Make America America Again!

American wealth and power emerged despite slavery, not because of it. It was industrialization, free labor, and free markets that made America America.

The main proposition here is: The Country-was-built-on-slavery Narrative is willfully ignorant, self-serving nonsense. And it mostly serves affluent, white elites.

* * *

The Charleston Historic District in Charleston, South Carolina is one of the largest National Historic Landmark Districts in the United States. (Here is a map.) The district originally spanned everything south of Calhoun Street—yes, named for that Calhoun, the proponent of “states’ rights” (slavery) vis-à-vis federal authority—but has since been expanded to occupy much real estate north of Calhoun Street.

Charleston, recall, was where the American Civil War (1861-1865) officially got going. South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union, and the eager secessionists set up cannon across the water from the fort, Fort Sumter, guarding the entrance to the bay. They shelled the fort into submission. Fort Sumter is now a “national monument.”

The historic district designation effectively freezes Charleston in time. At least, that is part of the motivation: to freeze things in time, to save them from re-development, over-development, transmogrification.

I had the privilege of hearing a tour guide explain that Charleston had fallen into a funk with the end of the Civil War. It remained virtually untouched until well after the Second World War. What a gift, then, that antebellum Charleston had been delivered through most of a century virtually intact. The historic district was established in 1960.

What this means is that Charleston avoided much of the development that had attended industrial mobilization during the Second World War. Other port cities like Mobile, Alabama or New Orleans, Louisiana experienced a flood of shipyard work and a flood of people—black, white, all colors—literally coming out of the backwoods country and bayous to take up jobs in the shipyards. War mobilization enabled the entry of hillbillies en masse into the main stream.

Implicit in this story of Charleston having fallen into a funk is that it would not have fallen from an exalted position and would have maintained its exalted position—culturally, economically—had the South not lost the Civil War. There had been a time when Charleston really had been the grandest jewel of the South, and perhaps it still held such status in the run up to the Civil War. But, the suggestion seems to be that enormous wealth had flowed through—and was generated within—antebellum Charleston. Such great flows of wealth would have persisted but for the Civil War.

Could that proposition count as a missing installment in the woulda-coulda-shoulda files that comprise the “Lost Cause” narrative. One part of the Lost Cause narrative (recall) is that the South could have prevailed in the Civil War but for the fact that the North was able to mobilize such great numbers of men and matériel. The politically-correct interpretation of the Lost Cause narrative is that it comprises nothing more than a body of myths that Southern elites used to justify the great losses the South had sustained in their fight to preserve slavery—losses born mostly by non-elites. But, some observers will assign some measure of credit to the bit about the North economically overwhelming the South. The North maintained about three times the population of the South by the time war broke out in 1861, and its industrial base was well more than three times larger than that of the South. The Industrial Revolution was taking hold in the United States, but most of the action was in the North. The largely agricultural South was mostly getting by on exports of cotton to the textile mills of the North, Britain and France.

The question of why wars ever break out is a tricky one, and one can imagine that, were the parties to the Civil War granted a do-over, they’d exercise that option and resolve matters more peaceably. The same could very well go for the combatants on the various fronts of the First and Second World Wars. That said, one could argue that the South’s collective gambit very nearly worked. It wasn’t obvious that the North would be able to maintain the political will to bear the heavy losses that preserving the Union proved to require. But here’s a question: Why did the South force the matter in 1861? Why had the southern states not collectively pressed for secession ten years earlier in 1851 or even earlier as in the year of the Missouri Compromise (1820)? Why wait around for an industrializing North to become ever stronger relative to the South? I have two formative ideas in mind:

On the timing of secession

I have in mind a kind of “Thucydides Trap”: One power presses conflict with a rising power before that rising power can assemble overwhelming capacity and impose its collective will. In the American case, the South was stagnating both economically and culturally. The prospect of success in a collective bid to secede was receding. If the southern states were not going to coordinate their efforts in 1861 and secede, could any one of them ever hope to secede? They managed to coordinate on the idea of taking the gamble; they nearly succeeded; yet, even in success, they would have suffered grievously.

This Thucydides narrative imposes some structure on the timing of secession. The principal driver of the narrative is the increasing gap between the economic development of the North and South, but I think there is qualitative evidence that growth in the southern states had stagnated. (Hold that thought.) So, the matter of an increasing gap involved not merely higher rates of growth in the North and slower rates of growth in the South but also virtually zero growth in the South.

On the motivation for secession

I also have in mind an interpretation of the motivation for secession. I would suggest that the motivation was not so much about maintaining the “peculiar institution” (slavery) in a place that conformed to a static, Hollywood concept of the “Old South” but rather about extending slave labor to new territories and states in the West. Indeed, the question of slavery directly impinged the question of how the new United States would add states to the Union.

Even before the American Revolution (1775-1783), the British colonists were inspired by the idea of extending their jurisdictions all the way to the Mississippi River, and some of them were intent on extending their jurisdictions into the Ohio River Valley (north of the Ohio River). Thus, it was not for nothing that the colony of Virginia had dispatched a sequence of contingents of Virginia militiamen to deliver messages to a French contingent that had set up a fort at the point where the Allegheny and Monangahela Rivers join to form the Ohio River (in the heart of present-day Pittsburgh). The second of such ventures involved a fraught and poorly managed encounter with a French contingent that was intent on going the other direction to deliver its own message to the British and their Virginia cohorts. The leader of the Virginia contingent, a 21-year-old George Washington, found himself having to report back to the British authorities that things had gotten a little out of hand; the French official he was supposed to talk to ended up getting killed in an encounter with George Washington’s contingent of militiamen and native guides. The shots fired in that engagement may very well have constituted the first shots fired in the world war (chiefly pitting globalizing British empire against globalizing French empire) that was the Seven Years’ War (1754-1761).

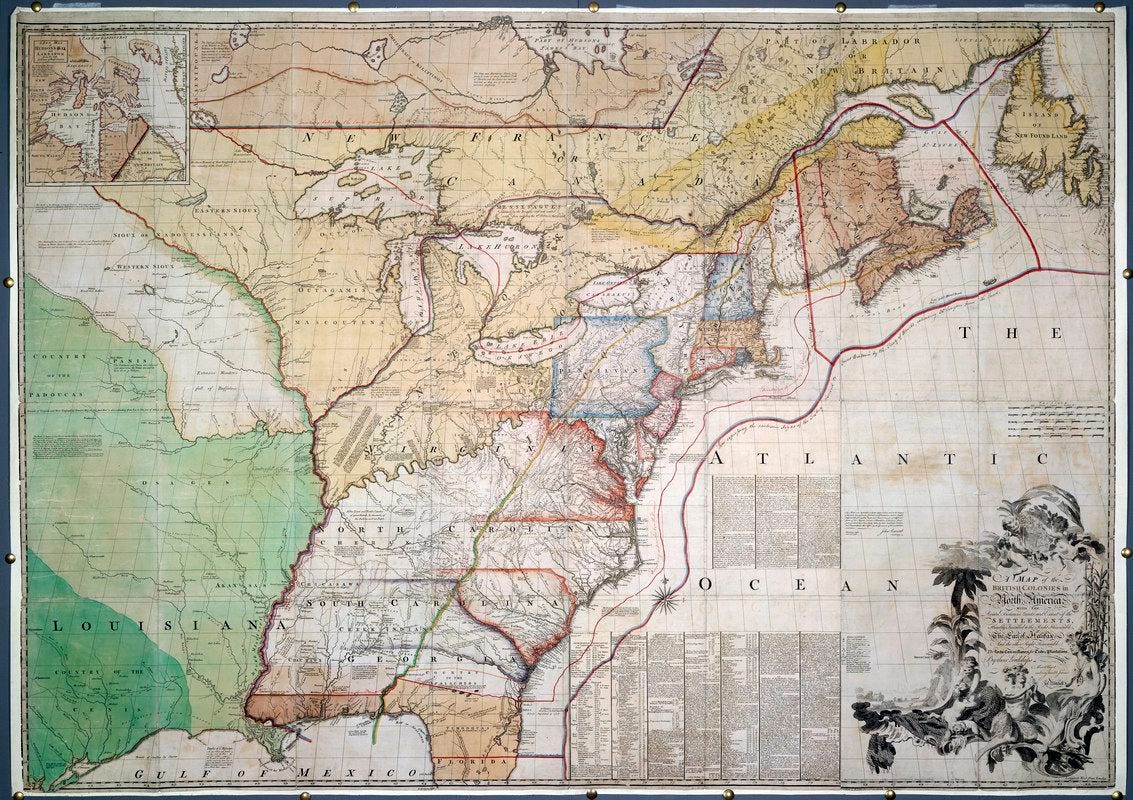

Here is a map from 1775 that illuminates the (potentially overlapping) claims of various British colonies to territories extending all the way to the Mississippi River. Note that these claims do not extend north of the Ohio River into the Ohio River Valley. In the settlement to the Seven Years’ War, the French ceded the Ohio River Valley to the British, but, with their Proclamation of 1763, the British authorities barred the colonists from settling that region. That fact had surely inflamed pro-independence sentiments, for one motivation for fighting the French had been to clear the way for settlement in that region.

https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:hx11z549x

Flash forward 12 years to 1787, and the then-independent United States establishes two initiatives that directly relate to slavery. First, the Congress passed “An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States North-West of the River Ohio," the “Northwest Ordinance” for short. The Northwest Ordinance established a process for admitting new states, carved out of the region north of the Ohio, to the Union. The sixth of the six Articles that comprise the Northwest Ordinance bars the extension of slavery to anywhere in the territory.

One has to wonder what representatives in Congress from the southern states had to think about this, which brings us to the second item on the agenda in 1787, the Constitutional Convention that same summer. One matter the Constitution had to address was the apportionment of seats, by state, in the lower chamber of Congress, the House of Representatives. Conspicuous for being so grotesque must have been the compromise according to which the slave population of the southern states would be counted towards representation in the House. Specifically, representatives in the House would be weighted by population. Infamously, 60% of the slave population in a given state would be counted toward that state’s weight. Progressives point to this provision as Exhibit A in the argument that “the United States was founded on racism and slavery… The Constitution only counted a black person as three-fifths of a person!”

It is not, I would suggest, obvious what such a declaration means. It has a certain intuitive appeal, but it’s a statement that comes from either willful ignorance or a willful effort to deny the much more interesting and elaborate story of what was going on. Specifically, Convention delegates had to grapple with the problem of how to dispatch the matter of slavery, and one can imagine that the Convention could have yielded two United States, a free United States of the North and a slave-holding United States of South. But, instead, the delegates came up with the 60% rule as a way of getting all of the states to go forward with a single, united United States of America.

Ostensibly united the states did thus proceed, but the question of whether or not to extend slavery to new states and territories remained an outstanding issue. Indeed, the issue was never definitely resolved until four score and seven (plus one) years after the Constitutional Convention with the resolution of the Civil War in 1865. Four percent of the male population—one in twenty-five men—perished in the fight to resolve the matter.

A great puzzle about the Civil War would appear to be the question of why so many Southern people of modest means would fight to protect the interests of the much fewer elites in the South. A formative answer is that these people were fighting less for the interests of established elites in the established South and more for the interests of people like themselves who endeavored to reinvent themselves in the unestablished West. Such people had already been streaming in to the West. They included, for example, the original Texans who, in the 1830’s and 1840’s, had accepted the invitation of the Mexican government to venture into what was then Mexican territory and roll back the Comanche threat. They then ended up fighting off the Mexican army and then established their own independent Republic of Texas. These people had already demonstrated that they meant business. (On the Texas experience, I highly recommend the encyclopedic and beautifully-crafted Comanches, T.R. Fehrenbach, 1986.)

This idea—whether roughly correct or largely not—that Southerners of modest means were motivated to fight for the right to export slavery to new territories in the West really first came to me when reading an original copy of Human geography of the South – a study in regional resources and human adequacy (Rupert Bayless Vance, 1932). I became interested in this book after finding so many nice citations to it in An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion (1939).

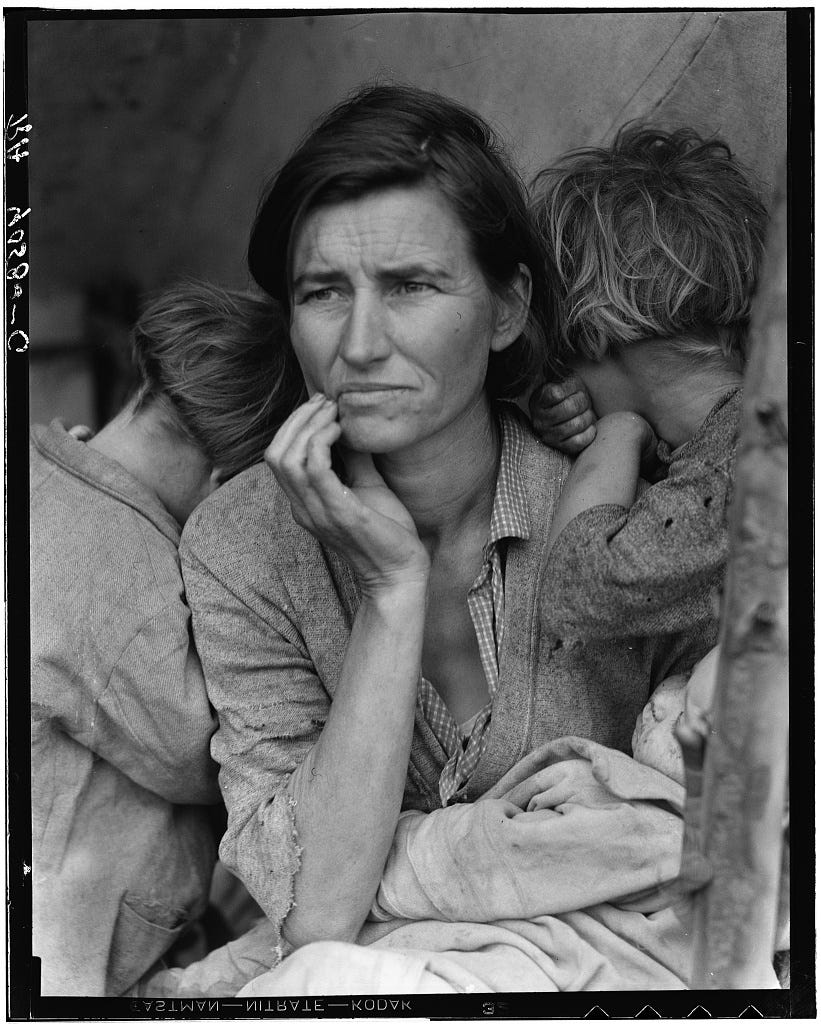

Exodus is a collection of Dorothea Lange photographs from the 1930’s complemented with essays by economist and “committed New Dealer” Paul Taylor. That most iconic photo of Lange’s, “Migrant Mother,” does not show up in this particular book, but it is a very, very illuminating book. Human Geography, meanwhile, does not make for a breezy read, but one has to be impressed with people who demonstrate so much commitment in composing such a broad and thorough body of work.

“Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California” 1936 https://www.loc.gov/item/2017762891/

Credits for all black-and-white photographs here: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives. https://www.loc.gov/rr/print/res/071_fsab.html

The early part of Human Geography reveals an “Old South” that was more of a dynamic, frontier society, ever reaching out farther, than a static society of gentlemen planters. The gentlemen planters had long been established. The un-established and un-landed could take on the hazards of the frontier—hazards like fighting Amerindians, and then Mexicans, and then more Amerindians—for the opportunity to exhaust the agricultural productivity of the land before abandoning the land and moving out again to the next frontier. Behind those impatient frontiersman would come the rather more patient immigrants—many from German principalities or regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—who would settle down and invest efforts in restoring the productivity of exhausted lands. Further West, frontiersmen and then the Central Europeans traded in agriculture for ranching on the wastelands of the high plains. They had learned from the Mexicans that ranching provided a way of using otherwise useless lands.

It may be no accident that films about the West disproportionately feature Civil War veterans extracted from the Confederacy. Examples would include The Outlaw Josey Wales (Clint Eastwood 1976), the Yellowstone prequel 1883 (2021), and Hell on Wheels (2011-2016 with Colm Meaney as real-life railroad magnate Thomas Durant).

Missing from this narrative, thus far, is the question of why these Southern frontiersmen of modest means were interested in exporting slavery to new territories in the West. The question of why people would exploit slaves rather than just pay laborers in a free labor market is itself a puzzle. It is not as though slaves labor was free. Slaves had to be maintained at some cost if one expected them to be productive. At the same time, slaves might have less incentive to work as hard as free laborers. Free laborers could at least enjoy the prospect of building up their own capital and therefore had some incentive to invest in their own futures. When one does all the accounting, could one find that free labor really was sometimes less cost effective than slave labor?

That said, one might guess that gang labor (slave labor) on cotton plantations might be easier to rationalize as a matter of cold accounting than say deploying slave labor on the high plains of West Texas. But, there was a lot of interest in extending slave holding to the West—see, for example, “Bleeding Kansas”. People demonstrated great interest in fighting for it. But would slave labor have proven to be less rationalizable further out on the frontier? I leave that as an outstanding question.

Incomplete though my sketch of the motivation for secession may be, it does suggest some answers to some puzzles. It suggests that the prospect of extending slavery further West was a very big part of the motivation for secession. Indeed, the issue may have been less about the secession of particular states in the antebellum South and more about the construction of a polity that would support the extension of slavery to the frontiers. There was a non-trivial body of Southerners who were fighting not so much for the rights of gentlemen planters in South Carolina to maintain their glorious estates in South Carolina but rather for the right to compete with the North to colonize the West.

Note what that means. Had the South prevailed in the Civil War, the fight to extend slavery to the West would not have ended. The slave-holding South would yet have had to compete with the North to settle territories in the West. Which brings us back to the 60% rule established in 1787: The compromise of 1787 kept the fight over what to do about slavery in the existing states and in new territories in-house. In contrast, failure to compromise in 1787 would have situated the fight between competing houses. That said, in-house compromises failed to definitely resolve the matter over the course of 84 years (from 1787 to 1861). The demand to secede in 1861 effectively amounted to a bid to fight into the indefinite future over the extension of slavery into the West. Southern victory in the Civil War would merely have set the stage for more fighting. The actual Northern victory in 1865—if we can call it victory—did have the advantage of definitely resolving the slavery issue. The fighting was over. That said, the narrative sketched here leads me to this question:

How much for “40 acres and a mule” in 1865?

“Forty Acres and a Mule” is the name of Spike Lee’s film production company. The phrase was inspired by the “Special Field Orders No. 15” that General William Tecumseh Sherman issued on January 16, 1865. His Union army set out from Chattanooga, Tennessee following the train line all the way to the great, Confederate logistical hub that was Atlanta, Georgia. The Confederates, of course, fought Sherman’s army all the way, tearing up the tracks as they retreated. But, long story short, Sherman’s army eventually took Atlanta, and then it cut lose from supply via the rail line and made its epic “March to Sea”: The army marched without the prospect of re-supply by train and without access to telegraphic communication from Atlanta to the port of Savannah. By the time the Union army had secured Savannah, it had taken on a great train of just-freed slaves who had fled the plantations as the army rolled through. What to do with these people? Special Field Orders No. 15 would confiscate about 400,000 acres of land ranging from the northern coast of Florida (north of Jacksonville), along the Georgia coastline (and thus encompassing the environs of Savannah), and into South Carolina (right up to Charleston). Freed slaves in the great train of slaves following the Union army would be set up in the 400,000-acre reserve with plots of about 40 acres each. The implementation of The Special Orders did not get very far by the time Abraham Lincoln was assassinated only a few months later. Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, undid the policy.

One can imagine the kinds of propositions that the phrase “Forty Acres and a Mule” had come to stand in for: Broken promises? Non-credible commitments? A future of prosperity and self-sufficiency swapped out with a future of penury and dependence? These are surely the kinds of things that Spike Lee had had in mind, and one can wonder: How much value in 1865 did that 400,000 acres comprise?

One can imagine that, in 1865, the estates that made up much of that 400,000 acres would have had more value (by virtue of being more productive) were they not to be broken up into independently-managed, 40-acre lots. Indeed, one can imagine that the slaves receiving allotments of 40 acres could collectively do better by selling the land back to the estate owners and then using their proceeds to set up shop elsewhere. Or, maybe the value of the big estates really didn’t exceed the collective value of 40-acre lots out of which the new owners could expect to generate little surplus beyond their own subsistence requirements. Was there really much value in agricultural properties that would not have been exhausted over the course of the previous 200 years? Basically, was “40 acres and a mule” really worth much?

These days some of those 400,000 acres will surely account for much value. Many (most?) of those acres will have been redirected to purposes other than agricultural production. So, there’s a finance question: If a given 40-acre lot had been largely unproductive from 1865 to, say, 1940 and had only been capable of supporting high-value purposes after 1940, then how much would someone have been willing to pay for that land in 1865? Stated differently: If you own an asset that will only start yielding returns more than half-a-century into the future, then how much would someone be willing to pay to buy it from you now? Possibly very little. So, there’s my proposition: It is not obvious that “40 acres and a mule” was really worth anything in 1865. Those 40 acres and that mythical mule may have provided a basis for subsistence, but not for accumulation of wealth.

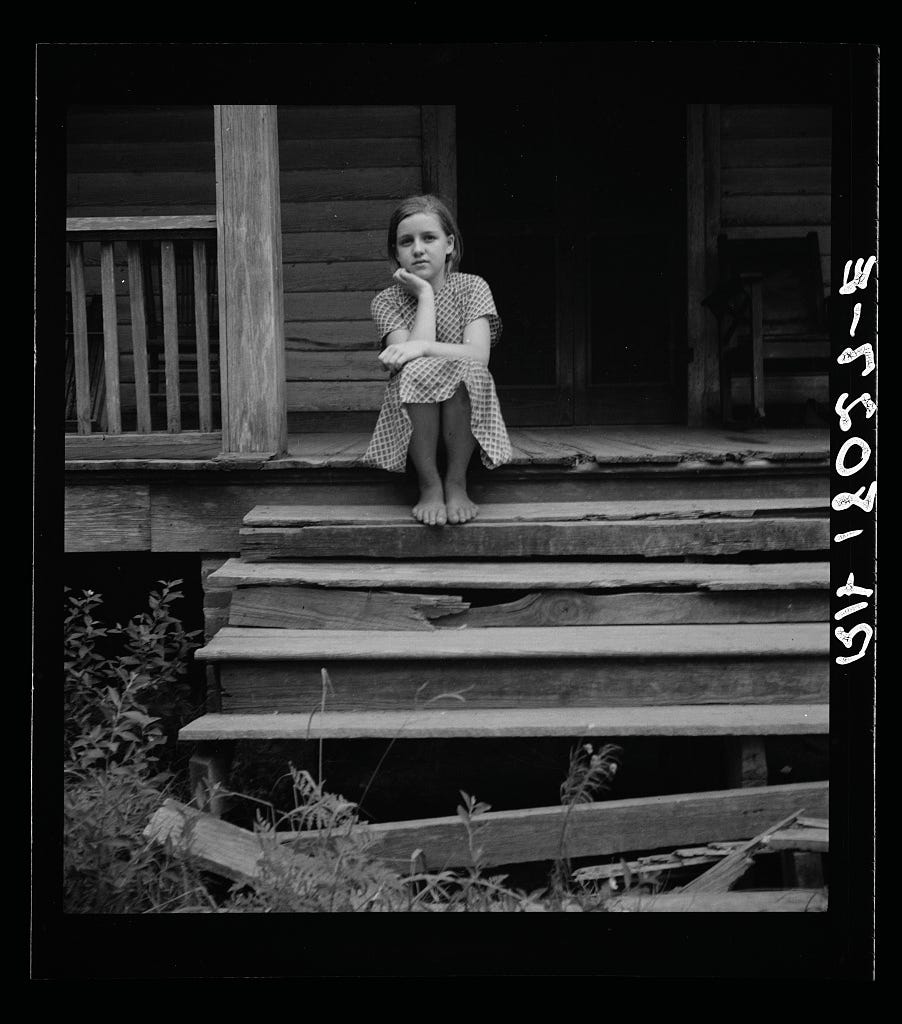

I picked the year 1940 for a reason. One can’t help come away from readings of An American Exodus and Human Geography of the South with the impression that agricultural productivity in the oldest regions of the South as of the 1930’s may not really have exceeded agricultural productivity in 1865. The grand plantations had withered. The plantation houses were dilapidated. People, both black and white, really did live like the people (sharecroppers in the Depression-age South) who populated such films as Sounder (1972).

Dorothea Lange’s photos attest to the conditions in parts of the “Old South” as of the 1930’s. Consider this photo “Antebellum plantation house in Greene County, Georgia” 1937 (in the public domain, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017770449/):

“Antebellum plantation house in Greene County, Georgia” 1937

There she is, the scion of an antebellum-era gentleman planter from Georgia, standing in the decaying remains of a plantation house. Note to the reparations crowd: You can ask her for reparations, but she ain’t got none. And, she is no longer of this world, anyway. The reparations treasure chest was already empty in 1937, and it was likely close to depletion in 1861 at the beginning of the Civil War. Too late!

Meanwhile, here are a few images of people of modest means living in such decaying plantation houses:

“Ex-slave and wife who live in a decaying plantation house. Greene County, Georgia” 1937 https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/fsa/item/2017770451/

“What was once the ‘Big House’ is now occupied by a family of white tenants who live in part of the crumbling mansion and farm a small piece of the nearby eroding fields. Greene County, Georgia.” 1937 https://www.loc.gov/item/2017770481/

But, admittedly, some people did manage to make a good go of it:

“Home of Negro landowner, Greene County, Georgia. This man has owned his land since 1913. He has raised ten children here.” 1937 https://www.loc.gov/item/2017770443/

Beautiful place!

One can wonder how representative a few photographic vignettes plucked from An American Exodus are, and one can speculate more generally about how representative the entire portfolio of work in An American Exodus is. But the vignettes suggest compelling interpretations of what was going on. Human Geography of the South imposes yet more structure.

* * *

The American experience during the Second World War picks up where John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath (1939) and An American Exodus (1939) leave off. The agricultural sector across the United States was going through broad mechanization through the course of the 1930’s. A lot of people, black and white, were being “tractored off” the land, and, much like Steinbeck’s protagonists, the Joads, many ended up picking peaches in orchards in California. It was the young men among them who themselves ended up getting plucked up and sent off to war in the Pacific, in North Africa, Italy, France and finally, Germany. Those young men each drew a challenging card from the deck.

These people were, by modern standards, living in penury before mechanization. Mechanization merely took away what little means they had to subsist. But, the main thing is, there were a lot of poor people both before and after mechanization. They were black. They were white. They came disproportionately from the South and from the southern plains. They were disproportionately the inheritors of the legacy of the Confederacy, and that legacy was economic stagnation with or without civil war. And, yet, the Progressive orthodoxy of our time is this cartoonish idea (never explained) that somehow the great power and wealth of the United States derived from slavery. Indeed, the Constitution, Progressives claim, was designed to consolidate the “peculiar institution” of slavery by providing for the protection of property rights. Private property bad. Implicitly, the collectivization of everything good, notwithstanding the fact that experiments like collectivization in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge (1975-1979), collectivization under the Soviets’ First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932), and collectivization under Mao’s “Great Leap Forward” (modeled after the Soviets’ Five-Year Plan) resulted in famine and, respectively, the deaths of millions, millions, and tens of millions.

A casual review of the experiment in the United States in the run up to the Civil War and following the Civil War suggests a much more compelling narrative: “The South” was less than prosperous before the Civil War, and it remained stagnant after the Civil War. Cities like Charleston were already stagnant. In contrast, industrialization in the North enabled the development and concentration of wealth (also in the North), and it is no accident that Southerners, both black and white, started to move in large numbers to jobs in the industrializing cities of the North. From the stage play Cuttin’ Up (2005) one gets lines like “Black folks migrate in straight lines.” Thus exclaims one barber to the other barbers in the shop. Folks from Mississippi would get on the Illinois-Central railroad and head straight up to Chicago. Folks from South Carolina ended up, disproportionately in New York and Boston. “So, if you’re from South Carolina, and you end up in Chicago, people wonder what’s wrong with you.”

That’s why Chicago Blues have Mississippi roots. Recall, for example, that scene of Mississippi native John Lee Hooker in The Blues Brothers (1980). Meanwhile, Indianola, Mississippi native B.B. King didn’t make it as far Chicago, noting in an interview on Jazz FM radio (London) in 1993 that he had only gotten as far as north as Memphis, Tennessee – which, to him, seemed “as far away as London.”

Those migrations comprise part of the mythologized “Great Migration,” but, if one were to examine census data (and I have) one can see waves of Great Migrations of black and white peoples. Johnny Cash’s “One Piece at a Time” does come to mind. It opens thusly:

Well, I left Kentucky back in '49

And went to Dee-troit working on assembly line

The first year they had me putting wheels on Cadillacs

Every day I'd watch them beauties roll by

And sometimes I'd hang my head and cry

Because I always wanted me one that was long and black

People of modest means were on the move out of a stagnant and stagnating South to other parts of the country—to other parts, where great wealth and power were actually being generated. The Country-was-built-on-slavery narrative is just self-serving nonsense.

* * *

This wide-ranging essay constitutes an early exploration of stuff I’ve been thinking about for some time. And assembling this material has helped me to better appreciate how much more work I yet need to do in thinking of about the use and abuse of Constitutional history. A handful of essays may yet come of the work, and I’ve gotten to thinking that such essays may comprise good installments in a book titled something like American Myths. Some of those myths correspond to Progressive orthodoxy, but many of those myths fit into more traditional, Old School orthodoxies as well. Watch this space.

Economy by 1861 favored paid labor over slave labor, many slave owners understood that but their investment was at risk. Not sure about western slave expansion in that slave populations couldn't support much expansion. OTOH, the South felt the Congress was passing laws they felt were harmful.

The 5/8ths compromise was way to recognize slave owner property rights while reducing states representation. Founders clearly wanted slavery to go away and included a curious phrase to end all importation.

Many who fought were convinced of an invasion from the north that had to be countered. But it did split families. Many I suppose felt like a war survivor relative with a gravestone "My country failed me"

There seems no practical reason why a Southern frontiersman or settler would want to extend slavery to the West, but perhaps the idea of slavery was like a cultural talisman for such people, an extension of their national identities. Again, of no personal, practical value to them; but if you attacked it, you were attacking their nation and themselves. So naturally they wanted to see it expand westward.

That's one theory, anyway.