The Dream of Nuclear-free, Net-Zero Nirvana

A predicted and predictable nightmare is unfolding in Central Europe as the cold season approaches.

This essay was motivated by a graph and by an absurd story.

First, the story. By the beginning of 2018, Poland committed to building a pipeline (Baltic Pipe) that would hook up with an existing pipeline in the North Sea (Europipe II) as indicated on this map. Baltic Pipe would transfer natural gas from Norway via Denmark to sites in Poland. In June of last year (2021), Denmark suspended permits for the pipeline, “citing the need to assess if the project would harm the habitats of certain mice and bat species.” The Associated Press reported:

The Danish Environmental and Food Appeals Board announced Thursday that it had repealed a land permit issued in 2019 for Baltic Pipe.

According to the appeals board, a permit for the project given by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency did not sufficiently lay out the measures that would be taken to protect dormice, Nordic birch mice and bats during construction of the 210-kilometer (130-mile) pipeline across Denmark.

The decision means that Denmark’s environmental agency will need to carry out more studies.

After some months of further study, Denmark restored the permits. Poland expects that Baltic Pipe will be in service by October. It might then start building up stocks of natural gas going into the cold season. And nary too soon, because Germany has long set itself up as the principal European hub of Russian gas distribution, but with Russia having throttled back gas supplies, the Germans and the Central Europeans may find themselves short of gas this next winter.

Two questions. First, what was Denmark doing? The European Commission had ordered Poland to halt operations at its Turow open-pit coal mine right on borders with both the Czech Republic and Germany. Was Denmark operating as an agent of the European Commission? In doing so, was it holding up Baltic Pipe in order to induce Poland to give way on the Turow coal mine? More generally, has the Commission been intent on compelling Poland to adopt energy policies that are more in the spirit of Germany’s Energiewende? Energiewende contemplates achieving “Net Zero” carbon emissions by making the transition from fossil fuels and carbon-free nuclear generation to a portfolio dominated by wind and solar.

Second, does Baltic Pipe actually make a difference in natural gas markets? One can imagine that Baltic Pipe would increase the capacity of Continental Europe to absorb natural gas from Norway, but note that Baltic Pipe merely taps in to a pipeline that already runs from Norway to Germany. (See this impressive map of North Sea pipelines courtesy of the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.) But, even if Baltic Pipe does increase delivery capacity from Norway, it does not increase the number of suppliers of natural gas. Thus, would Germany and Poland merely find themselves bidding up prices for that Norwegian gas? Ultimately, would Baltic Pipe enable Poland to reduce dependence on Russian gas, or will it end up where it has already been: negotiating with certain parties for access to Russian gas and negotiating with certain other parties for access to Norwegian gas? Baltic Pipe may enable Poland to cut out a German middleman from negotiations with respect to Norwegian gas, but would that make a difference?

To my knowledge, no sources in English, German, or Polish … or Norwegian or Danish, have advanced these questions or illuminated answers to these questions.

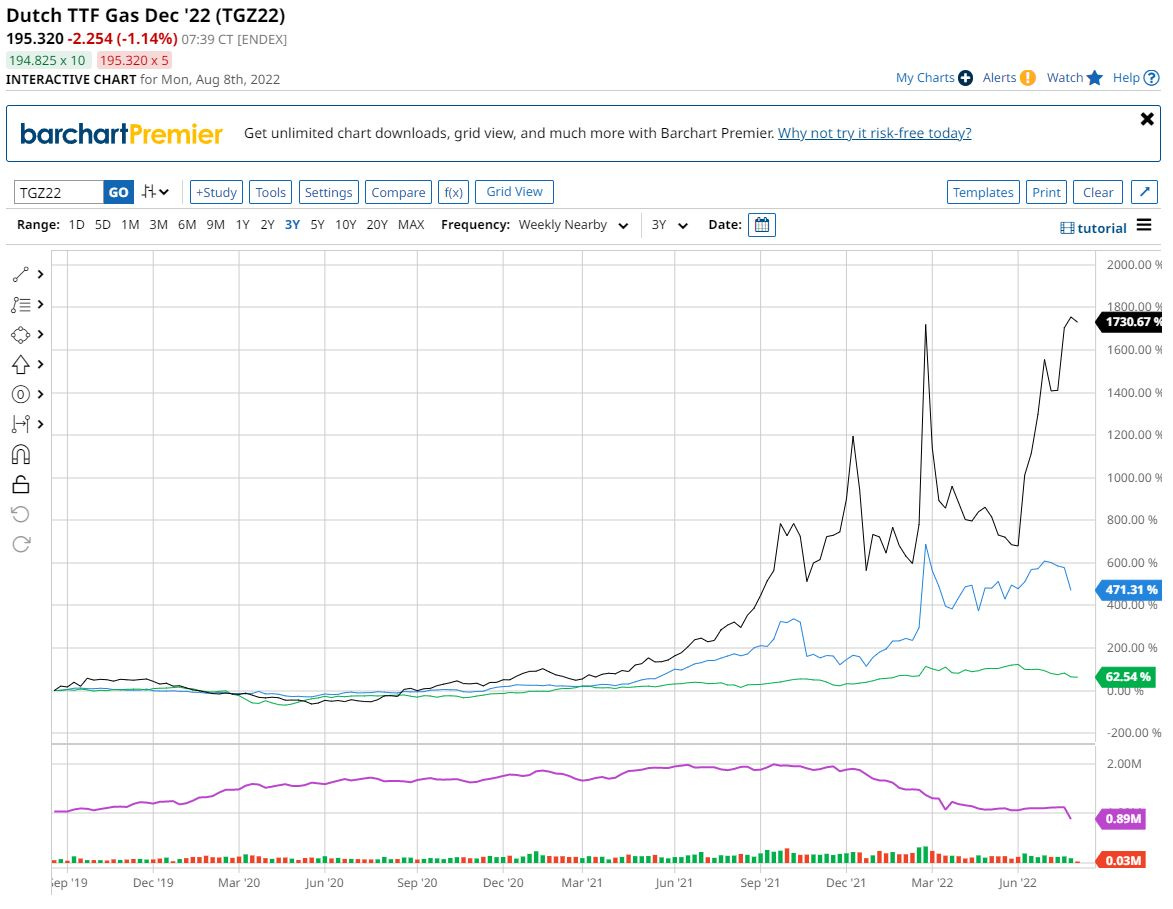

Now, on to the graph. By about March 2021, long before we got distracted with Ukraine, coal and natural gas prices in Europe started to assertively move higher. Oil prices had also started moving up, and, like coal and gas, they exhibited a sharp increase right after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, but oil prices have since moderated to pre-Ukraine levels whereas coal and gas remain elevated.

It may be politically expedient to blame everything on “Ukraine” or “Putin,” but processes bigger than Big Putin are at work. Germany’s long-running Energiewende policy would seem to have much to do with it. Efforts to impose Energiewende policy on Poland would seem to have something to do with it, too. But, ultimately, it is hard not to conclude that it is all in the service of a technocrat’s dream of securing a nuclear-free, Net Zero Nirvana.

In this graph, the black, blue and green lines indicate % changes from baseline prices of three years ago in prices for coal, natural gas, and oil, respectively. As of two weeks ago, coal is up 17 times the rate it had been going for three years ago. Natural gas is up nearly five-fold. Oil is up a little less than two-thirds.

Most of the action, obviously, has been in coal and in gas. The war in Ukraine seemed to have had some influence on oil prices, but, note that much of the action in coal and gas had already started more than one year ago, well before the war. Indeed, Ukraine may have been much in the news since 2014 when Russia took the Crimea and infiltrated the oblasti of Donetsk and Luhansk, but fuel prices do not obviously reflect that disruption. (The next graph goes back to 2012.) One might have expected some flux in gas prices after 2014, because Russia has supplied Ukraine with gas, and much of the gas that goes through Ukraine proceeds to Central Europe, but that gas has kept flowing.

The main question is: Why has there been so much action in coal and gas starting more than a year ago and comparatively little action involving oil?

The oil matter is easy to rationalize. The oil ecosystem really has long been globally integrated. Global shocks to supply or demand will influence prices, but, unless regional perturbations rise to the level of global shocks, then oil prices should remain nearly invariant to those perturbations. And what are the perturbations of interest? The United States tried to organize a boycott of Russian oil after the invasion of Ukraine in February. Much of the West did go along with a boycott, but most other buyers did not. So, the West might cut itself off from Russian oil, but it then finds itself securing supplies from other sellers. Russia ends up diverting oil to those other buyers. Those other buyers, in turn, end up sourcing less oil from those other sellers. Everyone reorients their sales and their supplies, and very nearly the same oil ends up on the global market. Oil gets re-routed, but global prices revert to what they might have been absent any artificially-induced re-routing.

Taken all together, the re-routing of oil probably involves higher delivery costs than would have otherwise obtained. If not, then we would have to ask why oil had not already been re-routed before the West had imposed its boycott on Russian oil. Either way, the fact that buyers and suppliers have adapted the routing of oil to the Western boycott illuminates a predictable and predicted result: Russia did not, ultimately, experience much more than transitory harm. The same goes for the West. Supplies might have become a little tight, but once everyone had settled on a new pattern of deliveries, prices settled down. Absent a boycott encompassing nearly all buyers, Russia ends up nearly as well off as it would have been. The same goes for buyers in the West. Everyone ends up with different dance partners and marginally higher delivery costs.

The mysterious case of coal and natural gas

Here is a puzzle: How did the Europeans end up facing sharply rising prices for coal and gas in 2021, a year before the business in Ukraine commandeered the headlines, at the same time that the Germans continued reducing demand for coal and gas? If demand in Europe declines and the same suppliers remain ready to service remaining demands, then should we not expect price to decline?

The beginnings of a formative answer might be that demands in Europe for coal and gas did not decline. Germany may have cut its demands, but it also may have ended up importing more electricity from other countries—and those other countries may have generated that imported electricity with coal and gas. Ultimately, European demands may not have changed that much. A mere reshuffling of deck chairs might explain prices not falling, but the puzzle still remains in that prices appreciated sharply. Something else was going on.

We can elaborate on our formative answer. It turns out that Germany retired three of six remaining nuclear generation facilities in 2021. Those six facilities had generated about 12% of actual generation in Germany in 2021, and those three retired facilities accounted for 50.0% of that outstanding capacity. So, nuclear generation may not have been dominant, but, would taking out that sizable margin of electricity generation capacity appreciably affect prices for alternative fuel sources?

Ultimately, my formative answer is this: Germany has been committed to Energiewende for years, and it remains to it even as Russia throttles gas supplies. It has demonstrated its commitment by shutting down 50% of its remaining nuclear generation capacity in 2021, and it remains committed to shutting the last of its nuclear generation capacity in 2022. This amounts to a non-trivial decline in the supply of electricity. Wind and solar had not been able to fill the gap in 2021 and surely will not fill the gap in 2022. Indeed, starting in 2021, electricity generators in Central Europe have looked to coal-fired and gas-fired generation to fill gaps in electricity generation. They started bidding up coal and gas prices a year before Ukraine started to dominate the news. At the same time, matters like the Turow affair suggest that the EU has been working to frustrate coal-fired generation. The EU may very well have also been working to frustrate gas-fired generation. All of these factors together—the shuttering of nuclear capacity, frustrating access to coal (and possibly to gas), the inadequacy of wind and solar—started in 2021 to impose great demands on remaining providers of coal-fired and gas-fired generation to fill anticipated gaps. They thus started bidding up prices for coal and gas. The end result?: Ironically, commitments like the Energiewende program to Net Zero carbon emissions may end up yielding higher emissions per unit of electricity generation (kWh) for some number of years and may even end up inducing an absolute increase in carbon emissions … absent a large decrease in total demand for electricity.

Admittedly, that all makes for a bit of an ambitious narrative, and note that one would not need to appeal to such an ambitious narrative were it the case that coal and natural gas prices had only been moving up since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Post-invasion, the Russians have used the pretext of pipeline maintenance (on the Nordstream I pipeline) to sharply throttle down gas deliveries to the West. More likely, the Russians are throttling gas deliveries in order to give the Germans and the Poles some indication of what they are in for in the winter unless they give up on sanctions. But, a question remains: Could not the Germans and the Poles substitute supplies from Russia with supplies from Norway? Possibly, and, yet, as a supplier of last resort, the Norwegians may find themselves situated to bid up prices. Thus, taken all together, one would not be surprised to observe a sustained rise in gas prices. And, insofar as coal can substitute for gas, then one might expect a rise in coal prices, too. Difficult it is, however, to rationalize a sustained rise in coal and gas prices in Europe starting an entire year before Russia invaded Ukraine. Hence the ambitious narrative.

Note, that the bit about Norway being a “supplier of last resort” is consistent with the idea that natural gas markets are regional. If gas markets were globalized, then Germany and Poland could find other suppliers. As with oil markets, one might observe some re-channeling of supplies; global supply might not appreciably change. But, global markets are not global by accident. They are global, because private parties and (possibly) public entities will have invested enormous resources in the logistics of getting stuff from one place to another at low cost. Markets for oil, for example, have long been globalized. And, they’ve been globalized, because a lot of parties have already invested resources in enabling oil from anywhere in the world to get to anywhere else in the world at low cost. Those supertankers are an engineering wonder. But they can get oil from, say, Ghana to China or to Germany at very low cost. Meanwhile, on the ground and on the seas floors, engineers have figured out how to extract oil at costs low enough to make it economical to get that oil on to that global market.

Markets for natural gas have a way to go before they become globalized—if ever. Building facilities to liquefy natural gas, to transport that liquified natural gas (LNG) and to receive that LNG, remain outstanding projects. On top of that, LNG is dangerous stuff. Indeed, the 2005 film Syriana (with George Clooney and Matt Damon) ends with an insurgent taking out a vessel dedicated to LNG transport. One can imagine the explosion of a vessel dedicated to LNG transport rivaling those of the ammonium nitrate blasts in Beirut (2020), Texas City, Texas (1947) or Brest, France (1947). One can imagine that LNG is costlier to handle than either crude oil or distillates (fuel oils).

But, still. What was going on with (regional) markets for coal and gas in Europe in the spring of 2021? Let’s take a look at more graphs.

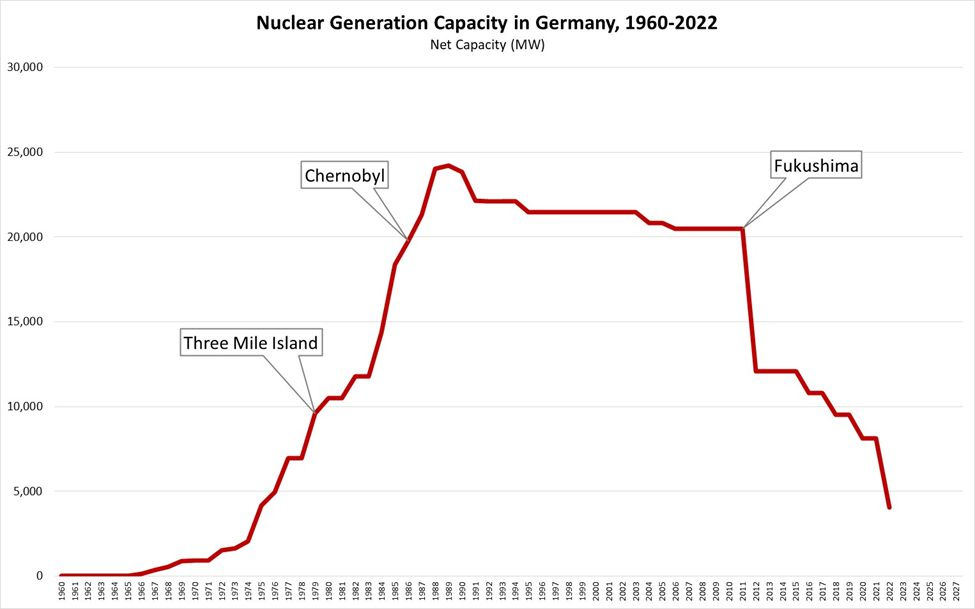

Sources: The International Atomic Energy Agency at https://pris.iaea.org/PRIS/CountryStatistics/CountryDetails.aspx?current=DE and https://cnpp.iaea.org/countryprofiles/Germany/Germany.htm.

This graph indicates nuclear generation capacity in Germany going back to the early 1960’s. The government of Angela Merkel promptly shuttered about 40% of Germany’s nuclear capacity right after the nuclear accident in Fukushima, Japan in 2011. One might even suggest that the Chernobyl experience in 1986 helped stall the advance of nuclear generation in the late 1980’s, although it is not obvious that the Three Mile Island incident in 1979 had much sustained effect, if any, on energy policy. One can see, however, that, post-Fukushima, Germany has assertively moved to retire all of its nuclear generation capacity. Germany remains committed to retiring the last of its nuclear capacity by the end of 2022.

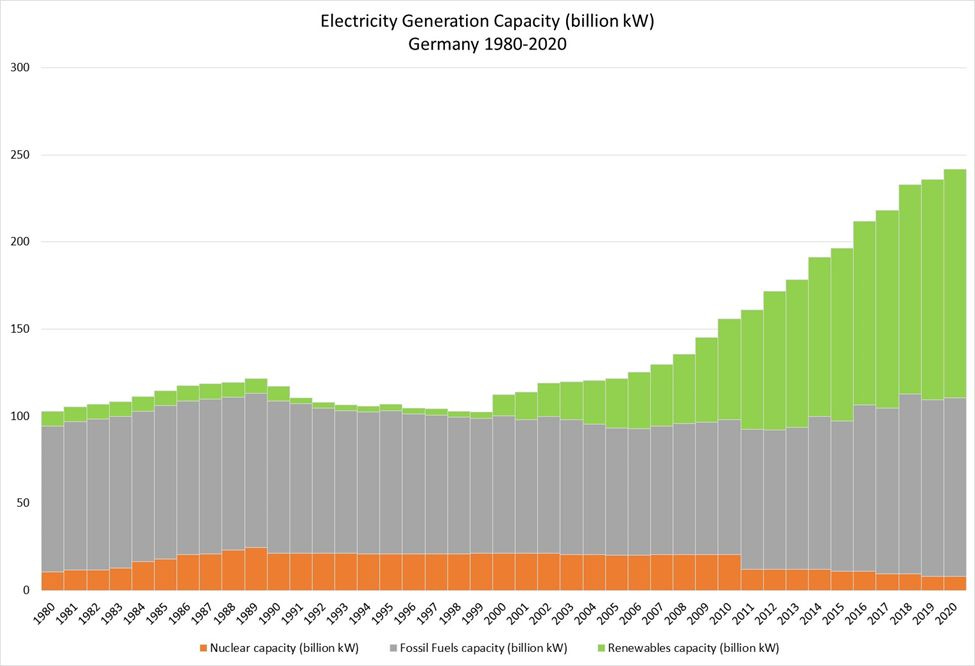

Let’s take a broader look at generation capacity in Germany:

Source: The US Energy Information Agency (EIA) at https://www.eia.gov/international/data/world/electricity/electricity-generation.

This graph indicates what amounts to name-plate capacity across three classes of generation: renewables (green), fossil fuels (grey) and nuclear (orange). Renewables (mostly wind and solar) have the appearance of more than filling gaps. But name-plate capacity is not the same thing as effective capacity, for, absent sun and wind, solar panels and windmills amount to zero productive capacity. Absent the Nirvana of cheap electricity storage capacity, wind and solar cannot reliably serve either “baseload” demands or peaking demands. Accordingly, how might one measure the effective capacity of wind and solar?

It is unfortunate that the EIA data do not extend beyond 2020, but they do indicate that Germany had been aggressively expanding generation capacity driven by renewables while also paring down nuclear capacity. But note that generation capacity fired by fossil fuels has also edged up since at least 2012. The aggressive expansion of renewables has not induced the retirement of capacity fired by fossil fuels. Why is that?

Let’s look at actual generation in Germany:

In this graph one can see that total generation of electricity and consumption of electricity have both declined over the last few years. Moreover, most of the decline in generation comes from capacity fired by fossil fuels. Renewables have actually generated increasing volumes of electricity. So, fossil fuel capacity has edged up, but actual fossil fuel generation has gone down sharply. That makes for a bit of a puzzle. Are concerns about the reliability of the grid motivating the authorities to expand capacity fired by fossil fuels? It looks like they are trying to maximize the use of renewables while holding fossil fuels in reserve to prevent the breakdown of the grid on windless or cloudy days.

Now, let’s look at Poland:

Poland has not maintained any nuclear capacity, but it has been expanding renewables capacity. Note also the big jump in fossil fuel capacity in 2017. The expansion of renewables has not obviously diminished the role of non-renewables. That said …

Actual generation via non-renewables has declined the last few years. Moreover, total consumption has exceeded total generation in those same years. No surprise, Poland has imported electricity to make up for the shortfall. The big surprise might be that Poland itself has not been a net exporter of electricity. Rather it stands more as a supplicant than a supplier.

Both Germany and Poland are supplicants in that their energy situations look tight the last few years. Total generation and consumption have declined in both countries while dependence on renewables has increased. The continued expansion of renewables has not led to energy abundance. The experiences in Poland and Germany the last few years may comprise evidence of strain across energy systems that span Central Europe. Coal and gas markets have been signaling strain since at least March 2021, a year before Russia had invaded Ukraine. The politics of war and sanctions have aggravated the energy problems that Poland, Germany and (likely) other countries in Central Europe already face. These countries now find themselves playing a Game of Chicken with Russia: Will they relent on economic sanctions (and be rewarded with gas supplies via the Nordstream I pipeline), or will they go into the cold season with inadequate stocks of coal and gas?

Then there is the dream of a nuclear-free and carbon-free Nirvana. Wind-driven generation and solar involve a host of under-appreciated environmental issues. Cadmium and other rare earth metals that go into solar panels poison the ground waters and rivers of China. Those same toxins in retired panels require disposal in hazardous waste dumps. But, wind and solar have long been blessed with the appearance of being environmentally friendly. That said, they are not enabling the Central Europeans to free themselves from both fossil fuels and nuclear energy. Something has to give. One thing that is giving is demand. People are cutting back on their energy demands, likely because they face higher energy prices as well as mandated cuts in supply at home and on the job. Other things that are giving are coal and gas. The system does not appear capable of supporting itself on unreliable and expensive renewables, and, with the authorities continuing to cut nuclear energy, we may yet see carbon emissions increase. What was the purpose of Energiewende?

This essay complements an earlier essay titled “Government-induced Energy Crisis.” That essay explored the conspicuous increase in coal prices in 2022 and went some way toward explaining the role of futures markets.

It begs the question: cockup or conspiracy? The green ideologues in power have revealed their true utopian colours and yet again the ends (going green) justify the means (demand destruction and the consequent plummet in standards of living). Years of demonizing fossil fuels and "ESG" nonsense has led to huge underinvestment in extractive industries and structural undersupply. Of course it is convenient to blame Mr. Putin for higher prices, and that is why the collective west led by the US pushed for this proxy war against Russia, which they will fight to the last Ukrainian. The goal has always been to destabilize Russia and ultimately balkanize the country in order to strip mine the resources as occurred during the "shock therapy" privatizations and liberalizations of the 90s. You only need to read some of the papers published by neocon think tank establishments who are driving policy in the Biden Whitehouse today. And today US LNG exporters are making money hand over fist, but so is Gazprom, who will probably never again fight for market share in the NWE gas market as they did before (they're not wanted there), but will rather maximize revenue via higher price (as a result of lower supply). Even if Europe were to roll back sanctions (which they should do immediately as they have quietly done with food, fertilizer and in shipping insurance) and give Russia guarantees that the NS1 compressors will not be subject to further sanctions, I am not sure the Russians would turn up the taps -- why should they, we are in a hybrid war with the Russians, whether you like it or not.... On Monday gas prices reached all time highs... The W22 contract is trading at 285 Eur... this represents a 12x rise. Meanwhile politicians such as Draghi say the following today:

*DRAGHI: ITALY CAN CUT RUSSIA GAS IMPORTS TO ZERO FROM FALL 2024

*DRAGHI: EU PLAN ON GAS PRICE CAP PRESENTED AT NEXT EU COUNCIL

So while looking to cut supply further, they also block the mechanism of demand rationing. The end goal is clear... this will be called "market failure" and we will be left with a centralized command and controlled economy run by technocrats and bureaucrats characterized by deficits and rationing. Welcome to the New World Order as imagined by the globalist elites....

Can these leaders be that clueless? Clearly the strategy was and is failing to provide energy.