How I learned to stop worrying and to Love Fats and Carbohydrates

The science of nutrition remains shockingly underdeveloped.

Journalist Nina Teicholz got a gig reviewing restaurants in New York. She was happy to get the gig, but, at the same time, she was concerned that regularly eating out at restaurants would mess up her diet. Her diet would deviate from orthodoxy in that she’d end up consuming richer foods and more calories. Those calories would be made up of fats and carbohydrates, just the things anyone interested in remaining trim would want to avoid. Indeed, in place of healthy foods, she could expect to consume heavier, fattier foods—more meat, more cheese and creamy sauces, more of everything that we’re not supposed to eat. She ended up losing ten pounds.

The lesson is not that turning around and eating everything we’re not supposed to eat will induce one to lose ten pounds. Rather, Nina’s body had adapted to a particular diet regimen. That regimen changed. She then lost weight and perceived herself to be healthier. But why? How?

Exploring the how and the why—and taking the time to write it up—motivated Teichholz to compose The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat, and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet (2014). (I subsequently stumbled upon an account of Nina Teicholz’s motivation for writing the book in a vignette tucked away in Michael Shellenbergers’s Apocalypse Never [2020].) The principal conclusion of The Big Fat Surprise might be the idea that there is a place for fats, including animal fats, in a healthy diet. On my reading, however, an equally important result might be that it remains a mystery about what would constitute the ideal diet. Indeed, Nina does not end up advocating for an ideal diet. And that is to her credit, for she learned that “The Science” of nutrition remains remarkably underdeveloped.

I would further suggest that the most important result of the book might be the fact that “The Science” has been much like Soviet Science, of stuff like Lysenkoism, in place of what science should be. “The Science” had become preoccupied with manufacturing orthodoxy by manipulating evidence to fit pre-determined conclusions. Actual science should be about allowing the data to speak for themselves.

The Big Fat Surprise identifies much of the science from which orthodoxy ultimately emerged. Long story short: I understand from various sources that, by the early part of the 20th century, researchers had identified cholesterol as an important suspect in heart disease. Meanwhile, by the early 1950’s some understanding had developed that heart disease was becoming a more prominent phenomenon. Then, in 1955, as if on cue, the American president, Dwight Eisenhower, suffered a “massive” heart attack.[1] Eisenhower’s treatment involved little more than six weeks of bed rest, but it was only a few years before his health had become front-page news that the innovation of gas-liquid chromatography had enabled researchers to start identifying types of fats. Researchers thus found themselves blessed with a new, shiny, powerful toy. The race was then on to identify correlations between types of fats and heart disease. Could researchers ultimately identify causal relationships, and could such relationships inform dietary choices?

Very long story short: Enter Ancel Keys, who would soon come to establish himself as the Anthony Fauci of government-funded and government-sanctioned nutrition science. Saturated fats would be declared as bad. Hydrogenated fats (“trans fats”) would be advanced as good substitutes for other fats. So, for example, people were encouraged to substitute butter with margarine. But, trans fats would later be identified as “killers,” because the settled Science had changed.

One thing the incontrovertible Science did seem more consistent about was the idea that high-fat diets were bad. And cholesterol would remain a culprit, at least in the United States, notwithstanding the fact that the body produces it, the brain needs it, and it is not obvious that a person’s cholesterol levels vary widely with diet. Cholesterol levels between people may vary a lot, but, surprisingly, it is not obvious that diet has a lot to do with it.

European countries have given up on advancing guidance on cholesterol levels, but Americans continue to take their cholesterol-reducing statins. One can only wonder what role that might play in cognitive performance over time. Does depriving the brain of cholesterol promote dementia? Meanwhile, for some decades now, people have also worried about carbohydrates… So, if fats are bad and carbohydrates are bad, then where should people get their calories from? If not from fats or carbohydrates, then they have to get them from proteins. Is this kind of thing part of the motivation for “paleo” diets—that is, we should eat like hunter-gatherers? We should give up on grains (mostly wheat and rice), because the cultivation of grains is what brought the business of hunting and gathering to an end?

Civilization, it turns out, was built on a foundation of carbohydrates: rice in East Asia; wheat in Europe, Asia Minor, and North Africa; potatoes in South America; maize in Central America. Carbohydrates proved to be an efficient source of calories. They put out far more calories than their cultivation required, and, to some observers, this was a bad thing. Cheap calories could support larger populations. (Bad by the estimation of some.) Those populations would trade in their wandering, nomadic lifestyles for life in the civitas—in the city, the thing that makes civilization civilized. (Also bad by the estimation of some.) Those city-dwellers might grow up to be less physically robust than their nomadic cousins. (Also bad.)

One might get the sense that observers like Yuval Hariri, the author of Sapiens (2011), perceive much of what civilization has become as bad, but I leave it to the reader to decide for him or herself whether or not we should condemn carbohydrates and the civilization it enables. Right now, I take up some exploration of the question of whether the industrial production of carbohydrates, including the proliferation of highly refined sugars in the food supply, has contributed to obesity in the United States. I start with one proposition and one empirical observation. First, the concept of the low-carb diet seems to be motivated by this idea that denying oneself access to carbohydrates will induce one’s metabolism to burn fat. This is part of the carbs-are-bad orthodoxy. Second, I note that per capita consumption of wheat in the United States had increased sharply from the late 1970’s to the late 1990’s. Were people consuming more carbohydrates, and was that contributing to the incidence of obesity? And how were those carbohydrates showing up in the food supply? Were people eating more bread and pasta, or were wheat-derived carbohydrates showing up more in processed foods? Were people getting more of their calories from processed foods? Overall, were they consuming more calories?

This last set of questions came to mind when I was working on an antitrust merger investigation involving flour milling. I had assembled data from various sources, including the US Department of Agriculture, and I just happened to notice that per-capita consumption of wheat had increased sharply since the late 1970’s. I also noticed that work force participation had increased in (apparent) lockstep with the increase in wheat consumption. An ambitious narrative then sprang to mind. “Women’s liberation” in the 1970’s was a real thing after all! Women were moving into the work force en masse—hence the rise in the labor force “participation rate”. (I recovered data on labor force participation from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.) People were busier. They had less time to cook nice, balanced meals for themselves. They were more likely to substitute home-cooked meals with convenient, processed foods. And maybe they were also consuming more bread and pasta. Taken all together, did that induce people to put on more weight?

Of course, other things could have been going on. Diets may or may not have been changing, but perhaps moving into the labor force entailed taking on more sedentary lifestyles. Perhaps men in the labor force had already taken on such lifestyles, but women moving in to the labor force were spending more time commuting and working at the office rather than taking up more aerobic pursuits at home. Were pursuits at home more aerobic? What was going on?

I can’t comment on the question of whether a lifestyle organized around office work has tended to be more or less aerobic than a lifestyle organized more centrally around the home, but I will show the reader what I’ve seen in data from the Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

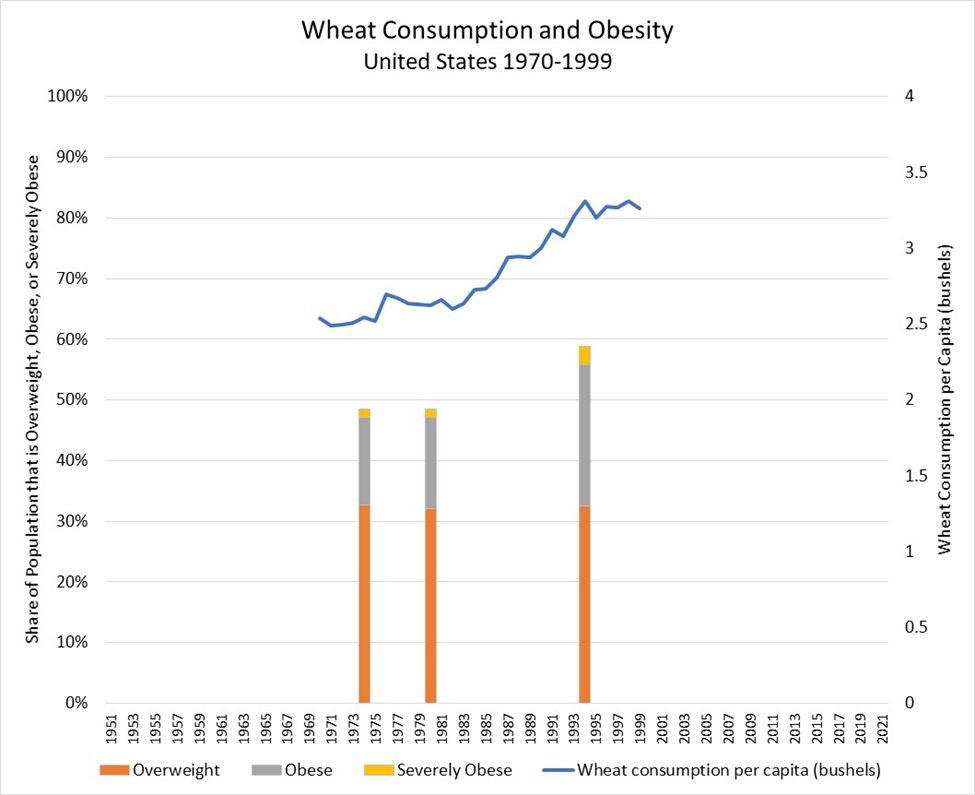

The following graph features annual consumption of wheat per capita (in bushels).[2] I map wheat consumption against the results of three CDC surveys of obesity among adults aged 20-74 in the United States.[3] Adults are indicated as being either not overweight, overweight, obese, or severely obese.

So. Wheat consumption goes up, and the proportion of the adult population (aged 20-74) that is overweight or obese or even severely obese goes up from under 50% to just under 60%. Are carbs the cause?

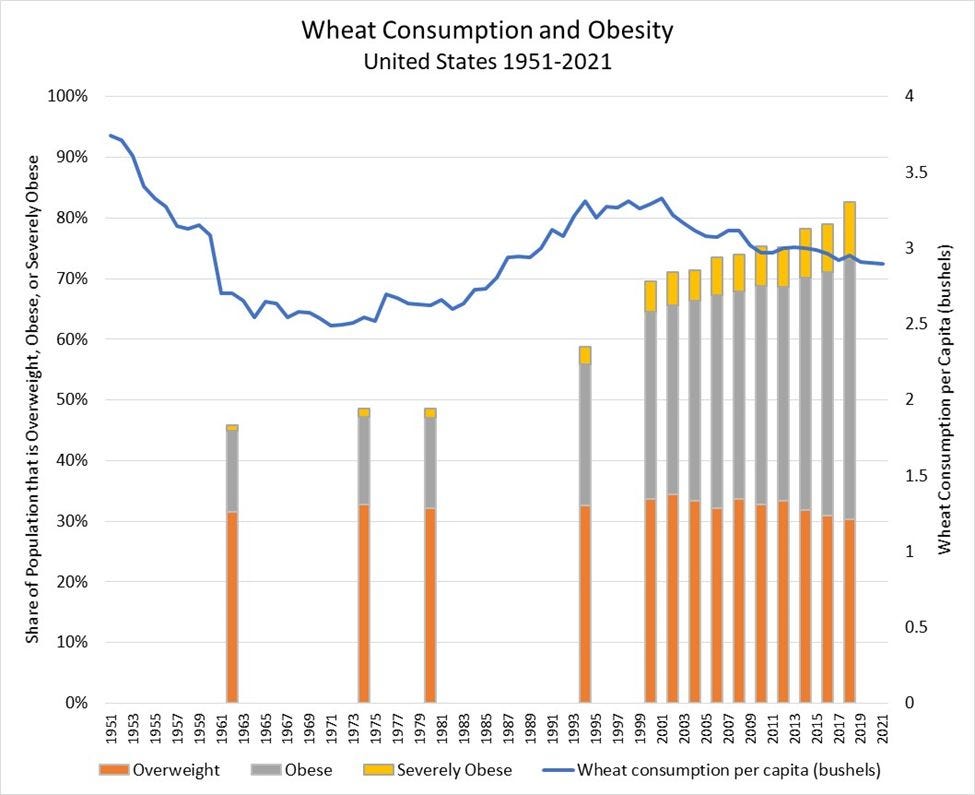

I have only examined these data on obesity recently, but the wheat consumption data are much the same data I had examined some years ago. In the next graph, however, I extend the data on wheat consumption to the interval 1951-2021, and I match those data up with CDC survey data on obesity from 1962-2018.

It is unfortunate that the CDC does not provide surveys of obesity going back to 1951, but, even absent such surveys, it is not obvious that there is much of a correlation between wheat consumption and obesity. After the Atkins diet/low-carb fad starts in the early 2000’s, wheat consumption per capita does go down, … but obesity continues its upward march. Meanwhile, the data suggest that wheat consumption was relatively high in 1951 but steadily fell from about 3.7 bushels per person in 1951 to about 2.6 bushels per person by 1963. Were people getting wealthier through the 1950’s and substituting out of carbohydrates and into other sources of calories? Interesting.

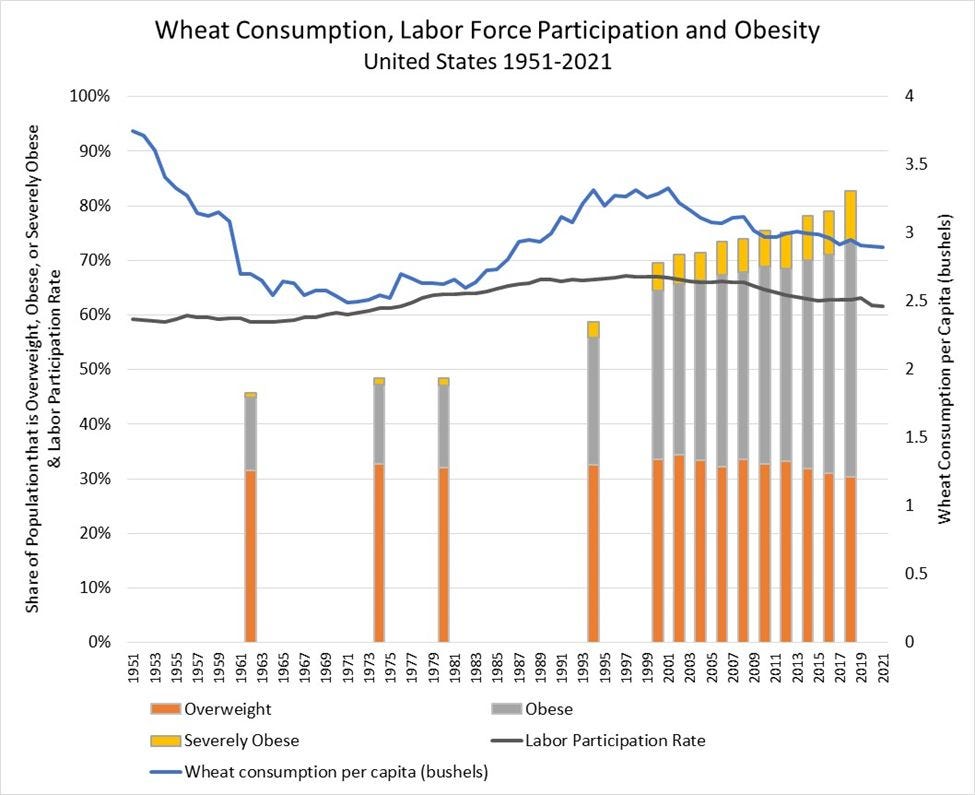

In the next graph I add a measure of labor force participation provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (by way of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis).[4]

Note that the labor force participation rate appears to move tightly with wheat consumption from the late 1960’s forward. An ambitious narrative does suggest itself: People may have substituted out of wheat into other sources of calories through the 1950’s and into the 1960’s, but as people have left the work force post-2000, they have taken more time to cook for themselves—and they’ve secured more calories from sources other than wheat.

Whether or not that narrative is correct, one cannot see an obvious correlation between labor force participation and obesity. To make this point more plainly, I reproduce the graph without wheat consumption:

In this graph I map measures of obesity and labor force participation on opposing axes. That makes it easier to see that the relationship between these things (if any) is complex at the very least. There might be confounding factors.

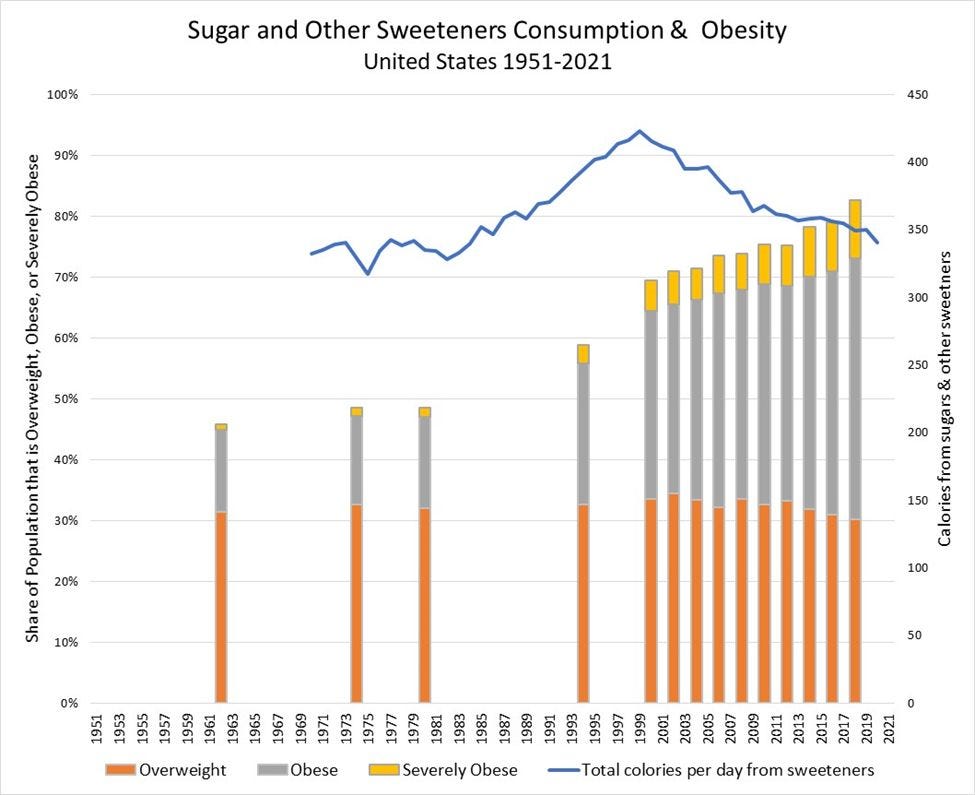

In the next graph I map obesity against per capita, daily consumption of sugars and other sweeteners (mostly corn syrup and honey).[5]

Consumption of sweeteners goes up, and obesity goes up. But then consumption of sweeteners goes down, and obesity continues to go up. What to make of that?

The fact that one cannot graphically identify obvious correlations between any two variables does not preclude the prospect that there are no interesting correlations, and that’s what multi-variable regression analysis is about. Examining pair-wise correlations is all well and good, but there could be confounding factors. If we measure those confounding factors and toss them into a regression equation, we might yet recover an interesting pairwise correlation. Or not.

For fun I did run some regressions. No robust results came of it. Put it that way. These data on sweeteners, on wheat, and on labor participation are not sufficient to identify any interesting relationships with obesity. Carbohydrates may be problematic in some way, but one would have to secure different data to substantiate such a conclusion. As it stands, a popular idea is that carbohydrates do contribute to obesity. Indeed, there is much sentiment out there that avoiding carbohydrates makes it easier to lose weight. Part of the idea is that the body will fuel itself with blood sugar; carbohydrates boost blood sugar; avoiding carbohydrates forces the body to burn fat… but the body runs on blood sugar, and if it does not get carbohydrates, it will synthesize sugars from proteins as well as from fats by a process of glucogenesis. This is something I am really not equipped to talk about. My only point would be that the popular concept of low-carb diets may not be well motivated.

Now. What to make of all of that? My own sense is that, after decades and decades of research, the science of nutrition remains underdeveloped. “The Science” remains deficient. A reason for that would be that underlying processes are complex and getting good data is hard. We thus end up with a lot of ideas which amount more to religion than science. I am not trying to be glib and clever by suggesting that eating your vegetables (along with everything else) and cooking for oneself amounts to robust guidance about how to organize one’s diet.

[1] Gilbert, Robert E. “Eisenhower's 1955 Heart Attack: Medical Treatment, Political Effects, and the "Behind the Scenes" Leadership Style,” Politics and the Life Sciences 27 (2008): 2-21.

[2] See the “Wheat Yearbook Table 05,” https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/wheat-data/.

[3] https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity-adult-17-18/obesity-adult.htm. The surveys in this graph sampled people over intervals spanning the years 1971-1974, 1976-1980, and 1988-1994.

[4] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CIVPART

[5] See the “Sugar and Sweeteners Yearbook Tables,” https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/sugar-and-sweeteners-yearbook-tables/sugar-and-sweeteners-yearbook-tables/.

One of the contributing factors might be the amount of television watched. Not just the time spent sitting around but also all those adverts for snack foods.

I read somewhere that before farming the human diet was enormously varied. I did see an estimated figure for the number of different types of plants, animals and insects consumed. I can't remember what the figure was but it was far higher than that for farming societies. When farming started the range of food types in the human diet contracted greatly. It would be interesting to see how the average height of humans changed over that period.

Thanks for a very interesting article.

Interesting findings. Perhaps the proliferation of certain drugs and chemicals is a factor.