A Symbiosis of Honor and Victim Cultures: The Schools-to-Prisons Pipeline

A gangland culture of honor may motivate a lot of violence, but an elite culture of victimhood rationalizes the violence, excuses the violence, and enables the violence.

What would Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr have to say about ‘honor culture’?

In my previous employment, I’d make most of my mistakes when scratching out equations and ideas on a pad of yellow, ruled paper. And no one needed to know. Those mistakes ended up in the waste bin.

Every day, late morning, W. would show up to empty the waste bins. Some days featured a non-trivial volume of crumpled, yellow paper. We might take a few minutes to talk about the goings-on in the world. And one day W. had heavy news. Her son had been murdered, “execution style,” as she put it, shot in the head at close range. A charitable rendition of the story, as I tried to imagine it, involved something about the young man standing up for the honor of a young lady. He took a bullet for his efforts.

A couple of other young fellows had done this. They laughed and grinned in the court room at one stage or another of the short, sharp trial. W. found herself evaluating the concept of capital punishment.

Within a year or two, one of the other members of the building service staff had similar news to report. His son had taken a bullet. I don’t have insight into the circumstances that yielded that result, but I did end up with privileged access to information on a host of other such incidences—murders, some of them “execution style”—that unfolded over the course of one ordinary, hot summer. I found myself stuck on a grand jury for five weeks. The grand jury investigated aspects of as many as 80 cases.

My jury dedicated most of its energies to investigating “violent crimes”. Attorneys would bring in witnesses to provide testimony about what they had seen at one crime scene or another. And we, the jurors, would get to ask questions. We did not have a hand in choosing witnesses for grand jury investigation, but we did get to exercise some degree of initiative. The attorneys would select witnesses and take the lead in asking questions. Basically, they were previewing the viability of a prospective case. They’d get an opportunity to hear what jurors were thinking and to see what testimony would either help motivate an affirmative case or help dispose of a case. The attorneys we worked with were very good.

One could not help but notice that very nearly all of the violent crime was concentrated in small enclaves in the city. It is true that one fellow did shoot and kill a neighbor just a few doors down from my own house in Washington, DC—I made contact with that in an essay last month or so—but most of the action goes down in lawless enclaves.

Lawless they may be. Each of these small communities are nonetheless governed. They are each governed by a gang, and governance is supported by norms. The sharing of proceeds from drug trade encourages compliance with norms. The prospect of taking a bullet in the head, “execution style,” also promotes adherence to norms. And that’s what makes these communities governed but lawless: Everyone has an interest in maintaining the status quo. No one has an interest in giving actionable testimony in grand jury proceedings. That could disrupt the corporate peace in the community.

Many of the people in these communities effectively live off of the grid, but most of them have resources. They drive SUV’s, and they know guns. “What kind of guns did they use,” we sometimes found ourselves asking. “One had a MAC-11,” one young fellow once reported. A MAC-11 is, we learned, a fully automatic pistol, a “subcompact” version of a MAC-10. It’s a small machine gun.

The MAC-11 was prominently featured in the 1988 film “Colors.” The film was inspired by the gang warfare between the Cripps and Bloods gangs in Los Angeles. Those gang wars were part of the larger Crack Wars of the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. In the film, an older, wiser policeman (Robert Duvall) finds himself teaching the young hot head (Sean Penn) how to deal peaceably with people who operate out of a gangland honor culture.

The violent crime we heard about in grand jury was almost exclusively really stupid stuff. It’s a hot Saturday afternoon. People start drinking out in a back alley. And this sticks in my mind: They were often drinking Hennessy, cheap, ersatz cognac. Witnesses would volunteer this information: “We were drinking Hennessy.” Quite a crowd would have gathered in the back alley or on the street by evening. By late evening someone chooses to take offense over some sly jibe. That someone pulls a gun and looses off some number of shots. Never mind the fact that the city maintained very strict gun regulations. (All this unfolded before the Supreme Court ruling in Heller v. District of Columbia in 2008. That opinion forced DC to loosen up its regulation of hand guns.) A bystander gets dinged. There are a lot of witnesses. A grand jury thus finds itself with a lot of work to do. Meanwhile, one can only wonder how many thoughtfully premeditated crimes we never got to know about, because, by design, there had been no witnesses. We’d see a lot stupid stuff, impulsive crimes of passion, but little in the way of professionally-executed crimes.

It surely is common knowledge that the incidence of violent crime is not uniformly distributed in the population of the United States. It tends to be concentrated in the lawless enclaves, and most of the victims and perpetrators of homicide tend to be black. The FBI statistics are explicit. (The latest available data come from 2019.) As I had reported earlier in a post titled “Experiences with disarming the public,” of the 13,927 homicides in 2019, at least 7,484 (53.74%) involved black victims and 5,787 (41.55%) featured white victims. See the FBI’s Expanded Homicide Data Table 1 For 2019:

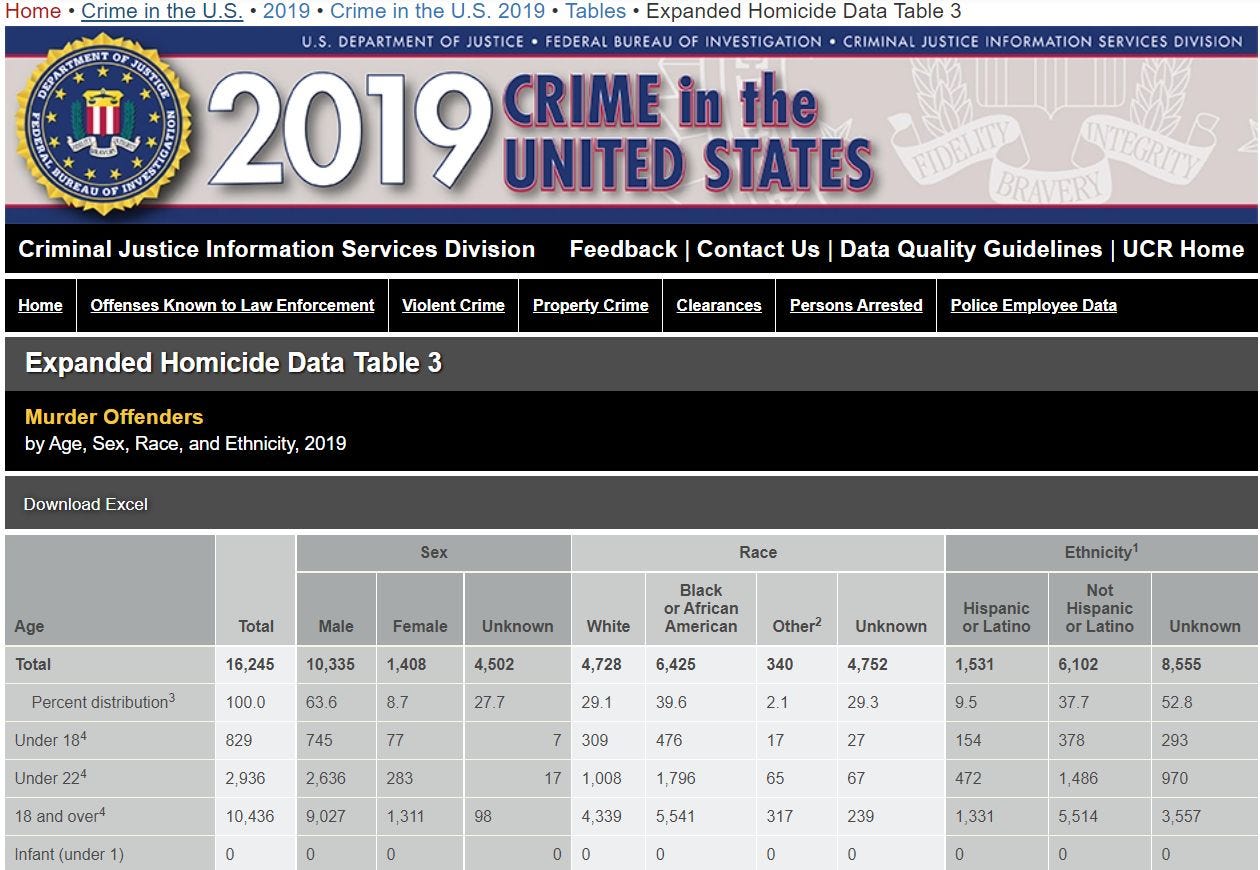

Meanwhile, of the 11,493 identified perpetrators, 6,425 (55.90%) were black, and 4,728 (41.14%) were white/Hispanic. See Expanded Homicide Data Table 3:

Murder is a bad business, of course, no matter who commits it nor who is victimized by it. But it is even more unfortunate that some observers gratuitously racialize these matters. For example, a few days ago, George Soros posted a short piece in the opinion pages of the Wall Street Journal titled “Why I Support Reform Prosecutors” (July 31, 2022). His own motivation was this:

We need to acknowledge that black people in the U.S. are five times as likely to be sent to jail as white people. That is an injustice that undermines our democracy.

There are at least three things going on in this one vague statement:

The suggestion that black people tend to be incarcerated at rates exceeding their share in the population. (Abundantly true.)

The appeal to Our Democracy™.

The suggestion that somehow the fact that rates of incarceration do not align with shares of representation in the population reveals injustice.

What is going on?

Let’s take George Soros’s first point:

Note that black folks make up about one-eighth of the population but comprise more than half of the murder victims and more than half of the murderers.

That said, it is mostly a small cluster of black folks concentrated in the enclaves who are doing most of the killing of other people in their own enclaves or of people from rival gangs’ enclaves. That last bit is what gang war entails.

These same black folks murder all other people—white folks, Hispanics, Asian folks, everyone—at disproportionately high rates. “Disproportionately” would be understating the case.

There are obvious reasons—reasons obvious to anyone who bothers to look—why incarceration rates among blacks have been so high. More violent crime, more incarceration. We should not be surprised.

Now the second point about Our Democracy. I submit that it amounts to an appeal to affluent, mostly white progressives—”Baizuo” (白左) to the Chinese—who live in their own, very secure enclaves. The main proposition (the third point) is wrapped in Our Democracy to make it more palatable and less susceptible to argument. And thus the main proposition:

The fact that blacks are incarcerated at higher rates than whites reflects Systemic Racism™. Society drives young black people—mostly young black men—to do desperate things. They grow up disadvantaged, and thus end up more likely to do bad things. And, then, after having done bad things, they get swept up in a judicial system that makes no allowance for Restorative Justice™.

It gets worse. Young men may get swept up into the system after having fathered some number of children. The children end up denied the advantage of growing up with their fathers. The cycle of disadvantage continues.

This purported dynamic is much the subject of Pipeline, a play put on by the Studio Theatre in Washington, DC in 2020.

Nya, a public school teacher at an overcrowded and underfunded city high school, writes the words of Gwendolyn Brooks’s 1959 poem “We Real Cool” on the board for her students. What was once her favorite lesson plan has become an anxiety trip as the poem now has a face: that of her seventeen-year-old son Omari. Nya believed that she had saved him from the school-to-prison pipeline when she and her ex-husband Xavier sent Omari to a majority white boarding school upstate. However, when she gets a call from the school informing her that Omari got into a fight with his English teacher during class, she worries that Brooks’ prophecy of doomed youth is about to come true.

“School-to-prison pipeline.” The progressive media has worked hard to normalize this phrase. Young black people had tended to be subject to disciplinary action in the public schools at disproportionately high rates, because all those pink-haired, progressive public school teachers were operating out of their implicit biases against black people. On top of that, the schools are under-funded, notwithstanding the fact that the public schools in the United States spend multiples more in real terms per student than they had 50 years ago—albeit with no improvement in measures of student performance.[1] And the United States spends more per student than other countries, and yet American students still lag many of their less well-funded foreign peers.[2]

Just punching “Schools-to-prisons pipeline” into any search engine will yield any number of lugubrious, presumptuous “explainers” of the sort that our friends at Vox or the ACLU routinely put out. From the ACLU:

For most students, the pipeline begins with inadequate resources in public schools. Overcrowded classrooms, a lack of qualified teachers, and insufficient funding for “extras” such as counselors, special education services, and even textbooks, lock students into second-rate educational environments. This failure to meet educational needs increases disengagement and dropouts, increasing the risk of later court involvement. (Emphasis in the original.)

In 2014, the Department of Education under the Obama Administration put out one of its infamous “Dear Colleague” letters. An earlier such letter to the universities in 2011 advocated for upending due process in sexual harassment processes on campus. The 2014 letter advocated explicitly for “restorative justice” in the public schools. The idea here is that the public schools may have implemented policies and processes for dealing with disruption in the classroom, and implementation might be “color-blind,” non-discriminatory. But, the Department of Education averred that evidence of “disparate impact on the basis of race” might constitute violations of federal law. Basically, evidence that black kids were disproportionately subject to disciplinary processes by virtue of color-blind application of those same processes could yet make big trouble for the schools. Better it would thus be to apply less stringent standards to black kids as a whole in order to diminish the rates at which black kids were disciplined. The administration demanded that the schools implement discriminatory policies, not anti-discriminatory policies, in order to impose a kind of equality-of-results. No surprise it would be to find that the classrooms subsequently became more disruptive and dangerous.

Talking to public school teachers can be illuminating. I can’t pretend to have assembled a representative sample of interviews, but some teachers have related incredible stories. One fellow I’ve met has taught history and civics at some of the schools in my area. He reported that an enterprising young lady had organized a prostitution ring at one school—at a middle school, meaning the young girls who participated were really young. Like 13. Maybe 14 at the oldest. And who comprised the clientele, I asked? Men in the neighborhood. Some number of the boys, too. Unbelievable. And that was just one of his stories. Other stories involved dealing with physical threats from students in the classroom. But what can one do when the school administration is committed to restorative justice, which is just a euphemism for not dealing with the physical threats? Teachers end up being bullied by young people who have no business being in the classroom. They get demoralized. And talented, thoughtful people leave and end up as Uber drivers.

Here’s a question for George Soros. Has application of “disparate impact” doctrine helped create an actual schools-to-prisons pipeline where none had existed before? And, if there had not been one before, what could explain the vivid evidence of disproportionately high violence and crime within certain communities?

It would hardly be novel to appeal to the idea that certain communities, infused with a culture of “honor,” tend to be more violent than those ordered by a culture of “dignity.” (This 2015 piece in the Atlantic makes for a reasonable place to start.) An “honor culture” creates demand to publicly and ostentatiously redress perceived slights. Hence, shooting up a block party on a sultry Saturday evening after being the subject of an insult, real or imagined. Or, a cluster of young men pulling out their MAC-11 automatic pistols and ambushing another cluster of young men in order to redress (or, rather, to aggravate) an ongoing “beef.” In contrast, “dignity culture” creates demand to not make a big deal of small slights. Be a real man by not being so goddamn sensitive. Save escalation for another time if and when a time comes for escalation.

The honor/dignity dichotomy would seem to make for a promising avenue of further inquiry. Some researchers have done just that. The dichotomy could also motivate an explanation for the “disparate” outcomes in the classroom. But some observers suggest that, these days, there may be another culture at work, a culture of “victimhood”. And I would pose this modest innovation on the idea: Certain enclaves may be infused with a certain culture of honor. The honor culture may motivate violence. But, certain outside observers, comfortably ensconced in their own, secure, affluent enclaves, may view the violence through the lens of victimhood. From the victimhood perspective, the people committing such violence do so because they are victims. They are victims of a systemic racism and thus should be lifted up through a program of restorative justice.

By this view, people like George Soros and other affluent progressives project a concept of victimhood on the people on the street. They condescend. Oddly, the people on the street may not perceive themselves as victims, for that would be incongruous with their honor culture. But they do end up victimizing a lot of people who operate within that honor culture. Progressive elites end up both excusing and enabling that actual victimization. Their programs of restorative justice amount to solutions to problems (systemic racism) that only exist in their own minds.

[1] I don’t have time right now to fully run this point down, but I will refer the reader to this piece from the Manhattan Institute as a starting point: Max Eden, “Issues 2020: Public School Spending Is at an All-Time High,” July 25, 2019 at https://www.manhattan-institute.org/issues-2020-us-public-school-spending-teachers-pay.

[2] https://rossieronline.usc.edu/blog/u-s-education-versus-the-world-infographic/

So it might appear that progressive effort allows themselves to feel OK but forces others to become victims. Schools should have high, not low, expectations for students with extra help for those that struggle. Allowing any misbehavior gets more of it. Sadly many kids just seem to have given up, just getting by because nobody thinks they are worthwhile. Lectures on how bad off they are has no positives.

Change "school" to society and see where we are.