Where are the adults?

The Russians have put a new offer on the table. Will the Americans allow the Ukrainians to respond with a counter-offer?

The Professionals –

It’s a late Saturday morning, early spring, 1990. I am browsing the shelves of Kramer’s Books just up the street from Dupont Circle in Washington, DC. I’ve gotten into this mode of buying books by people not like me about people not like me. I pick up The Remains of the Day (1989). A Japanese fellow (Kazuo Ishiguro) writes about the experience of a butler who orchestrates the grand goings-on at a grand, English country estate. It’s the 1930’s. The lord of the estate will be putting on a “peace conference” for European dignitaries. Hitler and the Nazis have assumed power in Germany. Should other European powers do something? Maybe nothing?

A consensus seems to be developing: Other Europeans should welcome or, at least, acquiesce to Hitler’s rise. The Nazis comprised a fringe political party in the 1920’s, but global depression discredited the governing elites and thereby elevated the Nazis. They swept in to power in 1932 and managed to impose order where everyone had expected chaos. That was certainly a narrative that the Nazis had hoped to project, and it was a narrative that Ishiguro’s fictional conferees had bought into.

Sweeping governing elites out of power was one thing. The real casualty of global depression was decentralization. Look how poorly “Capitalism” had performed. Look at the mess it had thrust the world into. It was long past time for the central authorities to assume a much bigger role in ordering economic affairs. Many observers looked to Hitler’s Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, and Stalin’s Russia—especially Stalin’s Russia—for new and better ways of doing things.

That may have been the real narrative that Ishiguro’s fictional conferees had already been disposed to buy into. Centralization was the in-thing, not just in Italy, Germany and Russia, but everywhere. Decentralization was out.

This was not lost on the best-and-brightest who populated the administration of Franklin Roosevelt. Indeed, the electorate had demanded that the government “Do Something!” in the face of global depression. Roosevelt campaigned on the promise to meet those demands, and, indeed, Roosevelt and his Democratic Party swept to power in the elections of November 1932. His administration and Congress wasted no time in rolling out their version of Build Back Better. They passed the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) in 1933, a body of legislation that laid the foundations for a centralized Leviathan. The Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional in 1934.

Back in the English countryside, an American attends Ishiguro’s fictional peace conference, the fictional Mr. Lewis, Senator from Pennsylvania. Lewis demonstrates himself to be the only contrarian at the conference, and he bluntly goes on to exclaim that the conferees are really just a bunch of dreamy “amateurs” who have allowed themselves to get caught up in a kind of emotive group-think. The business of hard-nosed, realist diplomacy should be left to the “professionals.” His harsh words are not appreciated.

The Humanitarians –

I think of Ishiguro’s hard-nosed Mr. Lewis quite often and wonder, where are these professionals? Where are these best-and-brightest professionals to step in, cut deals, and promote stability in foreign affairs? Where are the adults?

Maybe these professionals are a rare breed. Maybe we find ourselves mostly dealing not with professionals but with more of the of the self-anointed best-and-brightest who perceive that they’re the professionals. Can one point to any successes that these people have engineered?

In Groupthink (1982, 2nd edition), Irving Janis holds up the Kennedy administration’s management of the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) as an example of a successful effort to avoid groupthink and to secure a peaceful resolution to an affair that could easily have spun out of control. Granted, had the administration managed affairs involving Cuba more professionally to begin with, there might have been no crisis to deal with in the first place. Indeed, the professionals who navigated through the hazards in 1962 were much the same people who engineered the fiasco that was the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961. But, Janis argues that these people recognized that the Bay of Pigs fiasco revealed to themselves their own capacity for groupthink. They were not going to let it happen again. They went in to the hazardous business of inducing the Russians to pull their nuclear-tipped, ballistic missiles out of Cuba with a much more professional orientation.

Now, how many of these veterans of the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis then moved into the administration of Lyndon Johnson and then proceeded to engineer the nation-building project that was South Vietnam? Did these same self-anointed best-and-brightest who populate David Halberstam’s The Best and the Brightest (1969) manage to fall back into a facile, emotive groupthink? Irving Janis averred:

[T]he policy-makers in the Johnson administration were sincere democrats who prided themselves on their humanitarian outlook. How could they justify their decision to authorize search-and-destroy missions, fire-free zones, and the use of “whatever violent means are necessary to destroy the enemy’s sanctuaries”—all of which set the stage, the normative background, for the Mylai massacre and other acts of violence by the United State military forces against Vietnamese villagers?

Is ”humanitarian outlook” code for neo-Puritan will to build a “shining city on a hill” … on other people’s hills?

On the same page, Janis continued:

After leaving the government, Bill Moyers, an articulate member of Johnson’s in-group admitted: “With but rare exceptions we always seemed to be calculating the short-term consequences of each alternative at every step of the [policy-making] process, but no the long-term consequences. And with each succeeding short-range consequence we became more deeply a prisoner of the process.”

Have the people who bombed the Nordstream pipelines contemplated the long-term consequences of bombing the Nordstream pipelines? Russia had held out the prospect of renewing gas deliveries to Germany in return for Germany giving up on economic sanctions relating to the business in Ukraine. The bombing achieves the short-term consequence of frustrating the efforts of the Germans and the Russians to secure something approaching détente. That makes it less likely for the Ukrainians to secure détente with the Russians… at which point I keep finding myself coming back to the same top line conclusion with respect to the business in Ukraine: The United States could impose a peaceful resolution to the war by instructing the Ukrainians to cut a deal with the Russians. Ukraine would have to give up the oblasti of Donetsk and Luhansk, and now it looks like it might even have to give up the land-bridge linking those oblasti to the Crimea. That would entail giving up with city of Kherson which is situated at the mouth of the Dnipro River. Ukraine might be lucky to get away with holding on to the port of Odessa on the Black Sea.

The humanitarians both inside and outside the Biden administration might object—and some do object—that cutting any deal with “Putin” would amount to reprising the folly of cutting deals with Hitler in Munich in 1938. Hitler himself observed that “the Czech affair” of 1938 demonstrated that the Western powers were not going to do anything to stop him. The Nazis proceeded to absorb the whole of Czechoslovakia, not just the Sudetenland.

In this analogy, the oblasti of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia comprise the Sudetenland, and allowing Russia to absorb these territories merely sets up the Russians to absorb the rest of Ukraine. Now, it looks like the Ukrainians and the Russians were close to cutting a deal back in March or so, a deal by which Russia would only have absconded with Donetsk and Luhansk, territories that they had already been holding on to since 2014. But, it looks like the Western powers (the NATO/United States bloc) blew that up. And here we are.

The Narrators –

When diplomacy works, no one notices, but when things mess up, that creates opportunities for the same people who messed things up to heroically sweep in and make a show of cleaning up the mess. There is no glory in being competent. There can be great glory in governance-by-crisis.

I pose the fall of the regime of Ferdinand Marcos from the Philippines in 1986 as an example of diplomacy that worked. Remember that?

“People Power” swept Corazon Aquino to power in the wake of the Philippine elections of 1986. I say “the wake,” because both Aquino and Marcos had claimed to have won the elections. The Associated Press reported that “both Marcos and Mrs. Aquino, 53, were inaugurated as president of rival Philippine governments in separate ceremonies.” The Reagan administration then stepped in and suggested that it was time for “a peaceful transition”. Long story short: Marcos ultimately acquiesced. US Navy helicopters picked up Marcos and his family and swept them off to Clark Airforce base (in the Philippines). The Marcos family ultimately retreated to their luxury apartments in New York.

Civil war was averted, but not all of the self-anointed humanitarians could allow themselves to credit Ronald Reagan, and certainly not the Reagan administration, for enabling the result. For example, Stanley Karnow managed to regroup a few years after the Marcos affair to obliquely argue in The New York Times that Reagan had almost frustrated the effort to secure “a peaceful transition.” Karnow’s book, Vietnam: A History (1983), garnered a Pulitzer Prize, elevating the book above The Best and the Brightest (1969) to the status of the orthodox history of the Vietnam War. It was up to Karnow to articulate what the orthodox understanding of Reagan’s role in the Marcos affair should be:

Ronald Reagan … genuinely cherished the Marcoses. In 1969, Governor and Mrs. Reagan visited Manila, where Imelda’s opulent parties dazzled them. From then on, Reagan, impressed by Marcos’s exaggerated stories of his exploits as an anti-Japanese guerrilla, counted him among the world's “freedom fighters'” in the struggle against Communism. In Reagan's eyes, as one of his aides mused later, Marcos was “a hero on a bubble-gum card he had collected as a kid.”

Meanwhile:

[i]n Washington, a State Department task force fed Reagan massive evidence of Marcos's electoral abuses. But the President preferred his own sources. [Reagan’s wife] Nancy gave him information she was receiving by telephone from Imelda. Donald T. Regan, his chief of staff, and William Casey pressed him to stick with Marcos.

The professionals in the civil service (the State Department) were quietly getting things done, but it was those people in the Reagan Administration who were messing things up. Reagan had to be “force fed” the truth of things. That said, Karnow does seem to give Reagan’s Secretary of State, George Shultz, some credit for “interven[ing] vigorously” and securing the result. “Nancy, constantly on the telephone with [her BFF] Imelda, invited her and Ferdinand to America… Shultz ordered Bosworth to tell Marcos that his ‘time was up,’ and that ‘we will make the transition as peaceful as possible.’”

Stanley Karnow’s drive-by account of the Marcos affair may not be as penetrating as any of the vignettes in, say, Irving Janis’s Groupthink, but one can imagine that that affair does share much of the generic structure of any complex affair: There may be a lot of uncertainty about what is going on. People have to make judgments with limited information and limited time. Or they may have time to examine and then trial various options. They may have access to independent sources of information. They may ignore or discount certain sources. Or not. They may succumb to cognitive biases. Or not. Their decisions, whether wise or foolish, may or may not secure good results. Perceived success will make idiots look like geniuses. Perceived failure will make geniuses look like idiots.

Karnow’s account amounts, in my mind, to accountability-free, drive-by journalism. He does not prime the reader with an account of his basic proposition which might have been, “The Reagan Administration almost frustrated the peaceful transition of power in the Philippines in 1986.” The reader could then assess the argument, assess the evidence brought to bear, bring their own understanding of other evidence to bear, and ultimately decide whether or not the proposition holds up. Instead, we’re left with this suggestion that the Reagans were “dazzled” by autocrats like Marcos and his wife Imelda. The Reagans were disposed to personalize international affairs rather than leave it to the professionals to dispassionately intervene (or not intervene) in these matters. But, the narrator, having spoken no more than obliquely, can walk away from his own narrative, claiming, “I didn’t say that.” Like a drive-by assassin, he just speeds away and suffers no consequences.

Note that the Karnow portrait of Reagan shares much the same structure of the dominant media portrait of Trump: These people like dealing with autocrats. They personalize everything. They’re susceptible to being “dazzled” and (therefore) played. They’re friends with people like Marcos, Putin, Kim Jong Un, … Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, whomever the bad guy of the week is.

The Sleepwalkers –

Many of my earlier essays make contact with post-Meiji era Japan. Much of that material has been motivated by the idea that the United States, Japan and Britain could have avoided war in the Pacific (1941-1945), because they had so many parallel interests. Alfred T. Mahan seemed optimistic about relations between the three by the time he had published The Problem of Asia (1900). But, by the 1920’s, things were not working out. The parties do not seem to have been able to credibly commit to each other to leave the seaways open to each other.

I have more work to do before I can be confident in advancing some narratives that would explain why the parties failed to avoid war, but the parties do have the appearance of stepping closer and closer to war until, by 1940, everyone seemed to expect it. Absent some breakthrough, it was just a matter of when. Everyone knew this, especially after the United States imposed a crippling oil embargo on Japan in 1941. The Japanese would either have to come to the table to talk seriously about its interventions in China and Manchuria, or it would have to start a war on terms most advantageous to themselves. They chose the latter. But, why was the United States willing to risk war with Japan over matters in China? So many questions.

Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers (2012) has gotten some press in the wake of the business in Ukraine—as it should. The subtitle of the book is How Europe Went to War in 1914, but—no surprise—the book does not (and, perhaps, cannot) answer the question. The book is encyclopedic and reads better than one could expect an encyclopedia to read. But, if it reveals any elusive wisdom—that wisdom remains elusive, at least to me.

A traditional account of how the First World War unfolded might start with the “tinderbox” that was the Balkans. Indeed, much of the early part of The Sleepwalkers itself is occupied with “Serbian irredentism.” Through the course a Balkan War, another Balkan War and a host of other episodes, the Serbs were intent on assembling a Greater Serbia. But, one can’t help but think that a big motivation for that was opportunism. Empires were slowly disintegrating: Austro-Hungarian Empire to the north of the Balkans, Ottoman Empire to the south and east.

The Serbs, of course, were not the only ones who were active. The Bulgarians ran the Turks out of their neighborhood and nearly went so far as to take Istanbul. Meanwhile, Serbian irredentism irritated immediate neighbors. One party’s irredentism is another party’s illegal encroachment. There was a lot going on in the Balkans.

Outside observers took a keen interest in Balkan affairs. The Russians worried that Bulgarian success against the Turks might complicate Russian access from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, Germany shared a border with the Russian Empire, and the German leadership was concerned that an industrializing Russia might eventually turn its attention to Germany itself. Could the Germans find an excuse to fight a war with Russia before Russia would become too strong to resist?

One may recognize German concerns as an instance of the “Thucydides Trap”: a stronger power perceives the rise of a still yet weaker power as a threat; better to remedy the threat before the threat becomes a real thing. And then Britain may have perceived its own Thucydides Trap vis-à-vis Germany. Finally, we have the French who had been aching since 1870 to redress the humiliations of the settlement to the Franco-Prussian War.

So, how did Europe go to war in 1914? Perhaps the question should not concentrate on the particulars but rather on the general phenomenon about how it is that wars break out at all. By the time the summer of 1914 rolled around, many complex, interdependent processes were already at work. But most of these same processes were also at work in 1913 and 1912 and much earlier than that. These processes were all buzzing along their separate but interdependent trajectories. Was it not matter of merely flipping a coin about when war might engulf the great powers of Europe?

The Professional Coin Flippers –

If one believes implicitly that deterministic processes govern human affairs—kind of like Newtonian Mechanics—then it is easy to ask how it was that world war broke out in 1914. Or in 1939. Or in 1937 if one counts the Sino-Japanese War—the Second Sino-Japanese War—as the start of the Second World War. If one believes that deterministic processes govern human affairs, then it is easy to rationalize success and failure, tragedy and triumph, as the consequence of the right or wrong people doing the right or wrong things at the right or wrong time. One just has to go back and “connect the dots.” It’s just a matter of accounting. But, a lesson we might take from the metaphor of “The Butterfly Effect” is that, even if certain processes really are deterministic, we may never be able to know enough about those processes to forecast more than a very short time out about how those deterministic processes will evolve. Looking far enough out, those processes will yet appear entirely chaotic and beyond control. Do we really think the self-anointed professionals are equipped to intervene competently? Perhaps their role should be restricted to reducing the likelihood that a coin turns up the wrong way on a given day.

I have written earlier:

The Butterfly Effect is not what we popularly understand it to be. It’s not about how small perturbations in complex systems can induce spectacularly large effects but rather about how we might never be able to know enough about a given state of a complex system, even a deterministic system, to be able to avoid spectacularly large errors in our predictions of future states of the system…

The real butterfly effect comes to us from Edward Lorenz, “The Predictability of Flow which Possesses Many Scales of Motion,” Tellus 21 (1969), pp. 298-307. Lorenz actually characterizes it as more of a “Seagull effect,” …, we may not have the luxury of knowing everything about the state of a complex system at any given time, and it may be case that we can never acquire information that is fine enough to enable ourselves to fully ascertain a given state. We may yet miss arbitrarily small aspects of the system’s trajectory – the flapping of a sea gull’s wings, say –that could yet inform our prediction of that same trajectory. There may be a finite limit to what we can know about a system. And that can matter. Or not.

What should we expect of the professionals? Perhaps we should we expect them to surrender any conceit that they can mechanically program complex processes and that, at best, they might be able to identify hazards and set up deliberative processes for dealing with hazards. In this way, the governance of human affairs has a more constitutional character (we commit up front to processes for sorting through difficult problems) and less of a technocratic character (we deterministically program outcomes that may or may not prove to be implementable or desirable).

Now, does anyone really trust this man and his handlers to mechanically and deterministically deliver good results in Europe?

In 2012, the Obama campaign famously mocked the Romney campaign for its retrograde policy of vilifying Putin and the Russians. “The 1980’s are now calling to ask for their foreign policy back.” But, since 2016, the dominant clique in Washington has since gone on to vilify Putin and the Russians. Hillary Clinton and her retainers like John Podesta used the excuse of “Putin” to deny the integrity of the 2016 elections. That was bad enough, but, surprisingly, the dominant clique seems to have further cultivated the Putin narrative and impressed it into the service of driving the war in Ukraine.

The Ukraine business is hard to understand—unless one adopts a Manichaean view of things, a view of the basest, laziest thinking dressed up as “Dualism,” as a fight between the forces of Good and the forces of Evil.

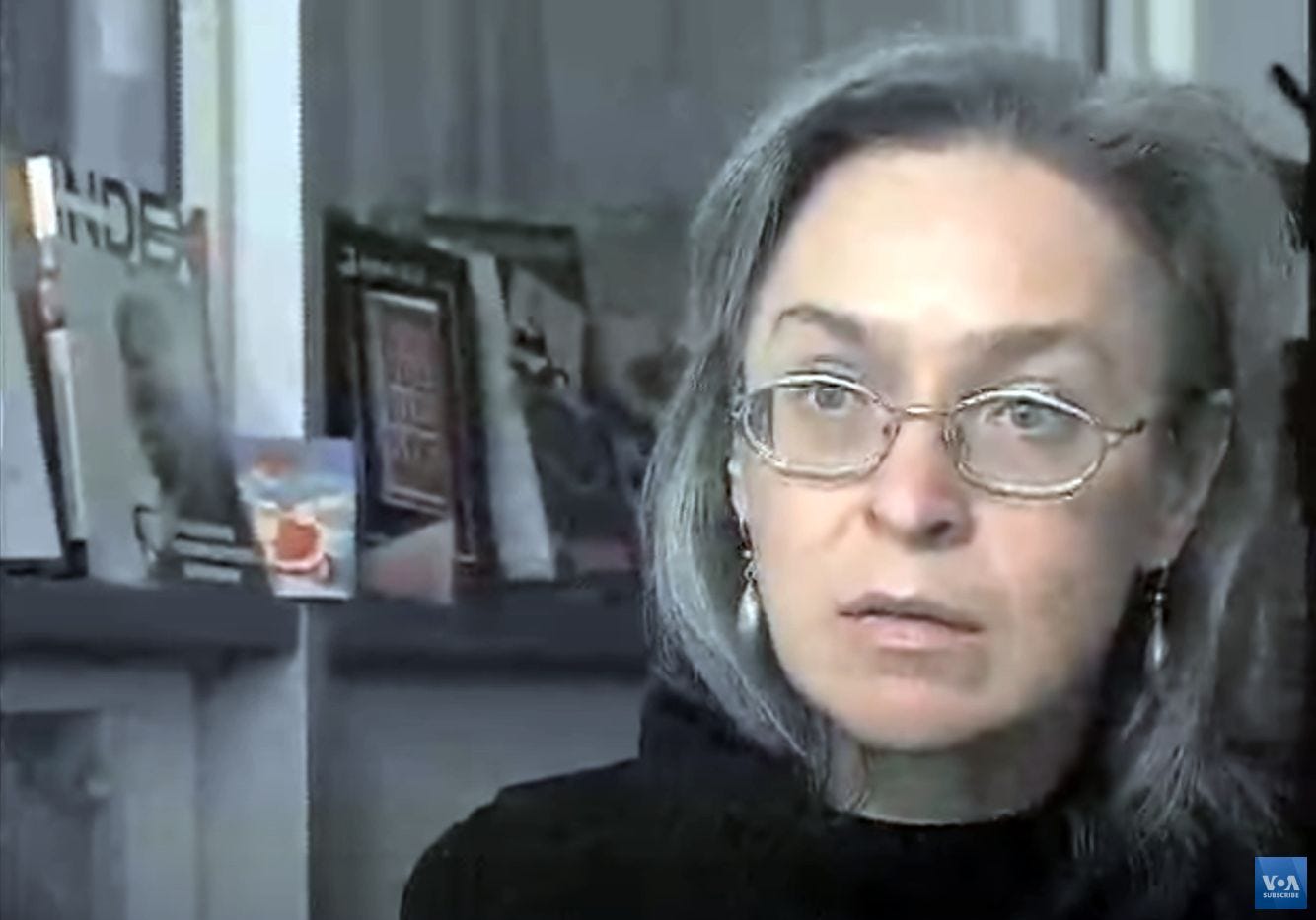

The first image that comes to mind when I think of Vladimir Putin’s role in the world is an image of … Vladimir Putin. He’s peering like a mischievous cat—a cat that knows something worth knowing—into the camera. The second image that comes to my mind is of Anna Politkovskaya, a journalist who was assassinated in her own apartment building in 2006.

I do not know much about Ms. Politkovskaya, but she appears to have been effective at revealing the machinations of the Putin regime, and it is hard not to think that the people who populate the Putin cabal thought much the same. She was too effective and had to be silenced.

So, yes. We’ve known since well before 2006 that the Putin cabal runs Russia more like a Mafia family enterprise than a democratic republic. But, I keep finding myself, again, coming back to the same top line conclusion on the Ukraine business. The Ukraine business may constitute but one episode in a relationship that the United States has affirmatively not endeavored to manage to the benefit of all parties. But, even after the war in Ukraine wraps up, there is still going to be a Russia. There may or may not be a Putin cabal in Russia, but there will be a ruling clique. That clique will not be occupied by good, liberal democrats.

We’re going to have a relationship with these people, whoever they are. But, are the humanitarians who are dictating policy in Washington factoring this fact in to their calculus?

The leadership in Washington, such as it is, has long demonstrated that it is not interested in peace with Russia or in peace in Europe. The Brits, the Poles, the Germans, the Ukrainians—they are being made to bear high costs for whatever delusional game the best-and-brightest in Washington think they’re playing. That game is not N-dimensional chess.

Washington could induce the parties fighting in Ukraine to cut a deal. I’d be willing to bet that the deal that the Ukrainians very nearly secured in March or April was better that the one they could right now secure. The Russians have reopened the bargaining process and have declared an opening bid: Recognize the four oblasti as Russian, commit to not joining NATO, and we will commit to leaving what’s left of you alone. Will the Ukrainians come back with a counter-offer?

But, there is then the question of how the parties ended up fighting in the first place, especially since Putin and the Russians have been warning us for nearly two decades that folding Ukraine into the NATO sphere would be something that they would interpret as very hazardous. They would be willing to fight.

This last bit has much the flavor of the United States decision to invade North Korea in the fall of 1950. Recall that the North Koreans had invaded the south in June of that year; South Korean and American forces finally managed to hold up the North Koreans outside of the port city of Pusan. The Inchon landing of September changed everything, catching the North by surprise and enabling the Americans to reconsolidate the South. The decision was then made to overrun the North and reunify the whole of Korea.

Douglas MacArthur sent his troops racing to the Yalu River, the border between China and North Korea. The Chinese had already warned the United States against invading the North, and they had even sent some units into the North to support the North Koreans. American units then reported affirmative contact with Chinese units. These Chinese units subsequently withdrew, but the Chinese continued to warn the United States that Chinese armies would cross the Yalu River were the United States to persist. But, the American leadership blew off the warnings and the evidence that the Chinese were serious. MacArthur’s troops kept racing to the north.

The American units were dispersed, disorganized and vulnerable by the time the Chinese did invade. The Chinese invasion set up fraught scenes such as the encirclement of a few American divisions by many times more Chinese divisions at the Chosen Reservoir. The American units did manage to fight their way out and withdraw, notwithstanding Chinese intentions to annihilate all American units. “The Frozen Chosen” managed to avoid the fate of the British who had to withdraw from Kabul in the winter of 1842, but they did suffer grievous losses.

Does that not sound familiar? American units pressed ahead and made themselves vulnerable despite credible concerns that they might be setting themselves up for a trap of their own making.

That said, it is easy, is it not, to indulge in ex post rationalizing and to see the wisdom of things only once the data have come in. But it is hard not to see parallels with the matter in Ukraine. The Russians had been sending warnings for a long time and had even gone so far as to actually invade Ukraine some years earlier. The matter of that earlier invasion had yet to be resolved. But, still the Ukrainians and their American sponsors found themselves flat-footed when the Russians finally did invade this last February.

It is hard to imagine the United States acquiescing to a deal in Ukraine before the midterm elections. Maybe it amounts to more hope than realism to expect a deal soon after the elections, but the Russians’ latest offer is on the table. What will the United States allow the Ukrainians to respond with?

We can only hope no one in the Russian chain of command is as stupid or crazy as whichever Americans made the decision to destroy the Nordstream pipelines.

I would expect anyone (like me) who has studied the history of Russia to resolve to whatever extent possible never to go to war with that country. Russia is not like the United States, but that does not mean we shouldn't try as hard as we can to be friends.

The current American leadership absolutely disgusts me.

Nice refresh on history. While I've often read many histories that attempt to explain the why of war they always attempt to explain often irrational decisions made retrospectively. At the time they seemed wise and justified.

In terms of Ukraine, the Donbas has been historically a complex issue going all the way back to the Holodomor of the 1930's. The resettlement of Russians in the area afterwards has been a friction point to the ethnicities involved. Whether the E-W divides can be managed from Kiev has been an issue but one for the Ukrainians to sort. Russia's stealth annexation of Crimea led to a complete restructuring of the Ukraine military that now has become quite capable.

My take on what Putin has done relates to an apparent inability to quell unrest in the Donbas in Russia's favor. He was not winning militarily nor with hearts and minds. He mounted a huge threat right on the border of a low level combat zone and even that was not improving the Russian situation. His decision to try for a quick invasion failed because he badly misjudged Ukraine sentiment and a much stronger military. The truly inaptness of his attack assumed an awful lot, a failure of logistical planning. The nominal ability of his artillery to create victories has now been negated by better US supplied artillery. He has wasted a lot of expensive munitions on pointless targets and now has run out of the smarter weapons. While the Russians have always been less concerned over soldier's lives, his current tactics have resulted in huge losses that now matter.

Where this goes as Ukraine steadily rolls Russian troops back is unknown. Putin is in a very bad place and perhaps finds losing intolerable. I don't think Ukraine will settle until it retakes Crimea. Russian equipment is beginning to become impossible to replace or repair. Sanctions have worked well in terms of limiting Russian arms production. Sanction are now being felt in the overall economy as well but Russians are used to deprivation. Whether we can return to the days pre-2014 with Sevastopol and Crimea holding a long term Russian facility lease is uncertain, but Russia can't accept not having that port. A veritable rock and hard place issue as the war drags on. We could end it by denying supports but face a political backlash for that both domestically and internationally.