Designer Western Declinism

Predictable, Predicted and Sponsored by the West Itself. But should we worry?

F.X. had spent appreciable time at the World Bank and then had risen up through the ranks of a big-name French bank. His great professional love, however, was not modern money and banking but rather money and banking in the Late Middle Ages. That is one reason that, 25 years ago, the two of us would find each other standing outside the State Archives of Venice each morning just before the 8:30 am opening. The other reason was that I myself was absorbed with financing in the Late Middle Ages. How did Venice finance commercial empire in the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries, all in the face of plague, war, crusade and piracy—to say nothing of day-to-day contracting hazards? How did people manage to make a ducat and pay the rent when operating in “conflict zones”?

We’d get in to the reading room at the archives, find our preferred seats and grind through medieval documents all day to the point of physical exhaustion. Six days a week. Who knew that staring at parchment could be so physically demanding? But we loved it.

My preferred seat was at a table that I knew from abundant experience would be shielded from direct sunlight through the entire day. The reading room was a long, vaulted hall that had been part of a monastery. At my seat I could examine documents by the diffuse, gentle, natural light coming off of the interior masonry.

We got to talking about China one morning. This was just before the 8:30 opening. “Imagine what China would be like if you could get a billion people to operate efficiently?” F.X. was not very sanguine about what China would be like. Here we are 25 years later. The Chinese authorities can shutdown protests by assigning people red, no-go status on a universal, state-mandated coronavirus app. Like Zeus zapping his enemies with thunderbolts from on high, the Chinese authorities can zap political undesirables at the flip of a switch, and they can do it en masse. F.X. was on to something. But just wait until the authorities (in China, in Canada, in the EU, in the United States) roll out Central Bank Digital Currencies. The authorities will be able to freeze any one of us out of daily commerce with the flip of a switch, because one bothered to show up at a protest. Just ask the de-banked Canadian truckers what that might be like.

It might have been during that same summer (1997) that I had made my first ever trip to Poland. My friend in Krakow introduced me to a few of his friends, two artists. They took us to one of their preferred hangouts, and it was there that I found myself being harangued by a Chinese fellow about the place of “human rights” relative to economic development. “In the countryside a man may only own a single pair of pants. Isn’t it a human right to own a pair of pants?”

I can’t remember how the topic came up, but I do know that pressing people I don’t know about human rights in their own country is not my thing. Indeed, pressing people I do know about human rights in their country is not something I’d do. The important thing here, however, is that the speaker was motivating the proposition that economic development should not be held hostage to political liberalization. Let China develop. The Chinese can then worry about political liberalization later.

There would be a lot to unpack there. First, there is the idea that political liberalization could frustrate economic development. The former should keep out of the way of the latter. Then there is the suggestion that the authorities, who had thus far maintained a monopoly over political power, would somehow acquiesce to political liberalization after some degree of economic development had been achieved. One-party rule would give way to competition between more than one party. And that would be a good thing, because ‘Our Democracy’. Something like that.

It is hard not to suggest that that last bit about how the authorities would acquiesce or would willingly organize political liberalization is rubbish. It’s just cheap rhetoric, a feint. There are examples of political monopoly giving way under pressure to political liberalization. But few may be the examples of political monopolists going out of their way to enable and craft the liberalization. Lord Byron held out George Washington, in explicit contrast to Napoleon, as one person who (after the American Revolution) could have stepped in to the role of monopolist but, like a “Cincinnatus of the West,” retreated from public office to his farm at Mt. Vernon. Washington left it others to take up the business of designing liberalized processes and then governing the new United States under the terms of those liberalized processes. King George III exclaimed that “If he does that [retreat like the mythical Cincinnatus to his farm], he will be the greatest man in the world.”

The military regime that governed South Korea from 1961 through 1988 was not heavily populated with Cincinnati of the East. Long story short: Park Chung Hee and his people staged a coup in 1961. Like Ukraine, the country had been in the thrall of a cluster of oligarchic families. The new regime tossed the oligarchs in prison before one of them argued (persuasively) that the new regime really would require the know-how of the oligarchs in order for the regime to implement its new economic program. The leadership agreed, but it basically made the oligarchs agents of its economic policies, and it did that mostly by taking over the entire financial sector and getting in to the business of “picking winners.” The government would determine which new, industrial projects would secure access to government-subsidized financing.

All well and good, it seems, in that South Korea shifted out of the stagnation of the 1950’s and into a regime of sustained economic growth. A middle class started to develop, but with that came demands for the regime to liberalize political competition. In 1980 the South Korean intelligence chief assassinated President Park, and that set off a mad scramble for power. The duo of Chun Doo Hwan and Noh Tae Woo cut a deal by which they would stage their own coup and install Chun as president. Staging the coup did involve suppressing a massive protest in the city of Kwangju. Official reports are that only about 200 protesters died. The reality seems to be that something in excess of 2,000 people died.

One thing that never died was the campaign to see that the new regime would assume responsibility for the “Kwangju Incident.” The new regime did preside over many years of double-digit growth, but that high growth started to give way to (still high) single-digit growth. And then the still-growing and sizable middle class started to exhibit some restlessness.

The how and why of it is all a little mysterious. But, perhaps it makes sense to understand the rise in demands for political liberalization not as a deterministic process but as more of a stochastic process. That is, the country might randomly end up on some trajectory that would yield liberalization sooner rather than later. Or not. But, we do know some of what happened along the actual trajectory: The perspicacious and opportunistic Noh Tae Woo “blamed” President Chun for the Kwangju Incident and committed to real constitutional reform. The regime really did commit to important reform. The reforms included new elections. Noh did win that first presidential election in 1988. Chun Doo Hwan did end up doing some time in prison.

Not long after serving his five-year term as president, Noh Tae Woo found himself serving a term in prison. Meanwhile, from the beginning, intra-party politics in South Korea, replete with the occasional brawl in the Parliament, proved to be very animated and competitive. The people got what they wanted (political liberalization) and have, like the rest of us, been complaining about electoral politics ever since. That is what democracy looks like.

South Korea and Pinochet’s Chile stand out as exemplars for the uneasy proposition that the Chinese fellow in Krakow might have been on to something. Here the idea might be that the regimes in South Korea and Chile may have been committed to political monopoly (their own monopoly), but they were also committed to certain classically liberal institutions. Most notably, they were committed to private property. The authorities might not have been too keen on maintaining certain civil rights and natural rights. They might not, for example, have been too keen on the “right of association”—basically, the right to freely talk politics and to organize protests. But they did commit to not expropriating people’s homes and businesses just because such people maintained inconvenient political views. The people could invest with security. And they did, albeit not necessarily with government-subsidized financing. They did it by scraping together whatever financing they could largely within informal networks of lenders—friends, family, neighbors. A sizable class of small-business people did emerge. These people, “the middle class,” came out in large numbers in South Korea in 1987 to protest against the regime.

Contrast the experience in South Korea with those of North Korea or Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe. North Korea and Zimbabwe stand in for the proposition in George Orwell’s 1984 that:

Power is not a means; it is an end. One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship. The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object of power is power.

I can recall being very puzzled by that passage when I had first read it as a very young person. Wouldn’t a dictator be interested, like anyone else, in enabling the economic development of his fiefdom? Would greater prosperity not translate into greater … power?

Power wielded by whom, one might ask? The ruling clique in North Korea seems intent on maintaining control, even if that means suppressing the emergence of a middle class. The same goes for Zimbabwe. Long story short: Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia) secured independence from Britain in 1980. Robert Mugabe became president following elections in that same year. The country had already established itself as important exporter of wheat, and that wheat mostly came out of efficient, mechanized farms—farms mostly owned and operated by white citizens.

One can imagine that that last point was a little inconvenient. But Mugabe seemed intent on maintaining the productivity of the agricultural sector. In a speech on Zimbabwe’s first day of formal independence, he seemed to suggest that the new regime would respect property rights, that it would not expropriate the farms and redistribute the lands to other (black) citizens of the newly-independent Zimbabwe. I remember reading in the Economist magazine about how some observers characterized Mugabe and his speech as “messianic.” Indeed, even now the terms “Mugabe” and “messianic” will yield quite a number of hits in any online search.

Alas, Mugabe’s messianism eventually gave way to opportunism. He may have been intent on preserving the productivity of Zimbabwe’s agricultural sector, but, when he perceived that veterans of the war of independence collectively posed a serious threat to his hold power, he and his regime finally committed to land redistribution. Some volume of rape and murder, replete with beheadings, was involved. Small, subsistence farms soon supplanted efficient, mechanized operations. Veterans sold their crusty AK-47’s for about $8 a piece and traded up to crusty, crude farm implements. The veterans found themselves too busy scratching out an subsistence existence to bother with distractions like political activism. Agricultural surplus dried up.

I observed this to someone who had been working for the United Nation’s food program (The World Food Programme), and that someone then lit up, realizing just then the coincidence of Zimbabwe’s land redistribution and the fact that the Food Programme had stopped procuring wheat from Zimbabwe. It suddenly became obvious.

So. Can the South Korean experience give us some ideas about what a Chinese experience could look like? The Chinese have had a Kwangju-like experience (the massacre in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989), but the regime survived that. China would also seem to have a burgeoning middle class, but the regime seems to be busy holding the middle class down—at least in Shanghai. Or, let’s look at things in stochastic terms: China flipped a coin in 1989. Things could have gone this way or that way. They did not go the way of broad, political liberalization. Rather, the ruling clique survived and went on to suppress certain inconvenient factions. But, if economic growth in China were to stall, might the Chinese regime find itself having to go through a new coin-flipping episode?

Or, are the experiences in North Korea and Zimbabwe illuminating? Specifically, might the ruling clique in China be willing to suppress the welfare of large constituencies (and of the country at large) in order to maintain its monopoly? Mao’s clique has done that before. The ruling clique in China seems to be doing that now. Note that the millions of Uighurs stuck in concentration camps in western China are not available for comment on this point. The upper-class denizens of Shanghai might also be difficult to reach for comment.

Alfred T. Mahan is most well-known for the book The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783 (1890). The basic point was that a country might develop sea power in order to maintain access to trade routes, geographically dispersed resources and foreign markets. Accordingly, it could make sense to occupy an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, little more than a deserted rock, if it could serve as a coaling station for merchant fleets and navies. A network of such sites would thus enable a nation to project power and influence over great distances.

Less well know might be Mahan’s mysterious tome The Problem of Asia (1900). Here much of the focus was on China and its seeming inability to integrate itself with a globalizing trade economy. Mahan then found himself taking up Imperial Russia’s efforts to expand its capacity to project power in the Pacific. Within a few years, Japan would do something about that, drawing Russia into an intendedly quick, sharp war by which it would expel the Russian fleet from the base that Russia had nabbed from China (Port Arthur, now Dalian on the Liaodong peninsula) as well as expel the Russians from Korea. The Japanese also worried about the Russian fleet at Vladivostok, “Lord of the East”.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1905 did turn out to be relatively short, and the Japanese did manage to achieve their objectives before very nearly having exhausted their limited resources. Mahan’s book did not explicitly anticipate conflict between Russia and Japan, but Mahan did hold out Japan as an example of what China failed to be: a country that had adapted itself to a modern, globalizing trade economy. He almost seems to suggest that Japan, Britain and the United States could expect to share common interests in the Western Pacific. If there were “problems” in Asia, they seemed to be motivated by Russian encroachment and Chinese recalcitrance.

One can puzzle over Mahan’s characterization of the problems in Asia, but one great tragedy he did not anticipate was the fact that Japan, Britain and the United States would eventually come to perceive their interests as competing, not common, in the Western Pacific. The Japanese leadership became concerned that the British and the Americans might constrain Japan’s access to the seaways, and, like the case in 1904, the Japanese hoped to induce a short, sharp war in 1941/42 along the way to securing a firm understanding with these other sea powers about the scale and scope of Japanese influence in the Far East. That whole venture, of course, merely resulted in a great tragedy, but ironically, Japan did end up in the post-war period with much of what it had been looking for: unhindered access to the commercial seaways.

By 1983 the Japanese prime minister, Yasuhiro Nakasone, would declare for the benefit of a Japanese audience the fact that “Japan had caught up with the West.” The Western press took note, and not without a hint of panic. From the estimation of Western journalists, Japan had transformed itself into “Japan, Inc.,” a mercantilistic, industrial powerhouse that supported companies that were outcompeting less efficient foreign entities and winning increasing shares of sales in foreign markets. Japan was something to be feared.

These same journalists missed Prime Minister Nakasone’s point. The bit about having “caught up to the West” was merely preamble to his larger point that Japan would be putting aside the kind of industrial policy that had served it so well in the post-war period—much the same kind of policy that the regime of Park Chung Hee had implemented in Korea post-1961. Instead, private enterprise would have to look to its own wits and resources going forward. The government was going to get out of the business of offering “administrative guidance” and preferred financing.

By Mahan’s estimation, Japan may have become what he had hoped it would become. By that same estimation, The Pacific War (1941-1945), was a tragic deviation from the trajectory to which Japan had ultimately returned. Japan would become a peer among peers. Those other nations might have the appearance of “declining” by virtue of the rise of another country (Japan), but that was all good and was to be encouraged.

It was at about the same time that Japan had “caught up” that “the West” had started to sponsor the rise of China. That effort picked up in the 1990’s, and even the industrial powerhouse of Japan started to experience “deindustrialization” (産業空洞化) or “hollowing out.” High labor costs in the West and Japan induced Western and Japanese enterprises to set up shop in places like Malaysia and Vietnam and, increasingly, China. Western Europe and the United States have since gone on to experience dramatic “hollowing out.” Formerly industrial economies have become increasing oriented around “gig” services and digitalized services.

“Hollowing out” makes the relative decline of the West and Japan—decline relative to China—appear a lot more like absolute decline. The hollowing out of certain types of post-industrial communities is obvious. What would Mahan think of that? He seemed to maintain a Smithian concept of the wealth of nations insofar as free trade would yield mutual gains. Was he not concerned that globalization in the early 20th century might induce a game of winners and losers according to which gains would be concentrated on the few (the winners) and losses would be concentrated on whole communities (the losers) less well situated to adapt? Would Mahan be appalled to see what globalization has wrought in such communities in its early 21st century incarnation?

Back, but back in Krakow in 1997 …

One of my new artist friends volunteered the idea that our Chinese friend was a spy… “Spy” struck me as a little strong, but the idea that the Chinese authorities might have been snooping around the Eastern Europe and Central Europe of the late 1990’s looking for investment opportunities might make for a good story. Private entities—Korean firms like Daewoo, for example—had been doing much the same. The Eastern Bloc had managed to hollow itself out absent any help from the West or from China. Here were all these idled factories and idled factory workers. Setting up assembly plants and distribution in Central and Eastern Europe—even setting up manufacturing facilities—could make sense.

What I do know is that Chinese personnel had been snooping around Ukraine before the coronavirus phenomenon emerged. They had been looking to acquire aerospace entities. A non-trivial volume of Soviet aerospace capacity and know-how had been concentrated around Kharkiv, Ukraine, near the border with Russia, and it has persisted to this day… or, at least until the Russians started lobbing shells into Kharkiv in February. The prospect of the Chinese absorbing these entities was a matter that even the Keystone Kops who populated the ranks of American officials in Kiev picked up on.

My new Polish friend did volunteer the idea that she’d rather live under the (then still existing) American imperium than under the emerging Chinese imperium. I still puzzle about what imperium, American or Chinese, means, but people in countries absorbed in China’s Belt-and-Road initiative might have ideas about Chinese imperium. Better, perhaps, it might be to inquire with the locked-down residents of Shanghai.

Meanwhile, Chinese imperium is emerging. But, that was part of the plan, right? And was that not supposed to be, on net, a good thing? After all, if we are going to encourage countries to develop, then should we be surprised when they do develop and end up wielding greater economic power? Did we not sponsor China’s rise, replete with entry into the WTO and most-favored-nations trade status in the United States, as part of a larger vision of securing the end of history wrapped up in gilded packaging as the final, glorious triumph of globalization?

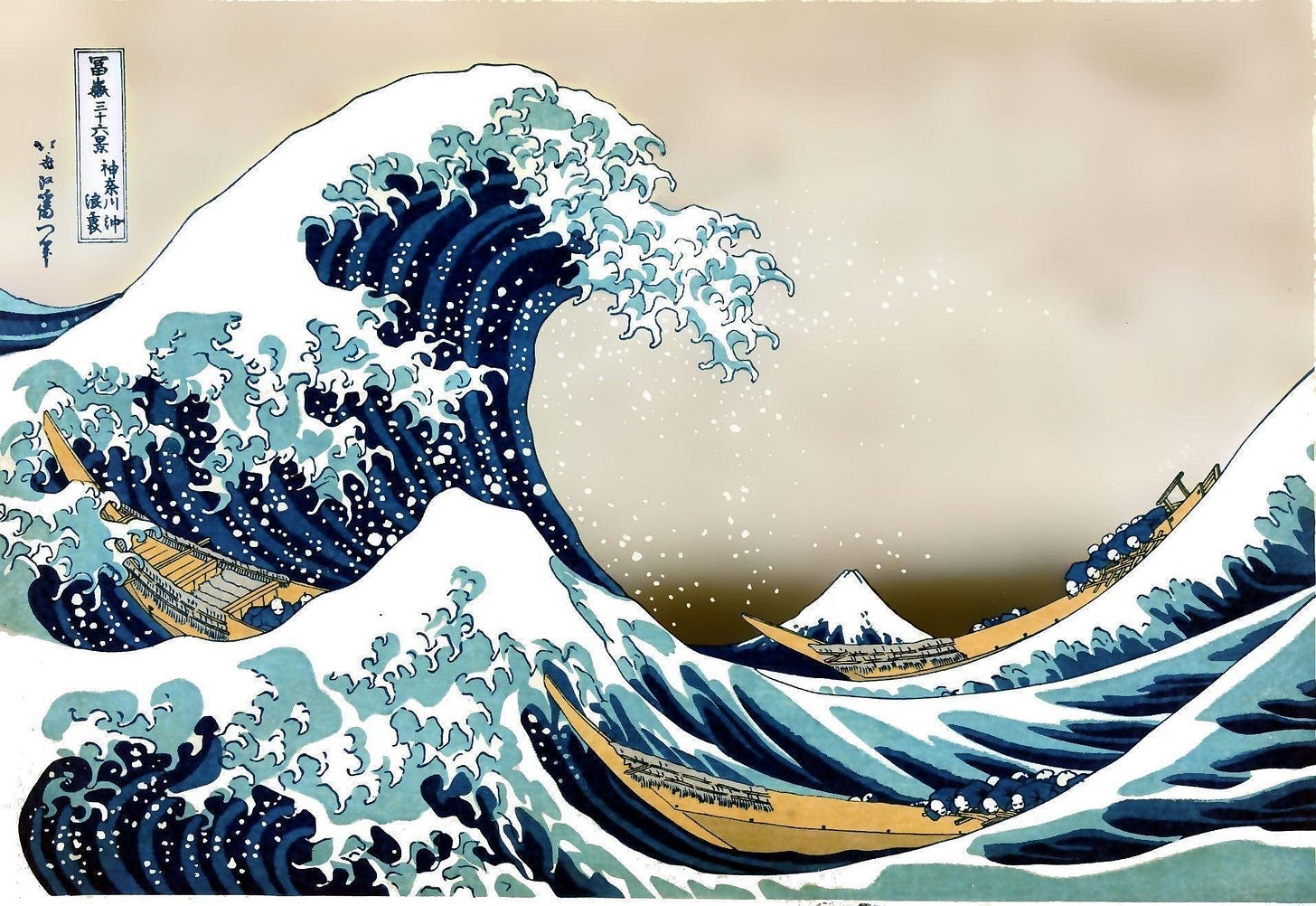

Panic in the West about the rise and seemingly inexorable conquest of global markets by Japan, Inc. seem to have crested like a great wave in 1990 or so. It all gave way to cognizance of a bubble economy and then to the spectacle of the bursting of that same bubble. Japan disappeared from the headline news in the West. Right now, we puzzle over whether or the economies of the West … and China and Japan and Korea and everywhere, are floating in massive debt bubbles. China itself seems to have been experiencing its own inexorable rise, but will unfavorable demographic trends and unsustainable debt put an end to all of that? Perhaps both American and Chinese imperia will experience retreat. And maybe that might not altogether be a bad thing. What would Mahan think?

"floating in massive debt bubbles" - I've wondered for a long time what that might mean. The nonsense done to hide the huge losses on 2008 by poor financial engineering have yet to managed. The US responded by creating money and others responded by doing much the same. The Chinese decided to build empty buildings to help a larger middle emerge. All of this debt is owned by someone aside from governments. It's the relative relationship between national currencies that seem to matter to facilitate trade. But it does seem to have peaked. The value of capital is starting to return but the real costs in terms of labor to produce that capital are starting to rise. Does that mean the easy wealth declines?

Joe's glass of beer will require a bit more effort but at least for the moment he can get the glass and there will be some beer. What happens when debt service erodes the outlay budget? Some of the vaulted Scandinavian economies are seeing great stress to continue down that path. And China still must calm a huge middle class grown used to comfort.

I think the great reset is arriving but not quite what some imagined. A lot of complacency has allowed incompetence to arrive nearly everywhere. Still the human spirit will continue to strive. The next generations may learn from errors and the repeating failures might be overcome with the help of technology. The revolution in agriculture and medical science will advance (despite the botched science recently).