of cultivation, some villages of Ismailia outcasts, in search of the peace men would not grant. Beyond were Beduin.

A third section through Syria, another degree lower, fell between Tripoli and Beyrout. First, near the coast, were Lebanon Christians; for the most part Maronites or Greeks…

On the higher slopes of the hills clustered settlements of Metawala, Shia Mohammedans from Persia generations ago. They were dirty, ignorant, surly and fanatical, refusing to eat or drink with infidels; holding the Sunni as bad as Christians; following only their own priests and notables. Strength of character was their virtue: a rare one in garrulous Syria. Over the hill-crest lay villages of Christian yeomen living in free peace with their Moslem neighbours as though they had never heard the grumbles of Lebanon. East of them were semi-nomad Arab peasantry; and then the open desert.

A fourth section, a degree southward, would have fallen near Acre, where the inhabitants, from the seashore, were first Sunni Arabs, then Druses, then Metawala. On the banks of the Jordan valley lived bitterly-suspicious colonies of Algerian refugees, facing villages of Jews. The Jews were of varied sorts. Some, Hebrew scholars of the traditionalist pattern, had developed a standard and style of living befitting the country: while the later comers, many of whom were German-inspired, had introduced strange manners, and strange crops, and European houses (erected out of charitable funds) into this land of Palestine, which seemed too small and too poor to repay in kind their efforts: but the land tolerated them. Galilee did not show the deep-seated antipathy to its Jewish colonists which was an unlovely feature of the neighbouring Judea.

Across the eastern plains (thick with Arabs) lay a labyrinth of crackled lava, the Leja, where the loose and broken men of Syria had foregathered for unnumbered generations. Their descendants lived there in lawless villages, secure from Turk and Beduin, and worked out their internecine feuds at leisure. South and south-west of them opened the Hauran, a huge fertile land; populous with warlike, self-reliant and prosperous Arab peasantry. East of them were the Druses, heterodox Moslem followers of a mad and dead Sultan of Egypt. They hated Maronites with a bitter hatred; which, when encouraged by the Government and the fanatics of Damascus, found expression in great periodic killings. None the less the Druses were disliked by the Moslem Arabs and despised them in return. They were at feud with the Beduins, and preserved in their mountain a show of the chivalrous semi-feudalism of Lebanon in the days of their autonomous Emirs.

A fifth section in the latitude of Jerusalem would have begun with Germans and with German Jews, speaking German or German-Yiddish, more intractable even than the Jews of the Roman era, unable to endure contact with others not of their race, some of them farmers, most of them shopkeepers, the most foreign, uncharitable part of the whole population of Syria. Around them glowered their enemies, the sullen Palestine peasants, more stupid than the yeomen of North Syria, material as the Egyptians, and bankrupt.

East of them lay the Jordan depth, inhabited by charred serfs; and across it group upon group of self-respecting village Christians who were, after their agricultural co-religionists of the Orontes valley, the least timid examples of our original faith in the country. Among them and east of them were tens of thousands of seminomad Arabs, holding the creed of the desert, living on the fear and bounty of their Christian neighbours. Down this debatable land the Ottoman Government had planted a line of Circassian immigrants from the Russian Caucasus. These held their ground only by the sword and the favour of the Turks, to whom they were, of necessity, devoted.

This was the neighborhood that the Brits volunteered to manage after the withdrawal of the Ottoman Turks. (Imagine getting that assignment.) Lawrence had important experience in the Levant before the war, which is part of the reason the British leadership tapped him to organize the Arab Revolt (on the Arabian peninsula) and to attempt to organize restive populations in the Levant in the subsequent drive to Damascus. Lawrence may have appreciated that governing the region under the terms of the Palestine Mandate would make for a fraught affair, but one can wonder how things would have turned out absent the British Mandate.

* * *

American sponsorship of Israel, as measured by aid, started to pick up in the early 1970’s and really took off after the Yom Kippur War of 1973. Like it or not—and various factions decidedly do not—American sponsorship did deliver a measure of stability to the region. Successive administrations made big efforts to encourage Arab states to formally recognize Israel all as part of a larger effort to resolve the “Palestine controversy.” The first big breakthrough would have been the deal mediated by the Carter administration between Israel and Egypt in 1980. (Hardliners in Egypt assassinated Anwar Sadat in 1982.) Progress stalled after that, and a frustrated US Secretary of State James Baker ultimately declared in 1991 that the United States would suspend efforts to mediate further deals. But then we learned of the Oslo Accords, an initiative mediated by the Norwegians. The Oslo process shifted the focus from deals between Israel and Arab states to the implementation of a “two-state solution.”

There seemed to be some expectation through the Clinton years that the Israelis and Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) could commit to a two-state solution, although the PLO leadership (Yasser Arafat) seemed to be merely going through the motions. It seems that, by the time Israeli premier Ariel Sharon visited the Temple Mount in 2000, much of the Israeli leadership had become frustrated with the lack of progress and gave up on the Oslo process.

The next big innovation in the quest for stability (if not outright peace) came from the government of Ariel Sharon itself: unilateral “disengagement” from Gaza. Factions debate about what “disengagement” entirely means, but it did involve uprooting 21 Israeli settlements from the Gaza Strip and making Gaza something of an autonomous zone under the control of Palestinian authorities.

Interestingly, the Palestinian authorities committed to elections in Gaza and in the West Bank. Hamas handily won the elections in Gaza in 2006… and that was the end of elections in Gaza. That set up the next initiative: a campaign, coordinated with Hezbollah in Lebanon, of launching rockets into Israel. Hamas itself has been periodically launching rockets into Israel ever since. It’s been going on for nearly 20 years.

Hezbollah claimed in 2006 that the purpose of the rocket campaign was to raise the costs on Israelis of living in Israel and to encourage the Israelis to leave. From the Associated Press (July 24, 2006):

“We are going to make Israel not safe for Israelis. There will be no place they are safe,” [Hezbollah's representative in Iran Hossein] Safiadeen told a conference that included the Tehran-based representative of the Palestinian group Hamas and the ambassadors from Lebanon, Syria and the Palestinian Authority…

“We will expand attacks,” he said. “The people who came to Israel, (they) moved there to live, not to die. If we continue to attack, they will leave.”

Big talk, perhaps. Such was my own thinking when I first read this AP piece back in 2006. The ravings of a small cabal of cranks do not make for a sustained campaign. But, it was what happened next that shocked me: The “international community” swept in and condemned the Israelis for retaliating.

The BDS initiative (“Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions”) got rolling at just this time. That was no accident. Hamas also got into the business of periodically shooting rockets into Israel. The combined BDS-and-rockets campaign seems designed to produce this dynamic: shoot rockets, publicize Israeli retaliation, call for BDS. Wash-rinse-repeat.

It was through this experience of shock that I myself lost all confidence in “two-state” initiatives. The critical mass of opinion both in Gaza and the “international community,” I learned, really does favor the BDS-and-rockets campaign. These factions have no interest in anything but the traditional one-state solution: drive the Israelis into the sea.

What to do then? Since 2006, various Likud governments in Israel appear to have committed to a new long game: Start generating “new facts on the ground”—specifically, new settlements on the West Bank and try to contain the hazards generated by Hamas in Gaza. Even so, it wasn’t obvious where the unilateral Israeli process (the business of assembling “new facts”) and the unilateral Hamas campaign (BDS-and-rockets) would go—not until the launch of the Abraham Accords under the Trump administration.

The Abraham process shifted focus away from the “two-state” concept and back to the business of getting Arab states to formally recognize Israel. And, an amazing thing happened: much of the attention that had been lavished on Hamas and the BDS movement dissipated. Everyone had bigger things to talk about. The Abraham process was finessing the entire BDS-and-rockets campaign.

It looked like the “Palestine controversy” might yet be resolved. It would be resolved by “new facts,” although not by new settlement activity, but by Arab states basically giving up on the Palestinian matter.

Obviously, not everyone would be happy with any resolution to the “Palestine controversy” that would leave Israel intact, but a solution seemed to be emerging.

Long story short: The Saudis were preparing to sign on to the program, but Hamas made its big move on October 7 (the October 7 massacres), and that made it too hard for the Saudis to proceed with formal recognition of Israel. One may wonder if the Saudis secretly anticipate the bitter chapter that is the Israel-Gaza war to pass and to eventually get back on the path to formal recognition. But, the immediate result is that the BDS campaign has recaptured the focus of attention.

* * *

In January 2023 I attended an “Antiwar Rally” in Washington, DC. The rally, of course, amounted to a protest of American support for war in Ukraine. The rally attracted a sizable, but not massive, crowd. It did, however, attract a diverse crowd. The Libertarian Party set up a booth. Most of the crowd was composed of the usual “antiwar” suspects: basically Antifa types who may themselves be … who are totalitarians masquerading as freedom-fighting “anti-fascists.”

My guess is that these people largely populate the anti-corporate crowd. They believe in the pre-WWI notion of “Finance Capitalism,” the same stuff of “Bankers’ Wars.” Here the idea is that the bankers—most notably Jewish bankers, the Rothschilds and such—cause wars, because war is good for business. I would suggest that (a) there is a causal relationship between banking and war but that (b) the causality runs from war to banking, not banking to war; Wars cause Banking, Banking does not cause Wars. Basically, people need to finance wars, so, when they go to war, they seek out bankers. It would thus be no accident that, historically, bankers enter the scene when the scene gets hot.

Note, however, that lending to warring parties can make for a fraught financial affair. In 1290 or so, Edward II of England, “the Hammer of the Scots,” cast out the Jews from England. Why? Likely, I confidently guess, because he owed them massive sums for his wars against the Scots.

The Jews of the England were not the only ones who had to put up with the consequences of lending to kings in default. Lending to warring kings and warring Popes had often proved to be ruinous and had taken down any number of Italian banking houses. (On this count, let me suggest Hunt, Edwin, The Medieval Super-Companies, 1994.) Edward II also had a hand in bringing down some number of Italian banking houses.

* * *

I did make a point at the Antiwar Rally of documenting some of the imagery. The imagery included some number of Russian flags, Soviet flags, and rainbow flags. I also saw a red-white-black-and-green flag. What was that? An Iraqi flag, I wondered? Something else?

Something else, indeed. We can now all recognize that flag as a Palestinian flag.

Speakers included people whom I had heard of (Jimmy Dore, for example) as well as folks about whom I had never heard (Jackson Hinkle … that was his name)? But, all of these folks—all of them—have lined up loudly and solidly in a phalanx of Twittering X-ers behind the narrative that “Israel is committing genocide/ethnic cleansing” because, obviously, it wants to absorb the Gaza Strip within its firm control.

No, the Israelis do not want to control Gaza. No one wants to control Gaza. The Israelis want the Palestinians to govern Gaza like adults, and adults do not randomly fling rockets over the border on any given day of any given year, year after year going on 17 years now. The Israelis and all the leadership in the Arab world want the Palestinians to get on with their lives. Nobody wants to take on the burden of governing this restive population.

* * *

Had the morning of Saturday, October 7 had unfolded much like the morning of Saturday, September 30, there would be no war in Gaza. To the good, liberal democrats in the West, it is natural to ask, “Can’t we all just get along?” Can’t we all just commit to liberal democratic process and leave it to that liberal democratic process to sort out our differences going forward?

One reality is that we cannot always commit to liberal democratic process, because minority factions may worry that majority factions will dispense with liberal democratic process once they get in control. Everyone has absorbed the lessons of Weimar Germany in 1932 when one of the “two corporals” managed to secure the chancellorship of Germany. That marked the end of liberal democratic process.

That’s why the dream of a liberal democratic single-state solution remains but a dream and we keep coming back, decade after decade, to the “two-state solution.” And with the Palestinian authorities in both Gaza and the West Bank—Hamas and Fatah, respectively—having demonstrated no interest in elections, who can blame outside observers for being skeptical of the commitment of these same factions to liberal democratic process.

So, here we are. Typically factious, fractious and diverse Israeli opinion may (for now) have become more concentrated, and it is has not become concentrated on the idea of pursuing further dreams of a “two-state solution.” It has become concentrated on destroying the capacity of Hamas to wage its BDS-and-rockets campaign. Blessed we are so far to observe that Hezbollah in the north has not acted more forcefully. What concerns hold them back?