The Conceit of the Surveillance-and-Vaccination Paradigm

If a bird gets the flu and nobody notices, is the world better off?

There are mixed messages coming out of the new Trump Administration with respect to “bird flu.” The default position of the Department of Agriculture (USDA) since at least 2022 has been to wage jihad on “bird flu” by means of the mass culling of commercial, egg-laying hens and by the vaccination of those same hens. The new Secretary of the USDA seems to support continuing such initiatives. Is this kind of thing really not qualitatively different than the COVID dysfunction?

Meanwhile, there are some suggestions that the new Administration may not be fully committed to the mass culling of hens. (The matter of vaccination is still open.) Yet, a bigger question might be: If no one knew to look for bird flu, would no one have discovered it, and would no one have noticed any effects, anyway? Basically, “you can’t manage what you can’t measure,” but can we fool ourselves into measuring stuff not worth managing and then fool ourselves into managing it?

Much Ado About the Retail Price of Eggs

Last week or so, leading Democrats put out identically-scripted videos decrying the apparent fact that retail prices—and, most notably, egg prices—had not fallen since Trump’s inauguration in late January. This matters, they claim, because Trump had claimed he would bring the prices of eggs down on “Day One,” but “That Shit Ain’t True,” these great wits exclaim. Here we are on Day Fifty or so, and prices had not come down. Or maybe they have only now started to come down but only after having continued to go up after the inauguration.

Whenever retail prices of everyday goods go up sharply, some politician out there will likely toss out claims about “price gouging” or “price fixing” or “collusion” or “monopoly” or something. And, sometimes, the antitrust authorities get calls to look into it.

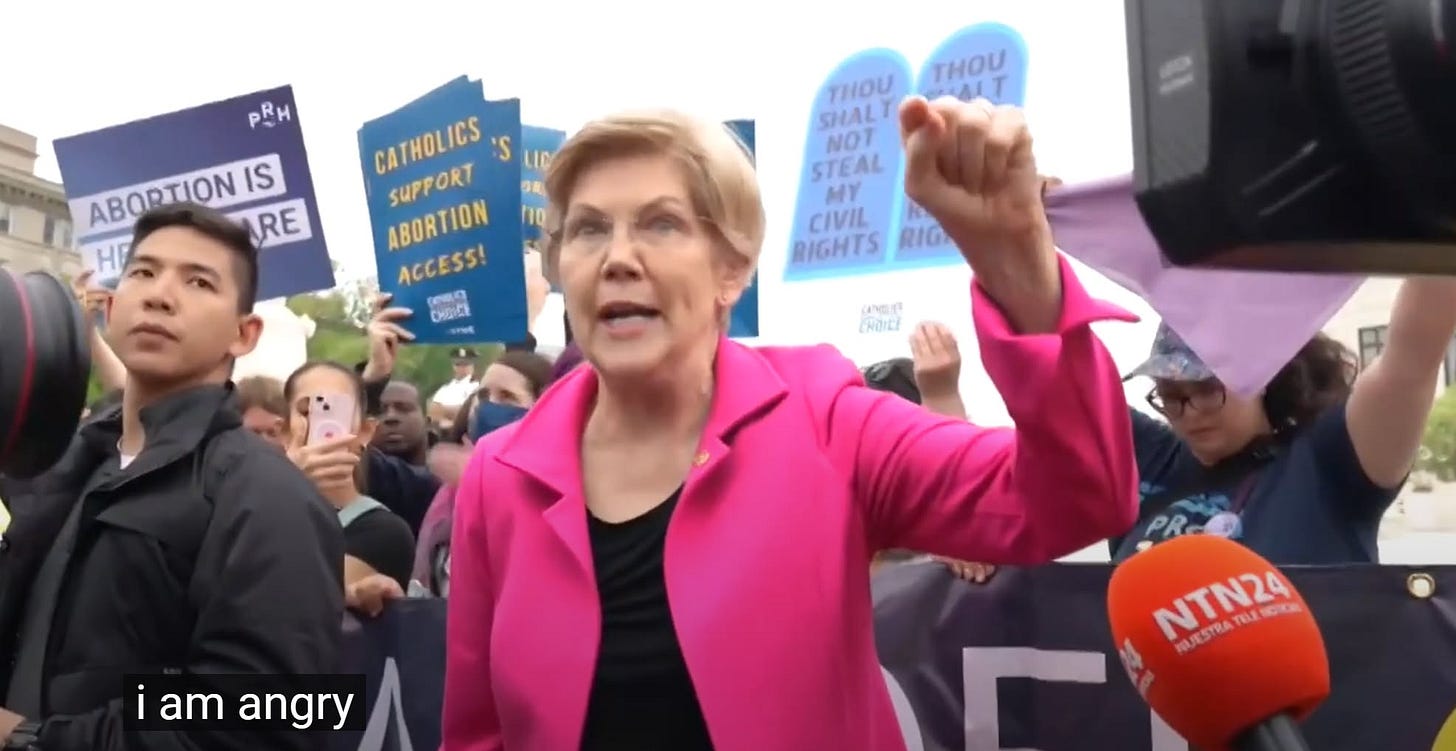

I’ve seen this kind of thing myself (during my time at the Antitrust Division) with respect gasoline prices. Meanwhile, over the last week or so, Elizabeth Warren, Senator from Massachusetts, has called on the antitrust authorities to look into egg prices. (In the Senator’s own words, “Warren, McGovern, Lawmakers Blast Trump’s Inaction on High Egg Prices.”) And there are reports that the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice will do just that.

I can only imagine what my former colleagues are thinking: The fact that the Department of Agriculture has been waging jihad on “bird flu” since at least 2022 might have something to do with increasing egg prices; more than 100 million hens have been culled in an effort to “stamp out” bird flu; reducing production capacity by destroying 100 million-plus hens might have something to do with the price rise; collusion may have nothing to do with it.

That all sounds abundantly plausible, but there are things to look into, and, at the very least, one can do some simple research to frame the issue.

So, what do we know? Americans consume about 100 billion eggs a year. Commercial producers host about 340 million hens at any given time during the year. (That makes for about one egg-laying hen for each person.) A commercial hen remains in circulation for about a year-and-a-half. So, in a steady state, about two-thirds of those 340 million hens—let’s call it 225 million hens—get culled through the course of a year.

Now, given well more than 200 million hens are regularly being culled in a given year, does submitting 150 million hens (say) over the course of three years to a bird flu cull really complicate the business of producing eggs? In a given year, some number of those culled hens would have been culled through the normal course of business. So, does requiring the cull of, say, 50 million hens in a given year as a bird flu measure severely mess up the logistics of egg production?

Some other questions: What does the bird flu-inspired culling of hens look like over space and time? Is such culling regionally concentrated at any given time, and is such culling episodic? And, how far does an egg travel from a given commercial chicken coop to market? So, if the USDA marches in and demands a sudden culling of 30 million hens in California, does that inspire producers in North Carolina to divert some volume of production further west to retail markets that would otherwise have been served by those California producers? Alternatively, could California producers quickly restore those 30 million hens?

In any case, this business about “collusion” could be interesting, because orthodox, textbook economic theory (“Bertrand-Edgeworth competition”) suggests that sweeping in and episodically demanding the destruction of production capacity could temporarily invest producers with monopoly power—through no doing of their own!

Bertrand-Edgeworth competition (BE competition) broadly suggests three kinds of outcomes:

(1) Severe competition: Producers each maintain a lot of production capacity, in which case any one of them is situated to dump more produce on the market and may perceive private advantages to doing just that. But, all together, producers ending flooding the market with output and driving prices down.

Now, producers would love to avoid this situation in which they each maintain what basically amounts to excess capacity. So, why don’t they each independently cut back on capacity? Granted, any one producer would be happy to see other producers cut back on capacity (while that producer itself does not cut back on capacity), so getting everyone in the industry to cut back may be difficult. If there were any dimension of competition to collude over, it may not be price or output per se but rather production capacity: You get this much capacity, you get that much, I get this much, and if we stick together, we find ourselves each operating at capacity. We thus end up committing to restricting output and realizing higher prices.

That all sounds great, but it might be hard to police a commitment to restrict capacity. I don’t know, but BE competition does contemplate the idea of restricted capacity:

(2) System-wide monopoly: System-wide capacity is so strained that each, individual producer ends up operating effectively as a monopolist. Indeed, capacity may be so strained, that producers even end up charging prices higher than an unconstrained monopolist would actually charge.

Basically, when capacity constraints bind, they should bind market-wide. All producers end up looking like monopolists.

Seasonal Monopoly?

Now, we can imagine markets in which demand for output is seasonal. Basically, do people tend to consume a lot more eggs during certain times of the year? One can imagine, for example, that people tend to do a lot more baking during the holiday season. (Historically, this has been true. Flour mills know it.) Does a seasonal peak in baking induce a seasonal peak in the demand for eggs? If so, we can imagine times of the year in which producers find themselves with excess capacity and bidding prices down, and we can imagine times of the year in which capacity constraints bind across all producers in a given, regional (or national?) market, and they all get to enjoy monopolistic profits—temporarily.

Then there’s the middle case. The first two cases are easier to explain: there is an obvious static “equilibrium” in either case: either everyone is a de facto monopolist or everyone is locked into supreme competition with each other. But:

(3) “Edgeworth Cycles”: Market-wide capacity is not entirely constrained but is situated somewhere just short of entirely constrained. There isn’t any obvious static equilibrium in that one producer’s decision to hold its production short of its capacity may induce another to expand output to its capacity. But, then other producer may perceive short-term advantage to expanding output, which can mess up the calculus of the producer that had originally expanded production.

It's this last bit of BE competition that inspired later theory about “Edgeworth Cycles,” and that stuff ties into an even larger body of theory about how to sustain collusion—as well as about how hard it can be to sustain collusion. Indeed, there are people out there who have extracted prodigious streams of consulting fees by carrying on about periodic episodes of “price wars” in markets for things like retail gasoline. These apparent “price wars,” they observe, may not reflect breakdowns in collusion but rather may reflect day-to-day competition. On any given day, prices may become unstable and fall as certain retailers endeavor to enjoy a very short-lived advantage.

In other words, “anything can happen,” which makes it difficult to build an affirmative case about “price-fixing” or “collusion”. So, what’s an antitrust authority to do? I can imagine the authorities being able to demonstrate that retail prices really do tend to go up when the supply-side gets strained and constraints bind. And prices might relax when constraints become lax. More pointedly, one can imagine the Antitrust Division looking back at earlier experiences with negative shocks to production capacity. Have there been other episodes when the USDA marched in and demanded destruction of tens-of-millions of hens? Have there been industrial accidents (fires at large processing facilities, say) that may have destroyed production capacity? Did retail prices end up rising in response to these negative shocks to production capacity? If so, were perturbations in prices more regional, or were perturbations in prices discernible nation-wide?

Industrial accidents could be interesting in that the numbers of hens that perish in such accidents may be on the order of hundreds-of-thousands instead of, say, tens-of-millions, but destruction of physical plant could prove especially disruptive. (I don’t know.) Replenishing stocks of hens may be easier and faster to do than rebuilding processing facilities.

Patterns in pricing consistent with capacity constraints binding and then becoming lax would be consistent with competition, and one would struggle to discern patterns more suggestive of collusion. Indeed, collusion, if any, might be such a 2nd-order affair that it might be impossible to discern. And what would collusion look like? Like an agreement among producers to install a little less production capacity than they otherwise might? And that lessened capacity would induce capacity constraints to bind a little more often through the course of a year? A fine story, but it’s too fine to see in the data, I am sure.

Meanwhile, our autistic federal government remains fixated on “vaccines”.

Specifically,

“USDA will be hyper-focused on a targeted and thoughtful strategy for potential new generation vaccines, therapeutics, and other innovative solutions to minimize depopulation of egg laying chickens along with increased bio-surveillance and other innovative solutions targeted at egg laying chickens in and around outbreaks. Up to a $100 million investment will be available for innovation in this area.”

I admit disappointment. The USDA seems to remain committed to a technocratic conceit that we can surveil the environment, identify hazards, and implement prophylactic measure that would include vaccination campaigns (mRNA therapies?). Surveil and vaccinate. What could go wrong?

If no one knew to look for “bird flu,” would anyone notice? There’s that Peter Drucker one-liner that goes something to the effect of, “You can’t manage what you don’t measure.” So, in other words, we should endeavor to bring good data to problems. We can then figure out how to manage them in a more informed way. Which sounds great, but when does seeking data, measuring stuff and then managing it degenerate into Robert McNamara’s “management by the numbers”? McNamara, recall, was infamous for measuring success in the war in Vietnam by “body counts.” The higher the body counts, the more winning! “Body counts” stood in as a “summary statistic,” meaning, one didn’t have to distract oneself with other analysis. Just count bodies.

Under the management-by-the-numbers paradigm, we may end up managing stuff for which we have available metrics rather than trying to sort out what actually constitutes a problem worth thinking about. Is “bird flu,” like COVID, another manufactured non-crisis? And, I submit that that was what COVID was. Even by March 2020 (early on), the Higher Institute of Health in Italy publicly reported that the median age of fatalities attributed to COVID exceeded the median age of plain old death. (I first read about this in Bloomberg, so this wasn’t some datum hidden way from English-reading audiences.) COVID really was like a bad flu in that it concentrated its toll on the immuno-compromised… who tend to be the oldest among us. Harsh but true. And, yet, governments hyped COVID and have since hyped their responses to it as a way of further hyping continued “surveillance” and “vaccination” of viruses that, if left alone, may constitute modest hazards, but if actively managed, might actually turn into serious hazards.

I hope that, under RFK Jr.’s leadership at Health and Human Services and under the new leadership at the Department of Agriculture, our federal health officials will make some progress sorting out better “vaccine” policies. Do we really know what we are doing? Have we placed too much confidence in this surveillance-and-vaccination paradigm over the decades, and could we not develop more evidence that the paradigm works—or doesn’t entirely work and may exacerbate health hazards?