Who’s Afraid of Tariffs?

Tariffs and non-tariff barriers are bad for everyone unless you’re a poor fellow in South Korea in 1961.

Quick note.

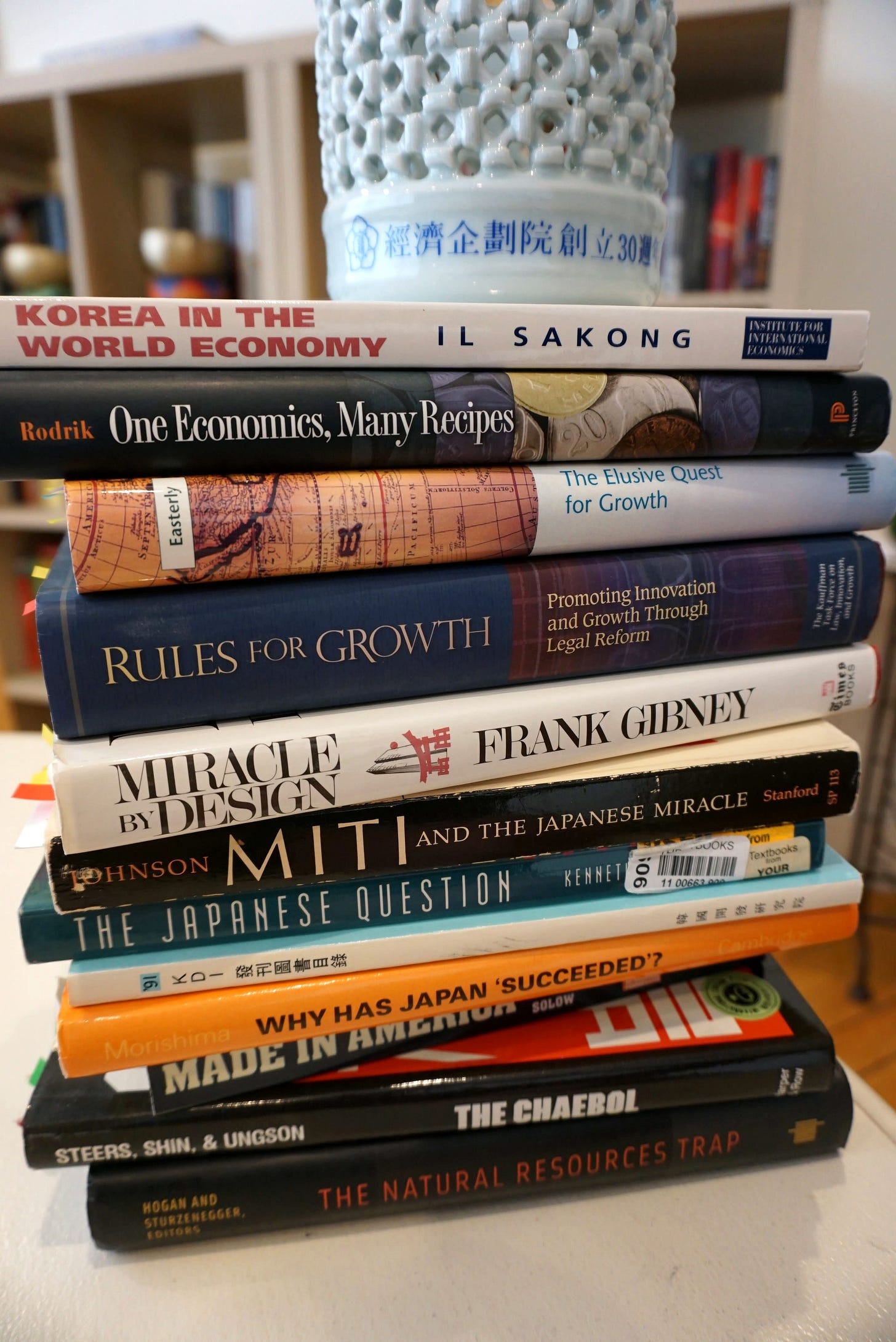

I have to thank whomever sent me a hardcover copy of Rules for Growth: Promoting Innovation and Growth through Legal Reform (2011). This was some years ago.

The authors of the first chapter of the book pose an important question: “Why do economies grow?”

This question, which once occupied the attention of the first "economists"—among them, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and others—has continued to bedevil economists over the past several decades. By and large, economists have been better able to describe how growth happens rather than to predict it or to prove that particular policies are responsible for it.

One might have expected that economists would have figured this out. Is there not an optimal program that would, say, place a poor society on a Sendero Luminoso—a tried, true and well-traveled “Shining Path”—from poverty to prosperity?

Many times I’ve noted that Lenin thought that he had stumbled upon the optimal program: Just do what “the capitalists” would do, but make one tweak to the program: share all of the fabulous wealth and abundance equally rather than allow the “the exploiters” to keep it to themselves.

The optimal program, Lenin averred, had been laid out in Frederick W. Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management (1919). In his futuristic novel We (1923), Yevgeny Zamyatin was quick to make fun of the Bolshevik regime’s enthusiasm for “the Taylor system.” Not long after that, Ludwig von Mises himself piped in, dismissing Lenin’s prescription for economic growth and prosperity as a product of a “bureaucratic mind” that reduces everything to unambiguously mechanistic, implementable programs.

The Leninist program didn’t really work out as well as the Soviet leadership expected, but readers will know that the Trump Administration is in the process of rolling out its own mechanistic growth program: match other countries’ tariff and non-tariff trade barriers with tariffs. If foreign exporters want to access American markets, they can either pay tariffs or (the Administration hopes) avoid tariffs by setting up production in the United States.

Most economists appear to dismiss the Administration’s tariff gambit as just that: a silly gambit that is motivated by very shallow thinking. Tariffs really amount to taxes, and these taxes artificially raise the costs of producing everything. Never mind who ostensibly pays the tax. These taxes merely make it harder for producers to efficiently organize production. A given producer’s efficient option might have been to source certain inputs from abroad, but now those inputs will be more costly or that producer will source inputs from domestic suppliers who, absent tariffs, wouldn’t have been as cost-effective as foreign suppliers. It’s hard not to expect that, after all parties have adapted their logistical networks to the new tariff regime, the entire economic system ends up operating at higher cost to produce everything. We experience an important episode of inflation.

And, it can be worse than that, for tariffs may create political constituencies (coalitions of inefficient producers) that agitate for maintaining these tariffs. Tariffs may be easy to implement but harder to remove, in which case we end up inducing the economic system and the political system to fall into a less productive, sclerotic equilibrium.

The most orthodox opinion would seem to be: tariffs are bad for everyone. All countries should get rid of tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade. Let labor and investment go wherever it wants to go. Don’t impose artificial barriers. Rather, let the magic of the market lead us to the optimal allocation of resources, and then we can get all our stuff at least cost. What’s not to like?

I would suggest that “What’s not to like?” is not a flippant question, for it would force the proponents of tariffs to make a more serious case. But, let’s note that the case for globally relieving all tariffs corresponds to a libertarian vision of global governance. In this vision of how the entire world should work, one unit of capital is a perfect substitute for another unit of capital; one unit of labor is perfect substitute for any other. Just follow the Leninist program: give everyone proper training and surely one could find an Indonesian oyster shucker who could substitute for a Ukrainian oyster shucker who could work alongside a Russian oyster shucker. The whole point is that production and distribution really just comprise a mathematical construct, and that construct is amenable to unambiguous optimization. Tariffs and non-tariff barriers frustrate optimization.

Then there is the matter of the illegal immigration of particle physicists coming across the English Channel in rubber boats from Calais to Dover. These people may be coming from villages tucked away in the valleys of the Hindu Kush (Pakistan) or from villages dispersed across the Maghreb (North Africa), but their talents could be deployed with financial firms operating in “the City of London,” for it is at just such places that skills in modeling Brownian motions would be valued. Their immigration should be rendered entirely legal, and we should dispense with the rubber boats and allow labor to move across all borders freely.

I suppose there should be some question of why the particle physicists from Pakistan and the Maghreb could not efficiently deploy their services in modeling stochastic processes while remaining back in Pakistan or the Maghreb. That question brings to mind a question that Professor Brad Pitt had posed years ago when he was still absorbed in his “Brangelina” phase of economic policy consulting. I think he was off somewhere in Thailand where he had observed that some villagers tucked away in the jungles (of Burma? Of Thailand?) had this practice of selling off their young daughters to entrepreneurs operating in big cities like Bangkok. I can’t find a specific citation, but I can recall him asking something in the spirit of “Why can’t it be in Burma what it is like in a model of ‘Pleasantville’ like Bloomington, Indiana [home of the University of Indiana]?” Good question! Why can’t we just take some random village in Burma, say, and run it like Bloomington? Surely the Burmese authorities, who at one time were celebrated darlings of the International Community, would be pleased to make way for such projects.

In The Elusive Quest for Growth (2003) William Easterly recounts his transition from a young man optimistic in policy prescriptions for unleashing growth in underdeveloped countries to a somewhat frustrated but wiser older man with experience in seeing development programs fail. Turning a random Burmese village into Bloomington was not so easy. Indeed, turning East Palestine, Ohio into Bloomington might not be so easy, either. What’s missing?

I don’t know, but the contributors to Rules for Growth (2011) argue that some answers would have something to do with “good institutions.” You know, stuff like “the rule of law,” but, not, I would suggest this counterfeit version of the rule of law that the kind of people who cancel elections in Europe pass off as “the rules-based order.” Meanwhile, there are experiences like that of post-war Japan or South Korea post-1961 that seem to offer some ideas about how to inspire vigorous economic growth, and some of those ideas would involve … tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade. Hmm …

Let me focus on the Korean experience, since I have had the privilege of querying Korean government officials about economic policy during the year-and-a-half I had found myself ensconced in one of their offices. This was during my stint at what was then South Korea’s Economic Planning Board (EPB).

It was just before going to Korea that I made my first contact with the United States Agency for International Development, the infamous USAID. The account I read suggested that, after the Korean War (1950-1953), the Korean economy stagnated. Activity largely involved a small number of well-connected families gaming aid channeled through USAID. Enter Park Chung Hee. He led a military coup in 1960, and his people quickly set up a new economic development program. They established the EPB in 1961 and charged that agency with coordinating development plans across all economic ministries.

As far as I could tell, the Korean government took over the financial sector of the economy (such as it was), and used the role of gatekeeper as a way of influencing how entities in the private sector would invest. Specifically, the government gave up any pretense of honoring free market principles and got explicitly into the business of “picking winners!” The government identified industrial sectors into which it encouraged firms to invest, and it would channel what limited financial resources it controlled into those sectors. And, so, it was by the government’s direction that a principally agriculture-based economy started to channel resources into things like ship-building and petro-chemicals. And, the country as a whole had success in building ships and building refineries. Korean firms started to capture global market share.

Government as Private Equity Firm

Now, was the government-directed investment program the optimal program? Did the program guidance come out of some finely-tuned economic modeling and econometric validation? Surely not. Government officials set about doing what private equity firms do: look for opportunities and do their best to put some crude numbers on their investment proposals. And then they’d fight over which projects and which firms and which sectors would get preferential access to funding, and that would be that.

According to a former Minister of Finance, Il Sa Kong, the country’s economic program also involved gatekeeping access to the Korean market. (Dr. Il himself had a hand in approving the entry of certain foreign banks into the Korean banking sector. He sketched his concept of the basic Korean program in Korea in the World Economy 1993, published by an outfit managed by William Easterly.) The gatekeeping could involve tariffs, but it also involved a host of non-tariff barriers or, at least, important conditions on foreign investment. So, for example, were a foreign firm interested in establishing a presence in the Korean market, the government would require it to find a Korean partner with which to form a joint venture. Kentucky Fried Chicken ended up partnering with the Oriental Brewing Company, which was why one could get a beer at any KFC in Seoul.

Joint ventures often involved (required) important technology transfers. But, there were takers. South Korea may have been a small country, but plenty of big, multinational firms were interested in tapping into that market of 45 million consumers. (Imagine the attraction of investing in order to get access to a market of 340 million consumers! That’s part of the Trump Administration’s pitch.)

My sense is that, as the economy became more sophisticated, demands increased for the government to loosen its grip on the financial sector. (Hence the entry of foreign banks and such, although the regulators were wary of “hot money” of the Soros type moving in and out of the Korean won and introducing much flux into foreign exchange rates.) That said, the government officials around me were charged with thinking deep thoughts about how to induce the sophistication of the economy. One of my “deputy directors” had been thinking about what it would take for Korean firms to start developing a regional aircraft. Here the idea was that developing domestic capacity in aero-space would inspire development of an entire ecosystem of high-tech parts suppliers. I don’t know that that particular project went anywhere, but it is true that Korean firms did move into automobile manufacturing and did develop an entire ecosystem of suppliers dedicated to supporting that industry.

Now, should the Koreans have bothered with automobile manufacturing, aero-space ventures, ship building and petro-chemicals? Shouldn’t they have simply concentrated on their “comparative advantage” in … what in 1961? Garment manufacturing? Shoe-making? Why not, say, leave it to Japanese, American and European firms to dominate automobile manufacturing?

The Korean development program was, of course, explicitly nationalistic. It set up its “national champions” to compete vigorously with foreign firms … in foreign markets. It was only over the decades that Korea only slowly opened up certain markets (mostly in services) to some modest degrees of foreign competition. And, yet Korea had managed to situate itself among the most economically developed countries in the world. Not bad for a small, agriculturally-based country that had been ravaged by war in the early 1950’s.

So, does the Korean experience illuminate the shining path to economic growth and prosperity? Not necessarily. Other countries have plenty of experience with “import substitution,” and while Korea may have had success with policies consistent with “import substitution,” it is not obvious that all other countries have. But, according to the no-tariffs advice, we shouldn’t care about import substitution. We should just let labor and capital move to wherever it wants, anyway. Right? This nationalism business just amounts to a costly fetish. Right?

I leave it to the open-borders fetishists to fight it out with the nationalism fetishists. Although, if forced to pick a side, my choice would be easy. In fact, I admit to having much impatience with the no-border fetishists, because “good institutions” are not cognizable through the lens of their neoclassical models of markets and production. As Harold Demsetz (a wonderfully grumpy institutionalist) might suggest, a problem with the off-the-shelf textbook neoclassical model is that it may (and does) serve important purposes, but it corresponds to what Vernon Smith would call the “institution-free core” of economic theory. Worse—and I can hear Grumpy Uncle Harold say this—it can’t even recognize what a firm is.

That’s right friends. In the “neoclassical theory of the firm,” there really is no firm. What there are, instead, are production functions and prices pinging around the hypothetical economy like electrical impulses in “the central nervous system of the economy.” That body of theory has nothing to say about how to promote economic growth. It can motivate a static concept of resource allocation in a closed economy populated by stick-figure firms, but that’s about it.

Maybe the Koreans were on to something, and so, too, the Japanese before them. We will see what comes of the Trump Administration’s own avowedly nationalist plan to promote economic growth within the United States. Firms—actual firms, not stick-figure abstractions—may do a lot of resorting. The Trump Administration surely hopes so, although I note the Trump tariff program can support the no-tariffs fetish: If other countries drop their tariffs, the Trump Administration will drop tariffs. And, now, let the games begin!

As I go to press, the S&P 500 index is down sharply to $5,435, a level it was last trading at … in September! I can remember folks last year worrying that the market would top out at about $5,400 before declining.

Though I'm not an economist, I think I understand the negative possible consequences of tariffs. But, I think it's time for a recalibration of trade. Why should we be the brunt of such unequal tariffs? There is so much hysteria because it seems that most people have no clue about the ridiculously high tariffs against our products while our tariffs have been low. The howling that we hear from other countries is high drama for their own benefits.

I think Trump is using tariffs as a negotiating tool for a number of different reasons. As usual the media has whipped up the hysteria as though bad results are fait accompli. I'd like to wait and see how it plays out.

Yogi Berra: "In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is." In other words, things don't always happen the way the experts predict. We see these failures all the time.

I would argue that the missing part of the lesson from South Korea and similar nations is that export-led growth, with an industrial policy and trade protection, can be successful if (and only if) there are other countries who will buy your exports.

If other countries are all trying to do the same thing, it doesn't work. Plus you need the institutions etc as you allude to.