Who Runs Administrative Agencies?

“Personnel is policy,” but it is not an autonomous Deep State that makes policy. It’s a cadre of political appointees at the top of administrative agencies who impose it.

There is an old question in political science: Who runs administrative agencies? Let me pose four hypotheses and then suggest that one of them really does go some way toward framing a reasonable answer.

The Legislature: In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, a body of literature in political science explored the idea of “Congressional Dominance”: The United States Congress, through its “power of the purse,” exerts much indirect control of administrative agencies. The threat of withholding funding is potent.

The “Deep State”: Administrative agencies operate autonomously, largely insulated from judicial oversight and from political oversight. Business interests end up being impressed into operating as agents of the Deep State. A kind of Corporatism obtains.

The Executive: The President and the senior political appointees exert much control over administrative agencies; administrative agencies actually are subject to effective political oversight, although some agencies are largely insulated from judicial oversight.

The Oligarchy: This is a tale of “regulatory capture.” Administrative agencies effectively operate as agents of powerful business interests. Note, not all business interests. Just those of a compact oligarchy.

Spoiler alert: My answer to the question is that the Deep State hypothesis may be abundantly plausible, but the Executive really does exert the most important influence in running administrative agencies. In fact, going into the project, I expected to get some action out of the Deep State concept, partly because the language administrative agencies have been using these last twenty years is consistent with it. Their language has been all about “collaboration” between “stakeholders” in the crafting and implementation of policy, and it all had the appearance of administrative agencies cartelizing industry under the guise of that “collaboration.” All of this conforms to a kind of neo-Corporatism insofar as government ends up bullying private parties into following its diktats.

Also, I’ve had the privilege of talking to the senior bureaucrats who manage a particular program, and they are (were?) very ideologically committed to certain interpretations of their mission. I asked questions, and these people yelled at me. They didn’t like probing questions… But, the data tell a different story. There can be sharp differences in how administrative agencies operate from one administration to the next. Indeed, in my data, the administrations of Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump stand out in sharp contrast to all of the others. Oddly the administration of George W. Bush looks a lot more like the administrations of Carter, Clinton and Obama.

In any case … My results suggest that the Deep State does not operate autonomously but can be house-trained.

The screenshot above is from an episode, “A Victory for Democracy,” from the Yes, Prime Minister series. That episode actually dramatized the Deep State proposition: The entrenched civil service would make a point of “house-training” new political appointees. In contrast, my research about a particular program supports the idea that there is something to “personnel is policy,” but those personnel are the political appointees at the top of the administrative agencies, not the denizens of the Deep State.

In the last year, I finally took the time to assemble a first draft for a research project I’d been sitting on for a long time. I’d been sitting on it, because the data I collected (a big task) are interesting, but they don’t provide a high-resolution perspective on what is going on in administrative agencies—or, in the case of my project, of a specific administrative entity, the Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy program (EERE) over at the Department of Energy (DOE). I feel like Galileo looking out on the universe through his home-made telescope. It was not the James Webb telescope (the successor to the Hubble telescope) … but one could yet discern important features of the cosmos. Like the moons of Jupiter. Up to that point, who knew that Jupiter had moons?

So, I can discern some important structure, and a friend suggested that some of my results accord with an observation Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch had advanced in his concurring opinion in Loper Bright v. Raimondo (2024). (Go to page 48 of this bundle of all of the Justices’ opinions in Loper Bright. Raimondo was the Secretary of Commerce in the Biden Administration.) That matter, recall, involved the last, definitive whittling away of “Chevron deference.” As I’d written before, “Chevron deference derived from Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council (1984). That Supreme Court opinion basically afforded administration agencies a layer of insulation from the processes of judicial review contemplated by the Administrative Procedures Act of 1946. Loper removes that layer of insulation, …”

Chevron allowed courts to defer to the administrative agencies for interpretations of statutes and for understandings of how to apply statutes. So, if some party had managed to drag an administrative agency into court, the court could easily dispatch the case on what would really amount to a technicality: the agency knows what it’s doing; that’s where the experts are concentrated; we’re going to defer to the interpretations advanced by the technocrats and dismiss the case. That comprises the technocratic conceit in action.

Gorsuch could yet observe, however, an inconvenient feature of administrative process that would compromise the technocratic conceit: interpretations and applications could vary widely from one administration to the next. So, whose particular set of technocrats were doing the best job of interpreting and applying statutes? Are the experts actually revealing how shallow their expertise is if they demonstrate so much disagreement between themselves from one administration to the next? Does expertise not constitute some orthodox body of “Settled Science?” Evidently it does not.

I myself could document divergent interpretation and application of statutes pertaining to a particular body of administrative law: energy efficiency standards coming out of the EERE. The efficiency standards regime was launched in the wake of the 1973 “oil shock.” Government had to do something about the resulting “energy crisis,” real or imagined. Energy efficiency standards constituted but one part of those stultifying and suffocating “whole-of-government” campaigns against a manufactured and hyped crisis. But, the efficiency standards regime really got going with the administration of Jimmy Carter (1977-1980). It was the Carter administration that created the Department of Energy, and it was the Carter administration that first started making a serious effort to craft efficiency standards for major appliances (air conditioners, heaters, dishwashers).

The Reagan administration (1981-1988) appealed to Congress to extirpate the energy efficiency regime, but Congress declined. The administration then set about working within the EERE framework to roll it back. But, that met with a serious challenge from the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) out of which emerged the opinion in Natural Resources Defense Council v. Herrington (1986). (Herrington was the Secretary of the Department of Energy.) Herrington required the DOE to stop affirmatively rolling back EERE standards. So, the administration could not rollback standards that had already been run through the rulemaking process, but the administration stopped advancing new standards or ratcheting up existing standards. It could neither rollback nor extirpate the EERE program, but it could render it moribund for the course of its tenure.

The administration of George H.W. Bush (1989-1992) might have been marginally more active in the EERE space, but the Clinton Administration (1993-2000) did take up the business of advancing standards more aggressively. But, not as aggressively, it turns out, as the administration of George W. Bush (2001-2008). Coming in to George Bush’s second term, the administration reorganized the entire program and started to aggressively expand the range of products subject to EERE standards. Never mind merely regulating air conditioners. The EERE regime would now encompass electric toothbrushes.

The administration of Barack Obama (2009-2016) merely took up where the Bush administration had left off, although the Obama administration started to ratchet up the volume of EERE “rulemaking” processes in the closing years of the administration.

That is when I became aware of the EERE program. It turns out that, since the early 1990’s, the EERE had been required to secure an opinion from the Antitrust Division (ATR) of the Department of Justice about the potential consequences of each new EERE rule for competition in markets. What this really meant was that ATR would get a fleeting chance to look very superficially into what was going in markets implicated by a given EERE standard and to then offer an opinion about possible consequences for competition.

Obama’s EERE program was churning out so many new rules that ATR was getting inundated with demands to do these laughably superficial reviews … and I got asked to help dispatch some number of these requests. This was late 2015.

This business of reviewing EERE standards constituted my first experience in really digging into administrative “rulemaking” processes. It all sounded so deadly boring: “Notices of Proposed Rules,” “Supplemental Notices of Proposed Rules,” “Advanced Notices of Proposed Rules,” requests for information, “Final Rules,” and the rare “Withdrawn Rules.” NOPRS, SNOPRS, ANOPRS, and FRS. And then there were these mysterious “Direct Final Rules,” DFRS. And these notices and rules could each run hundreds of pages. But, the key is to filter out the noise and identify what’s basically going on. No need to be intimidated by all of the bureaucratic blather.

My first experience in this business was illuminating. My colleague and I identified a potentially very serious problem with a proposed rule. That problem could induce a host of (mostly smaller) firms to exit a particular market. The cost of compliance with the new rule would have just been too much for them. Better to cede the market to large firms by virtue of the fact that these large firms had already developed much capacity in dealing with “regulatory affairs.” So, we presented our concerns, … and people I had never seen before showed up to weigh in. One might have thought that my colleague and I were holding up the Supertanker of State and that doing so amounted to precipitating a crisis.

The publicly available, very dangerous letter (edited by a committee of way too many chefs) that we ended up sending back to the DOE is posted here: https://www.regulations.gov/document/EERE-2011-BT-STD-0031-0053

It was after that experience that I decided to see if I could get information on the universe of EERE rulemaking processes going all the way back to the 1970’s. That made for a big task, but I managed to get a hold of more than 20,000 documents and to algorithmically extract interesting information from these documents.

I am not going to go into all of the results here except to highlight the one point: Both the volume and content of EERE activity could vary sharply from one administration to the next. Career staff in the EERE program might be ideologically committed to expanding EERE standards and to ratcheting them up as far as they can, but these same staff really do respond to adult supervision from above. The senior cadre of political appointees that come and go with each new administration really do exert heavy influence over the conduct of the erstwhile Deep Staters.

Making Appliances Great Again

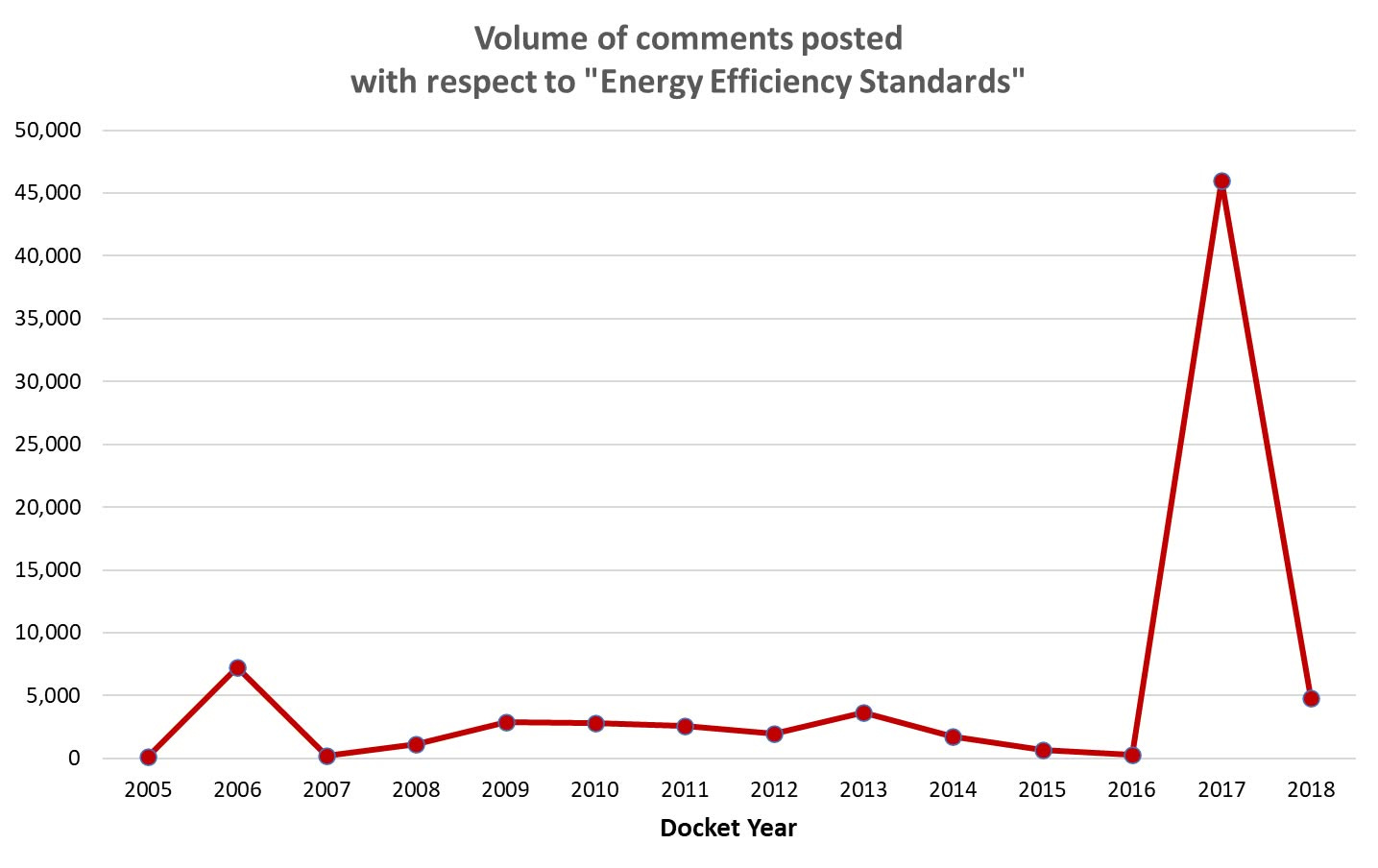

Here is an entertaining graph:

Like any rulemaking program, the EERE is required to solicit public comments on proposed rules. I map here the frequency of comments by year. Generally, comments numbered fewer than 5,000 in a given year, but in 2017 they exceeded 45,000. What was going on?

The new Trump administration had proposed rolling back certain standards that had been proposed late in the Obama administration. Such new proposals elicited an enormous volume of comments in the spirit of “Make Appliances Great Again!” That was definitely a vivid indication that leadership from senior political appointees could be potent.

Now, what about those other hypotheses about “Who controls administrative agencies?” The “Congressional Dominance” concept comes to us from a much more innocent time. There was a time when the Executive routinely satisfied its Constitutionally-mandated responsibility to propose an annual federal budget. Proposing a budget involved proposing budget priorities to Congress, and then Congress would do its horse-trading and eventually come up with a budget that could secure passage through both the House of Representatives and the Senate. And then the President would sign it, albeit possibly after threatening to not sign it as a way of securing a few tweaks.

With a budget in place, Congress would be situated to make “appropriations”—that is, to actually approve funds for government programs. The threat of reducing budgets or withholding appropriations could enable Congress to influence the conduct of the administrative agencies.

So, this idea is interesting in that administrative agencies may constitute the operational part of the executive branch of government, but “Congressional Dominance” suggests that the real executive authority is vested in Congress, not the Executive. The President doesn’t run anything. Congress does.

Maybe there was something to this 50 years ago. Maybe, but, not for the last 30 years at least.

What of “regulatory capture” and the dominance of the Oligarchy? There is some very nice research by Terry Moe from early 1980’s that, on my reading, can be summarized as “Administrative agencies were designed to be captured!” That is, the agencies really do factor in the interests of “stakeholders” and constitute part of the foundation of “Stakeholder Capitalism.” I think there is something to this, but my own view has diverged somewhat. Going in to the project, I was thinking not so much that government agencies would work as agents of an Oligarchy but that administrative agencies might actually bully business interests into operating as agents of those same administrative agencies and thereby expressing the policy preferences of those administrative agencies. More emphasis on “sustainability” and “decarbonization?” Of course, private enterprise would oblige. More “DEI”? Whatever you say. “ESG” and “LGBTQ+?” Sure.

So, no, I don’t really see regulatory capture at work, and I would recast the appearance of Stakeholder Capitalism as something more in the spirit of neo-Corporatism: Administrative agencies really do bully the private sector, and they are very effective at doing it, but it is not the Deep State that is doing the bullying, per se. It is the cadre of senior political appointees who are using the machinery of administrative rulemaking processes to bully the private sector. Leadership from the Executive is most determinative, and that leadership can result in outcomes that are consistent with Stakeholder Capitalism. It depends on who’s leading the agencies.

* * *

As I tap out this essay, leading Democrats are right now complaining that the new Trump Administration is thrusting the country into a “Constitutional Crisis” by virtue of exercising executive control of administrative agencies. Let’s say that again: The Executive is exercising control over the Executive, and the people who don’t like the policy preferences being implemented are calling this control “unconstitutional.” They want the Great Grift running at a few $trillion per year through the administrative agencies to keep going. They don’t like the fact that Elon Musk and DOGE are exposing the staggering volume of “waste, fraud and abuse.”

They are effectively claiming that the only Constitutionally-credible way to run the country is to allow the Deep State to autonomously run the administrative agencies. It would thus be up to administrative agencies to take on the legislative function of making “administrative law” and to commandeer the executive function of enforcement in enforcing that same law. On top of that, administrative law should be insulated from judicial review; outside parties should not be granted the right of being able to force the administrative agencies justify the constitutionality of their own rules in front of a third party (the court).

This Deep State vision of government does complete violence to the “separation of powers” by bundling the executive and legislative functions within the administrative agencies themselves and by freezing out the prospect of judicial review. And, as I have noted many times before, this totalitarian vision of agency autonomy has been crisply articulated by such celebrated Deep State proponents as James Landis in his Deep State operating manual, The Administrative Process (1938).

An outstanding research project for me is to look into the background of the Administrative Procedures Act of 1946 (APA), for I am guessing that the Act was inspired by abuses that veterans of the administration of Franklin Roosevelt (which would include James Landis) had inflicted on the country through the course of the Great Depression and the Second World War.

Ostensibly, the APA rendered the administrative agencies more amenable to judicial review. Yet, nearly 40 years later, Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council (1984) largely put an end to private parties challenging administrative agencies, a result that pleased the NRDC, notwithstanding the fact that the NRDC had made recourse to judicial review in Natural Resources Defense Council v. Herrington (1986). In both matters, the NRDC favored more rules and regulation as a way of compelling private parties to conform to its preferred policies.

Right now, the Democrats are looking for federal circuit court judges who would be amenable to frustrating the efforts of the Executive to cut spending at administrative agencies. The idea seems to be that, like Obama, the Executive can deploy “a phone and a pen” to launch new spending and create new administrative entities, but the Executive should not be able to rollback spending at those same entities or to fold up the operations of those entities. The Democrats are the ones who might be setting up a “Constitutional Crisis,” and it might be a good thing to have their crusade crushed in the courts.