Same as It Ever Was: Nothing New to See in COVID Data

COVID data tell us nothing we could have already known for more than a year.

I post this essay for two reasons. First, I will be citing it in at least one following essay, and, second, this essay documents the fact that much of what we know now about the progression of COVID through the population was known – or was abundantly knowable – well more than a year ago. Most notably, it was obvious early on that the COVID phenomenon was more than just a disease phenomenon. It was obvious that COVID itself was taking away immunocompromised people – people already susceptible to near-term death – but there yet remained an appreciable stream of excess non-COVID fatalities among younger, healthy, working-age people. Indeed, excess mortality not attributed to COVID among younger people has remained stubbornly high. Why is this?

It seems that some voices in the media have, in early 2022, started to pick up on this phenomenon of persistent excess mortality among younger people. It is not really possible to pin down, using publicly-available data, exactly why younger people have been dying, week to week, at rates about 40% to 50% higher than pre-COVID levels, but it is hard not to suspect that poor public policy has something to do with it. Surely destroying small businesses by the tens of thousands – and diverting $trillions to billionaires – has something to do with it. Surely allowing fentanyl to pour unchecked over the borders has contributed. But, it is not politically-correct to fetishize the fatalities of younger, working-age people. It is only politically-correct to fetishize COVID fatalities.

Some observers will note that counts of COVID fatalities must surely be inflated, given the perverse-incentives induced by the fact that healthcare providers secure bounties of about $48,000 for every case they count as a COVID fatality. One way to get away from distorted counts is to examine excess mortality. The COVID phenomenon has induced mortality in excess of pre-COVID averages. In other words, it is not strictly the case that COVID phenomenon merely induced fatalities that would have occurred in the absence of COVID. Otherwise, there would have been no “excess” in “excess mortality”. But, the case remains that, notwithstanding the likelihood that fatalities attributed to COVID are inflated, those counts of COVID fatalities still don’t account for a lot of the excess mortality. Something very bad has been going on through the entire course of the COVID experience. The fact that media may only now be figuring this out is just another discredit to the media, but better late than never.

I first posted this essay (below) on LinkedIn on January 10, 2020. The qualitative conclusions from back then do not change. They hold up well. Think about that. We have known what there is to know. COVID is boring.

January 10, 2021

COVID Mortality in the United States:

Did It or Did It Not Induce Excess Mortality in 2020?

I examine weekly counts of fatalities publicly posted by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) for the weeks ending January 10, 2015 through November 7, 2020. These data include indications of the most frequent “underlying” causes of death.

I develop a baseline of expected mortality in 2020, and I use that baseline to derive an estimate of weekly “excess mortality” through November 7, 2020.

The year 2020 was emerging from a mild 2019/20 cold-and-flu season and was not generating mortality in excess of baseline mortality – until fatalities attributed to COVID-19 started to surge in April 2020.

Evidence of excess mortality would be consistent with the proposition that the coronavirus phenomenon had generated fatalities in excess of those that would have obtained absent COVID-19, but excess mortality alone would not prove that COVID had generated those “excess” fatalities. Indeed, that remains a tricky question: How much of the COVID toll can we attribute to mortality that would not have otherwise occurred? And then there is the flip-side of that coin: How much of the COVID toll can we attribute to people who would have died, anyway, in 2020? I endeavor to impose on these questions as much structure as the data will permit.

The answers to these questions matter, because there is some intuition out there that, examining the COVID numbers in isolation makes the COVID phenomenon appear more extreme than it is, and that once one compares COVID fatalities to total mortality, one may see that COVID actually had little effect on total mortality; the coronavirus phenomenon may end up being an exercise in relabeling fatalities that would have occurred anyway. The results presented here suggest that COVID has contributed to higher mortality than would otherwise have occurred absent COVID, but the phenomenon is complex in that it is both more severe (in some respects) and less severe (in other respects) than a simple count of COVID fatalities alone would suggest.

Excess mortality through November 7 amounts to very nearly 265,000. Meanwhile, the CDC attributes nearly 218,000 fatalities to COVID. Even if we were to attribute all of those COVID fatalities to “excess mortality”, we would still have to account for at least another 47,000 in excess mortality. I say, “at least,” because every COVID fatality that we do not attribute to excess mortality amounts to another excess fatality to account for. Why did such non-COVID excess mortality occur? Did the institutional response to COVID have something to do with it?

The coronavirus phenomenon is complex in that there are reasons for attributing some volume of COVID fatalities to non-excess mortality – that is, to fatalities that would have occurred with or without COVID. But, at the same time, there are reasons to suggest that some fatalities not attributed to COVID could have been attributed to COVID. The COVID accounting problem is even more complex in that it appears to have induced a non-trivial volume of non-COVID fatalities. Among other things, “too many” fatalities attributed to Alzheimer’s disease, dementia and various manifestations of obesity (such as diabetes and hypertension) show up conspicuously in the data just as COVID fatalities started to surge. At the same time, “too few” fatalities attributed to cancers and chronic lower respiratory disease show up.

The missing cases of cancer and chronic lower respiratory disease (about 15,000) were likely swept up in the COVID fatalities. These missing cases are good candidates for fatalities that would have occurred in 2020 absent COVID.

The “too many” cases of obesity-related conditions (about 22,000 cases of diabetes, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease) are good candidates for cases that may have been aggravated by COVID infections. Many of these cases may, nonetheless, have been sufficiently severe such that they would still have yielded fatalities in 2020 even absent COVID.

By March researchers had identified a likely molecular mechanism that would make obese individuals particularly vulnerable to COVID infection. Obese individuals maintain larger volumes of adipose tissue, and adipose tissue supports large numbers of ACE2 receptors. Coronavirus is able to latch on to ACE2 receptors and invade cells more efficiently.

The “too many” cases of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia (about 14,000) are good candidates for non-COVID fatalities that could have been avoided but were nonetheless induced by the institutional response to COVID.

The far “too many” cases of excess mortality not attributed to either the most common underlying causes or to COVID (about 32,000) are also good candidates for fatalities that could have been avoided by better institutional responses to COVID. These 32,000 fatalities might reflect part of the toll imposed by lockdowns.

Non-COVID mortality tracks the peaks and troughs of COVID fatalities. This is consistent with COVID inducing both direct and indirect epidemiological effects on total mortality as well as inducing indirect effects derived from institutional responses to COVID.

Excess mortality accounts for nearly 10% of all mortality through November 7.

Comparisons of COVID-19 to the Spanish Flu of 2018 are irresponsible in that (1) the median age of death attributed to Spanish Flu was 28 whereas the median age of death attributed to COVID is about 80; (2) the death toll from Spanish Flu was a much larger and took away people who, on average, had many decades of life yet to live.

Results reported here depend on the assumption that the susceptibility of the population to disease and mortality from one year to the next is roughly comparable, but one can imagine that a population emerging from a mild cold-and-flu season, such as the population that entered the COVID pandemic, would be less healthy and more susceptible to COVID. Had the 2019/2020 cold-and-flu season been harsh, the effects of COVID may have been discernibly diminished.

Total mortality in 2021 may diminish and may trace a trajectory discernibly lower than the estimated benchmark mortality, because COVID will have already taken away the most vulnerable people.

In November 2020 John Hopkins University posted a notice about a study that purported to demonstrate that fatalities attributed to COVID-19 have not appreciably contributed to total mortality in the United States. Indeed, the researcher, economist Genevieve Briand, went on to suggest that, during the peak of COVID fatalities in April, an appreciable volume of non-COVID fatalities had actually been attributed to COVID. Among other things, an appreciable volume of fatalities from heart attacks and other circulatory conditions appear to have gone underreported at just the time that COVID fatalities were ramping up. Taken all together, the COVID phenomenon amounted to a relabeling of fatalities that would have occurred in 2020 absent the advent of COVID. Thus, while COVID fatalities might have appeared to spike, total fatalities might not have changed much. One is invited to conclude (it seems) that while the spike in COVID fatalities would appear to be a source of much merited distress, the reality is that a proper accounting of total fatalities shows no appreciable increases. The distress is not merited.

I have not had a chance to see an actual paper, but I had stumbled upon Dr. Briand’s video presentation of November 11. The presentation, titled “COVID-19 Deaths: A Look at U.S. Data”, is posted here:

I have taken some time to review much the same data that Dr. Briand had secured. Dr. Briand and I both work out of data publicly posted by the CDC. The CDC sits on top of much richer data and would be much better situated to study the effects of COVID-19 on total mortality, but those of us outside of the CDC must venture forth with the data we have, not with the data we wish we had.

In this short note I advance some conclusions, observations and hypotheses that may yet inform further research. I offer conclusions that I think the data can support. I offer observations about patterns in the data that can inform how we think about the processes that generate mortality statistics. I then pose some ideas about how one might expect mortality statistics to evolve over the coming year.

My first conclusion is that it is hard not to discern an effect of COVID-19 on total mortality in 2020. The year 2020 appears to have been emerging from a mild 2019/2020 cold-and-flu season and was on pace to generate nothing more than a baseline count of total fatalities – one cannot discern evidence of “excess” mortality in early 2020 – but in April 2020 that changed. At the same time, however, the mortality data are consistent with what everyone already knows: COVID’s toll has been concentrated on people who were already bearing a heavy disease burden. No surprise these people tended to be elderly or otherwise immunosuppressed. Yet, the conclusion that COVID did induce an increase in total mortality would imply that these most vulnerable people would have lived a little longer – but not obviously much longer. How much longer remains a question: one month, one year, two more years in a nursing home?

The data examined here will not support a finely-tuned answer to the question of “How much longer?”, but just asking it is important, because it imposes some discipline on our characterization of the burden of the disease on society. Many observers have breathlessly compared the coronavirus phenomenon to the Spanish Flu of 1918. The comparison is deeply unserious. The CDC estimates that the Spanish Flu took away about 675,000 Americans. Proportionally, that would come to about 2.3 million Americans in 2020. The greatest part of the tragedy, however, was the fact that the median age of death attributed to the Spanish Flu was about 28. The Spanish Flu took away people just coming in to their physical prime. Indeed, one might be shocked to know that more American soldiers fighting in France in 1918 succumbed to Spanish Flu than had been taken by German bullets and shells. No less shocking is the fact that these young people were the opposite of immunosuppressed. Their strong immune systems induced “cytokine storms”, immune responses so strong that the victims ended up drowning in fluids accumulating in their lungs.

Meanwhile, the median age of death attributed to coronavirus is either 79, 80, 81, 82 depending on what country one looks at. (In Italy it’s 82.[1]) In all cases the median age of death attributed to COVID-19 is very nearly the median age of death from plain old death. In other words, COVID really is taking away the most vulnerable. Harsh, but not as harsh as Spanish Flu in that the Flu deprived people of decades of life and imposed disability on many of the young survivors. Indeed, the age distribution of COVID fatalities is more forgiving than even that of a harsh flu season in the United States in that the flu will take away a higher proportion of young children – and we do not close schools to accommodate the flu. American soldiers in France and a modest number of young people at home during, say, the 2017/18 cold-and-flu season may have been deprived of 50, 60, 70 years of life. Comparing COVID to Spanish Flu is not helpful.

To recount: COVID has taken a toll of people who yet had some modest amount of time left to live. If all of these people really were on the absolute verge of death – if they were likely to have imminently died anyway – then COVID would have had little or no discernible effect on total mortality. But it has had some discernible effect. The data are consistent, however, with that effect being far less harsh than a simple count of fatalities might suggest. The people who have succumbed to COVID-19 may, on average, have had some time yet to live, but it is not obvious that they would have had much time. Getting a finely-tuned estimate of the time they would have had would at least require a thoughtful accounting of underlying morbidity and age. It is something the CDC would be better equipped to pursue given its superior access to data.

My first observation is that mortality data exhibit obvious seasonality across the most prominent causes of death. That alone might strike one as a little surprising. Why, for example, should cancers exhibit seasonality? More striking, however, is the fact that seemingly distinct causes of death exhibit much the same seasonality. Respiratory conditions like flu or pneumonia may exhibit certain expected seasonality with deaths rising in the colder seasons and retreating in the warmer months. But deaths attributed to circulatory events (heart attacks, strokes and such) exhibit the same seasonality. Even cancers exhibit the same seasonality albeit less dramatically.

One thing one can get from this is that a salient aspect of old age is immunosuppression. Even cancers reflect immunosuppression. Before effective treatment protocols for HIV became available, the people who acquired AIDS – Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome – did not die from AIDS. Not directly. They succumbed to opportunistic infections and unusual cancers. And this raises a question about how we should account for fatalities induced by AIDS. Did a person die of AIDS or from Kaposi sarcoma (a cancer)? Alternatively, did that person succumb to an unusual pneumonia? More technically: Did health practitioners indicate such cancers or pneumonia as the “underlying” causes of death, or did they indicate AIDS? It is no accident that the medical field innovated concepts like “AIDS related cancers”. Assigning causes of death is an imperfect business.

The CDC data assign “underlying” causes of death to fatalities corresponding to the most common causes of death. Underlying causes are not always specified. I indicate those unspecified cases as “All Other”. The average age of people succumbing to “All Other” causes would surely be lower than those of people who had succumbed to the most common causes, but the data do not afford a test of such an hypothesis.

The data are consistent with the idea that that people, immunosuppressed or not, are under more duress in the colder months. Immunosuppressed individuals, already under the duress of dealing with heart conditions or other conditions, find themselves under even more duress. They get a bad cold, and the added stress of the infection kills them. The cold may induce a heart attack. But, if we are to assign a single mode of death, what should it be? A generic diagnosis of “old age” would have something to recommend it insofar as one could credit death to immunosuppression. Immunosuppression would also account for the tight correlation of the frequency of seemingly disparate modes of death.

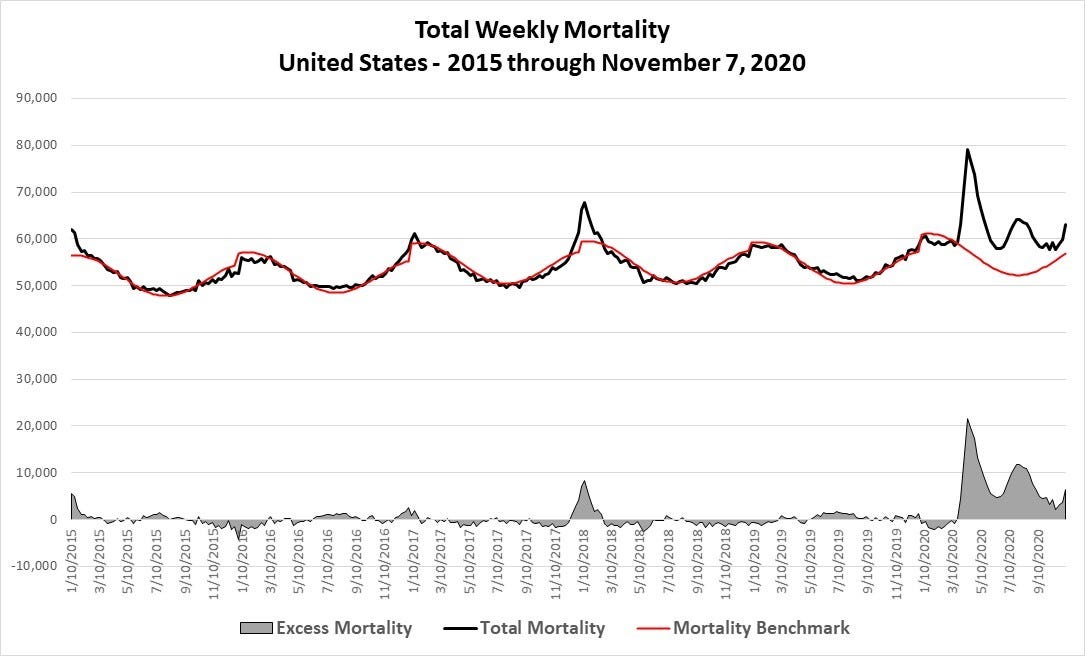

On to the data: I build up results through a series of graphs. The first represents total weekly mortality in the United States for weeks ending January 10, 2015 through November 7, 2020. I ignore data available after November 7, because they appear incomplete as of the writing of this note.

What would a Martian just landing on Earth today make of this graph? Visual inspection alone reveals obvious seasonality in the data. Fatalities peak during “cold-and-flu season” and moderate through the warmer months. The living is easier in summertime with fatalities in each year coasting to a nadir in August. Mortality tends to peak in January. That peak can be conspicuous, as in January 2015, January 2017 or January 2018. In contrast, the cold-and-flu seasons of 2015/16, 2018/19 and even 2019/20 do not exhibit conspicuous peaks. Meanwhile, the year 2020 does stand out in that the 2019/20 cold-and-flu appears to have been modest, but mortality then spiked in April 2020. This spike is the first discernible evidence of COVID-19.

Mortality exhibits two conspicuous peaks in 2020, in April and then again in August. It increases again coming in to November. In August one might have expected total weekly fatalities to have settled on a seasonal nadir a little over 50,000. Instead, fatalities peaked at nearly 65,000 in April. Something was happening.

Absent the advent of the coronavirus phenomenon, what would total mortality have looked like to date in 2020? I would affirmatively suggest that the data can support the crafting of a benchmark against which one might contrast the recent and short experience of COVID-induced mortality. Specifically, I use the pre-COVID data to craft a benchmark that accommodates the seasonality of mortality processes and makes some accommodation for at least one dynamic aspect of the mortality process, population growth. The idea is that, so long as the profile of age and morbidity in the population is comparable for one year to the next, then total mortality should roughly track changes in population. As a rough approximation, such an assumption might be reasonable. I revisit this issue further below.

I crafted a benchmark based on a non-linear regression that accommodated seasonality in a mechanical way: it includes of sine wave. Accommodating a sine wave requires the inclusion of three variables, one each to accommodate a good fit for amplitude, frequency and a phase shift. The regression does not include any explicitly dynamic components. (It features no lagged variables or lagged error processes). It amounts to a purely descriptive exercise. But, does it fit the pre-COVID data well, and does it provide a plausible benchmark against which to contrast six months of COVID experience? I would suggest, yes.

I fit the following equation to weekly data for the weeks ending January 10, 2015 through November 7, 2020:

where t = week ending date and Population is indicated by year.

Given the scaling factor , one can expect the estimate of the frequency coefficient to be very close to 1. (The 99% confidence interval of the point estimate is [0.9925 – 1.0103].) The phase shift coefficient will indicate the phase shift enumerated in days. (It shifts the curve 56 days left of January 1, 2015. The curve thus hits inflection points roughly in early November and early May.) The term accommodates the prospect that the amplitude of the sine wave will increase as population increases. It captures a difference between maximum weekly mortality and minimum weekly mortality of about 8,000 in a given year.

I append the mortality benchmark to the following graph:

The benchmark does not capture spikes such as the spikes in January 2015, January 2017 or January 2018, but it does capture the seasonal trend, and it goes some way toward capturing population growth. The value of the benchmark, however, is in its contrast with actual mortality after the advent of COVID. The extent to which actual mortality exceeds the benchmark constitutes a measure of “excess mortality”. The 2017/18 cold-and-flu season featured an episode of excess mortality. (Excess mortality exceeded 33,000 in the three months December 2017 through February 2018.) The COVID experience has induced a more severe episode of excess mortality in 2020. In other words, the COVID experience really does appear to have induced mortality in excess of what one might have expected were 2020 to have proceeded unperturbed from its modest cold-and-flu season early in the year. But 2020 was perturbed, and that perturbation (COVID-19) shows up conspicuously in the data. Even so, COVID is not a great plague like the great plagues of the 14th or 17th centuries. Those actually great plagues could take away well more than half of a population over a sequence of a few years.

I note that the population that entered April 2020 may have been particularly susceptible to COVID. That population was coming off of a sequence of two mild cold-and-flu seasons. The population would thus enter April 2020 both older and sicker than a population that would have had to put up with harsher cold-and-flu seasons in 2018/19 and 2019/20. One would need access to richer data in order to craft controls for changes in the underlying susceptibility of the population to infectious disease from season to season. All of the results reported here thus depend on the assumption that populations from one year to the next are comparable. But, given the (likely) prospect that the population entering April 2020 was sicker than the populations of 2019 and (especially) 2018, the results will appear worse than they would otherwise have been. One could suggest that fuel for the fire had been building up for two years.

Conspicuous or not, the COVID phenomenon is not the great plague that journalists or even the experts in government would make it out to be. The gap between the benchmark and mortality during the COVID episode through November 7 represents 264,665 fatalities. Given it appears that 2020 was on track to be a mild year, one can reasonably argue that one can attribute all of those 264,665 fatalities, directly or indirectly, to the coronavirus experience. It turns out, however, that only 217,931 of those fatalities have been attributed directly to COVID. Another 46,734 in excess fatalities remain unaccounted for. It is numbers like this 46,734 that provide some basis for speculation that individuals and governments made adaptations that induced harm that compounded the COVID toll.

One can see these excess mortality numbers in the following graph:

This graph features total mortality and benchmark mortality (as above), but it also features total mortality less mortality attributed to COVID (Total Mortality less “Underlying” COVID). Note that there is a gap between the benchmark mortality and Total Mortality less “Underlying” COVID. That gap represents the 46,734 in excess fatalities not attributed to COVID. (Let’s call them “excess non-COVID fatalities”.)

What is going on? The CDC reports total mortality and mortality to which COVID is indicated as the “underlying” cause. With benchmark mortality in hand, one can then do some simple accounting and generate these three numbers:

Total Mortality in 2020 through November 7:

2,724,744 (A)

Total Mortality less “underlying” COVID:

2,506,813 (B)

Benchmark Mortality:

2,460,079 (C)

From these three numbers we can generate three differences:

Excess Morality:

264,665 (A – C)

Died by COVID:

217,931 (A – B)

Excess Non-COVID Mortality:

46,734 (B – C)

The numbers imply that COVID had a discernible effect; it is not the case that COVID fatalities supplanted fatalities that would have otherwise happened on a one-for-one basis. But has COVID displaced some fatalities, and, if so, did it displace a large volume of fatalities? Posed differently: Does most excess mortality indicate mortality that would have occurred absent COVID?

The numbers presented thus far do not provide a basis for anything but speculation, but the CDC data do offer a little more detail that we can use to frame, if not definitively answer, these questions. (More on that imminently.) But, note what else is going on in the graph. Non-COVID fatalities track the ebb and flow of COVID fatalities. Might that not strike one as strange or, at least, as surprising? Two rationalizations would seem obvious. First, some observers have suggested that COVID might indirectly induce non-COVID fatalities were people to forego the healthcare that they would regularly and otherwise secure. They might neglect to secure care, because healthcare providers had denied them care (in order to “flatten the curve” – that is, to preserve capacity to accommodate a prospective surge in demands for COVID care), or they themselves might have been too afraid to venture out of the house to healthcare facilities to secure care. Another rationalization would be that many of these non-COVID fatalities were actually “with COVID”. Specifically, individuals may have been infected; the extra immunological strain of the infection may have aggravated other conditions; actual COVID infections may have ultimately contributed to many fatalities without being identified as the principal, “underlying” cause of fatality.

One way to impose some structure on the question of how many fatalities were displaced by COVID would be to look at the frequencies of other modes of “underlying” causes of fatality. Evidence that certain modes of fatality appear under-represented in 2020 would be consistent with the COVID toll having subsumed fatalities that would have occurred even in the absence of COVID. At the same time, evidence that certain modes of fatality appear over-represented in 2020 could invite a few interpretations: Again, COVID may have aggravated certain pre-existing conditions and contributed to mortality; people may have failed to secure care that they would otherwise have secured; institutional responses to COVID (lockdowns and such) may have induced a host of fatalities that would have otherwise occurred. I will suggest that the CDC data exhibit patterns consistent with each of these three hypotheses.

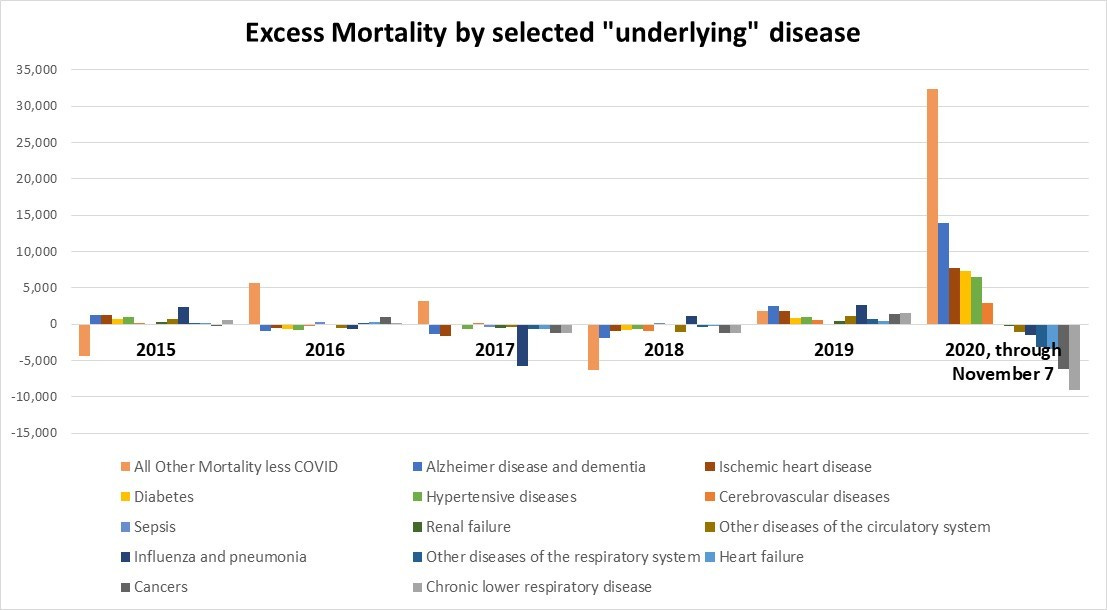

I examine many of the disease categories that the CDC data indicate as the most prominent “underlying” modes of fatality. (See the following graph.) No surprise these modes comprise the conditions that generally befall the elderly and the immunosuppressed. These categories include a host of (mostly circulatory) conditions associated with obesity. These include hypertension, ischemic heart disease (hardening of the arteries that sustain the heart), and diabetes. Other prominent categories include Alzheimer’s disease and dementia (aggregated together), cancers (malignant tumors), and respiratory conditions. Respiratory conditions include influenza and pneumonia (aggregated) as well as Chronic lower respiratory disease. I also account for all fatalities not assigned to a disease category. I aggregate all such fatalities in All Other Mortality less COVID. I also include COVID-19 in the graph.

COVID aside, a striking feature of these disease categories is that they all feature seasonality, and each trajectory features the same seasonality. Even cancers and “All Other” exhibit the same seasonality. Fatalities generally peak in January, and the living is easy in August. Note, however, that Alzheimer disease & dementia as well Ischemic heart disease track the COVID peaks in both April and August. The living might normally be easy in August, but not in 2020. People were succumbing to heart conditions and dementia just as the country was experiencing its “second wave” of COVID fatalities. People were also more likely to succumb to certain cardiovascular conditions and dementia during the first wave of COVID fatalities in April. Meanwhile, COVID fatalities seem to be undulating around the same level as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

I now apply the benchmark regression individually to many of the disease categories. I generate benchmark mortality for those same disease categories and then calculate excess mortality for each disease category. Consider Ischemic heart disease in the next graph:

The seasonality of fatalities attributed to ischemic heart disease is easier to see. The fact that ischemic heart disease spikes at same time COVID spikes in April is also obvious. Why might this be? One reason would be a tight connection between obesity and COVID. Specifically, researchers have identified a likely molecular mechanism that links the two. Adipose tissue supports fat cells. It also supports a high concentration of ACE2 receptors (angiotensin converting enzyme 2). Meanwhile, “ACE2 has been shown to be the putative receptor for the entry of COVID-19 into host cells.”[1] People who support a lot of ACE2 receptors are more likely to suffer severe effects from an infection that a slimmer person would have been more likely to shake off.

So, note the health analyst’s problem. If there really is a tight correlation between COVID and ischemic heart disease (by way of the ACE2 mechanism), should the analyst attribute a given fatality to COVID or to ischemic heart disease? About 7,800 excess fatalities attributed to ischemic heart disease obtain in 2020. Should most or all of those excess fatalities have been attributed to COVID? Or, as may have been the case, had COVID been indicated as one of some number of contributing factors? The CDC would know, but the publicly available data do not provide insight.

One could reasonably ask whether or not 7,800 excess fatalities attributed to ischemic heart disease is exceptional. Is 7,800 a high number? Further below I will suggest that it is. But, for now, consider All Other Mortality less COVID in the following graph:

All Other Mortality does not exhibit the same ostentatious peak in April 2020 that COVID or even ischemic heart disease does, but it does go on to generate a large volume of excess mortality, especially in the summer months. Indeed, through November 7, excess All Other Mortality exceeds 32,000 in 2020 – an exceptionally high toll.

In the next graph, we examine excess mortality by disease categories by year over the last several years.

As noted, excess All Other Mortality exceeds 32,000 in 2020. Excess Alzheimer’s disease and dementia is also conspicuous in 2020. It totals very nearly 14,000. Then there is a cluster of obesity-related conditions: ischemic heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension. Collectively, they account for about 22,000 excess fatalities. Then there is the matter of diseases that conspicuously disappear in 2020. There are 9,000 “too few” fatalities attributed to Chronic lower respiratory disease in 2020. Also, over 6,000 cancers disappear.

The 15,000-plus missing cases of cancer and chronic lower respiratory disease may have been folded in to the toll of COVID fatalities. I would suggest that such “missing cases” comprise good candidates for fatalities that would have occurred in 2020 even in the absence of COVID-19. At the same time, however, the 22,000-plus cases of obesity-related fatalities comprise good candidates for fatalities that might very well have been attributed to COVID. The matter of conspicuously excess fatalities attributed to Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and All Other is different. They are less likely to have been influenced directly by COVID but, rather, comprise good candidates for fatalities in 2020 that could have been avoided but for poor institutional responses to COVID. The excess fatalities from Alzheimer’s disease and dementia may have derived from the abandonment and isolation of elderly people in nursing homes. The excess of All Other Mortality may involve younger people who had been pushed over the edge by the lockdowns.

The may-have-this and the may-have-that simply reflects that the publicly-available data do not afford finely-tuned tests of policy-relevant hypotheses. Those hypotheses would include:

(1) All Other Mortality features a younger profile of people, and those people were more likely working in industries most effected by lockdowns. Those industries would include hospitality services.

(2) The obesity-related fatalities really did involve people for whom obesity was a prominent risk factor for COVID-19 infection.

(3) The “missing” cancer cases and cases of chronic lower respiratory disease did involve COVID infections even though such infections had not been indicated as the underlying cause of mortality.

The CDC sits on top of the data that could enable one to test these hypotheses.

Discussion –

Coming in to this exercise I was open to the idea that COVID fatalities were largely displacing fatalities that would have occurred absent the advent of COVID in 2020. That is the kind of proposition that Dr. Briand has advanced in her own analysis of the CDC data. Evidence that total mortality in 2020 had not appreciably increased would be abundantly consistent with that proposition. To explore this proposition, one would have to craft a counterfactual: How many people would have died absent the emergence of COVID? I crafted a benchmark of weekly mortality. The difference between the benchmark and actual mortality constitutes a measure of “excess mortality”.

It is hard to not conclude that COVID has induced excess mortality in 2020, but its effects are far more complex than a straight count of COVID fatalities would suggest. While the CDC attributes nearly 215,000 fatalities directly to COVID (through November 7, 2020), it is not immediately obvious that one can attribute all of that toll to excess mortality. Patterns in the data are consistent with the proposition that more than 15,000 in the COVID toll would likely have succumbed to various cancers or chronic lower respiratory disease in 2020 in the absence of COVID. At the same time however, one could potentially add to the COVID toll as many as 22,000 whose obesity-related conditions may have been aggravated by COVID infections. But, even some large of share of these people may have perished in 2020 absent COVID. They were not healthy. A real tragedy, however, appears to be the conspicuous excess mortality derived from Alzheimer’s disease and “All Other” mortality. Altogether, these 46,000 fatalities may have been avoidable but for the coarseness and crudeness of policy responses to COVID. Admittedly, the excess fatalities attributed to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia involve people who were likely not long for this world, but the toll does raise questions about the management of elder care. Meanwhile, the toll of “All Other Mortality” will have swept up a younger crowd of people who will have been denied many years, perhaps decades, of life.

The COVID phenomenon may be abundantly discernible in the “big picture”, but the big picture encompasses far more action than COVID alone can account for. Each week that about 58,000 +/- 4,000 people perish in the United States. That is like a Vietnam war – every week. We do not fetishize each of the 58,000 fatalities. We have only been fetishizing the COVID fatalities. A problem with fetishizing COVID is that it creates demand for government to “Do Something!”, but it is not obvious that government intervention itself has not induced more harm than benefit. Meanwhile, questions about the extent of the mis-management of elder care (if any) merely underscores the fact that our collective understanding of the COVID phenomenon remains poor. Characterizing the trajectory of the disease is hard enough, especially where there are competing political demands to both credit and dis-credit government interventions. The disease will diminish and may even disappear on its own accord with or without the application of vaccines. As it naturally diminishes, governments will demand some measure of undue credit.

One reason the disease will naturally diminish is that the population entering 2021 is likely healthier than the population that entered 2020. COVID fatalities may still go through some undulations, but they will fade. Excess mortality may even be discernibly negative in 2021. Such a result would be consistent with (a) COVID having concentrated its toll on the most immunosuppressed (and, thus, vulnerable) part of the population in 2020 – we can likely agree that that is true – and (b) an appreciable share of that most vulnerable population may have lived to see 2021, but not much longer. Such a forecast would seem to be sharply contrary to the expectations that the chief of the CDC, Robert Redfield, had been intent on instilling in us. In a presentation hosted by the US Chamber of Commerce on December 2, the CDC chief averred, “The reality is December and January and February are going to be rough times. I actually believe they’re going to be the most difficult in the public health history of this nation, largely because of the stress that’s going to be put on our healthcare system.”.[1] (Emphasis is my own.) But the country has seen more severe strains imposed on less capable healthcare systems: Spanish Flu 1918? Asian Flu 1958? Hong Kong Flu 1969? And what of the perennial scourge of measles and polio and outbreaks of small pox? What of the scourge of malaria, which had been endemic all over the country into the early 20th century? The CDC’s original mission, in fact, was to mitigate malaria. The director should use more measured language instead of pushing the rhetoric to 11. Are there no adults anywhere?

Data Sources –

https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Weekly-Counts-of-Deaths-by-State-and-Select-Causes/muzy-jte6

https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Weekly-counts-of-death-by-jurisdiction-and-cause-o/u6jv-9ijr

https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Weekly-counts-of-deaths-by-jurisdiction-and-age-gr/y5bj-9g5w

https://www.census.gov/

https://www.epicentro.iss.it/en/coronavirus/bollettino/Report-COVID-2019_16_december_2020.pdf

[1] “Risk of COVID-19 for Patients with Obesity,” Obesity Reviews, March 31, 2020 accessed at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/obr.13034.

[1] As of December 16, 2020: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/en/coronavirus/bollettino/Report-COVID-2019_16_december_2020.pdf