Experiences with disarming the public - The Hideyoshi 'Sword Hunt'

Would restricting access to weapons induce Le Chatelier effects (and, hence, reductions) in violence and homicide?

The farmers of all provinces are strictly forbidden to have in their possession any swords, short swords, bows, spears, firearms or other types of weapons. If unnecessary implements are kept, the collection of annual rent may become more difficult, and without provocation uprisings can be fomented…

That was Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Japan in 1588. Japan had been fractured for most of a century, as regional samurai factions had fought for dominance. Nobunaga had yet come close to concentrating the country under unified leadership. His lieutenant Hideyoshi finished the job. His victorious faction then set about imposing a new administrative regime. That regime, if not the particular factions running it, would remain intact until the late 19th century.

The dominating feature of the new regime was the formalization of a hierarchical caste system. It was almost like something pulled out of Plato’s Republic. Merchants occupied a place far down the hierarchy, because it was not obvious that their wheeling and dealing generated much social value. Artisans occupied a place one step up. Further up came the samurai, the people who actually ran the regime, but just below them were the farmers, a caste that occupied a place of some esteem, because their produce constituted the principal source of the country’s wealth.

On my reading, the regime operationalized a theory of the “wealth of nations” that had some of the flavor of the French Physiocrats’ concept of wealth creation: wealth literally came out of the ground in the form of agricultural produce. All other occupations involved transforming that wealth into other goods and services and distributing that wealth through the economy. The ultimate purpose of operationalizing that theory, however, was to maximize tax receipts. Those taxes were manifest as fixed portions of rice output measured in koku. Each agricultural plot had to come up with a fixed volume of rice each year, even in bad years. The new administration even went so far as to rate the relative productivity of rice-producing properties and to assess tax burdens accordingly. Like the Normans under William the Conqueror post-1066, the administration had to survey the lands. The farmers of more productive plots would bear higher tax burdens per unit area. The farmers of marginally productive plots would bear lower tax burdens. But, either way, farmers would bear risk in that they would enjoy the upside of good harvests but would have to absorb the downside attending bad harvests. At the end of every season, the central authorities would get their fixed volume of tax receipts. Hence the motivation, one might guess, for the great “Sword Hunt”: It was not so much the public that was barred from owning certain weapons—in the beginning, at least. It was the farmers who were barred from owning weapons, for these were the people who comprised the tax base and bore the risk of making it work. These people had to be disarmed.

So, to recount: Hideyoshi’s faction finished the long-running project of reuniting Japan. Hideyoshi and his lieutenants then gathered around a table, traded cups of sake, and contemplated what they were going to do. They decided to implement a feudalistic New Deal. The starting point was the question of how to generate revenue—tax receipts. They’d survey the agricultural productivity of the country, plot by plot, and then assign tax burdens. The “Sword Hunt” and formalized caste system were merely measures to protect the tax regime from the tax paying peasants who might otherwise rise up in rebellion.

Meanwhile, one can imagine that basing taxes on “share-cropping” in place of a system of fixed payments measured in koku could have mitigated the prospect of rebellion in the countryside. Share-cropping would have enabled the central authorities to relieve farmers of some of the downside risk or poor harvests. Indeed, one can also imagine Hideyoshi’s people puzzling over the relative merits and demerits of different tax schemes, but the one great advantage of a fixed-payment scheme is that the authorities would have less reason to bear the costs of monitoring total output. Under a share-cropping scheme, farmers might be tempted to cheat by under-reporting output. But, under a fixed payment scheme, farmers have little capacity to cheat. It’s not even obvious that they would even have to bother reporting total output. All that the tax authorities would care about is getting their fixed payment regardless of agricultural yields. One could yet imagine a farmer demanding tax relief in the face of a particularly bad harvest. The authorities might then be compelled to investigate, but, in the normal course of business farmers need not misreport output, and the authorities need not bother audit output. Everyone would be relieved of a lot of paperwork. The costs of running the tax system would remain low.

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 marked the beginning of the end of the rule of the samurai and of the de jure caste system. The how and why of it is a little puzzling, but one can imagine some of the motivation. The samurai ruling class had been collecting its fixed rent (taxes) for about 250 years, but there had been little demand for its military services. One can also imagine that renewed contact with the West and the prospect of industrialization would radically change the composition of economic activity. The old scheme of taxation, if not administration, would itself have to be radically changed, because agriculture would assume a diminishing share of total economic activity. Finally, one can imagine that the caste system became maladapted to economic developments, for it was before this time that great merchant families with names like Sumitomo and Mitsui had already assumed great prominence if not high rank. During the Meiji years, they were joined by families with names like Mitsubishi and Yasuda. The Japanese economy was being folded into a globalized economy. The old ways and the old interests were no longer dominant.

The samurai themselves lost formal recognition as a distinct class in 1876. Even so, it was that same class of samurai that had populated the administrative state of pre-Meiji Japan that went on to largely populate the administration of the actual Meiji Japan. Perhaps the administration did not change much after all, at least in spirit.

Contrast the motivations for Hideyoshi’s Sword Hunt with the demands to maintain “a well-regulated militia.” Have not all countries had to face the problem of how to raise men-at-arms for both the defense of the country or for the king’s adventures abroad? Not in the Japan of 1588, it seems. The ruling clique seemed to have understood that, having consolidated Japan under unified leadership, it could get by without having to rely on reserves of yeoman farmers to do its fighting. And, early on, it did much fighting, invading Korea in 1592 and again in 1597. It was up to the farmers to stay home and raise taxes to fund such ventures. It was also up to them to not rise up in rebellion. Meanwhile, much legend and lore attend the British longbow tradition. The battles of Crécy (1346), Poitiers (1356), and Agincourt (1415) may first come to mind. But one did not randomly recruit men-at-arms much less longbowmen. Longbowmen, for example, cultivated themselves from a young age like any serious athlete in training. The skeletal remains of archers exhibit evidence of the repetitive stresses of pulling a few hundred pounds of weight.

The English (and the Welsh and the Scots and Irish) seemed to have encouraged the general population to develop skills in the martial arts, notwithstanding the fact that these countries experienced any number of rebellions and civil wars, at least through the 17th century. The Jacobite rebellion of 1745-46, the stuff of “Scotland the Brave” against “England the Strong,” marked the last sustained uprising until, perhaps, the fight for Irish independence right after World War I. There surely were important episodes of violence in England itself post-1700, but there was nothing quite as spectacular as the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. In that matter, Wat Tyler assumed leadership of a sizable mob that went so far as to ravage London before King Richard III managed to bring in troops to crush the uprising. So. Given the fact that the peasants could revolt, what did the authorities do, if anything, about disarming the general populace, or would that kind of thing have been too costly or impractical to implement? Did the authorities ever consider disarming its class of farmers?

A self-deprecating Abraham Lincoln reported that his greatest honor was to have been elected captain of a company of Illinois militia in 1832. His unit mustered a few times in anticipation of action in the Black Hawk War of the same year, although his unit never saw action. But note what his unit was: a cluster of actual yeoman farmers, all proficient with the firearms of the day, who could be expected to come together and coordinate collective defense when and if demands for defense became manifest.

One might be thinking that that is the kind of thing that the Second Amendment to the Constitution contemplates. The reality, of course, is that the modern interpretation of the Second Amendment, as articulated in the Supreme Court opinion in Heller et al. v. District of Columbia (2008), deemphasizes the collective right to self-defense by bearing arms and elevates an individual right to self-defense by bearing arms. Practically speaking: The states, not the federal government, have historically assumed the principal role in regulating access to things like firearms and abortion. The opinions in Roe v. Wade (1973) and Casey v. Planned Parenthood (1992) basically said that states have to provide some level of access; the states can’t regulate abortion access into oblivion. Similarly, Heller (2008) said that the states have to provide some level of access to firearms; the states can’t regulate access to firearms into oblivion.

Societies have long puzzled over how to regulate—if to regulate at all—access to weapons and abortion. In an earlier piece I talked about how even the Catholic Church of the 7th century, Dark Ages Europe seemed to have assumed a surprisingly modern and pragmatic orientation with respect to abortion but also to such grievously unspeakable things as infanticide. In that same piece, I made some contact with the regulation of firearms.

Societies have also grappled with the problem of how to deal with mentally disturbed people. This kind of thing also comes up whenever there is “mass” gun violence. But, not so much with respect to other violence such as the constant weekly boil of 40, 50 60 shootings in places like Chicago or Baltimore. Why is that?

I ask, because, should we not concentrate our attention on deadly violence, by whatever means? Instead, media attention concentrates on “mass” killings involving firearms. One very good reason, surely, would be the fact that firearms really are implicated in most mass killings. But not all mass killings involve firearms. For example:

People do set off bombs—think Timothy McVeigh and the bombing the federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995.

The authorities themselves have managed to kill people en masse. In 1993, for example, the US Treasury Department’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) raided the Branch Davidian compound near Waco, Texas and managed to kill 76 people. The authorities sprayed the site with bullets, but it was a great fire which took the greatest toll. That toll included as many as 20 children, notwithstanding the fact that the Attorney General of the United States, Janet Reno, vigorously protested after the fact that the purpose of the raid was to secure the welfare of those same children.

Then, of course, there are the events of September 11, 2001. Flying fully-fueled passenger jets into buildings took a spectacular toll—but not nearly as spectacular as it could have been, since as many as 50,000 people worked in the “Twin Towers” (the World Trade Center in New York). It was a blessing, really, that the terrorists implemented their strike in the morning, well before most people had showed up for work.

Then there are events like the murder-by-arson at an anime studio in Kyoto, Japan in 2019. At least 35 people perished.[1]

All that said, we can all imagine that firearms occupy most of our attention for at least one very good reason. It is reasonable to suggest that firearms lower the costs of killing a lot of people in a short span of time. That’s just the kind of technology that might induce a prospective mass killer to become an actual mass killer. One doesn’t have to belong to a sophisticated, well-armed and well-funded terrorist network—or federal agency—to inflict a lot of harm. And we all have an intuitive sense that the Le Chatelier Principle is at work here. (Basically, if we impose a constraint on how people can economically organize certain activity, and if that constraint binds, then we get less of that activity.) So, if shooting people is an economical way to kill people en masse, then frustrating access to firearms should yield fewer mass killings. But, let me suggest that it could make sense to partition gun violence into at least three sets: mass killings, the steady simmer and boil of gang warfare, and quasi-random victimization of people who are not involved with gangs. Insofar as Le Chatelier effects obtain at all, where are they concentrated?

My own intuitions tell me that (1) Le Chatelier effects are very prominent with respect to mass killings conducted by genuinely disturbed individuals. The business in Uvalde, Texas a few weeks ago and the business in Buffalo, New York a week before that are obvious candidates. (2) Le Chatelier effects might even inform the dynamics of gang warfare. Gang members conduct “drive-by shootings” for a reason: they can strike targets quickly and abscond before anyone can organize a defense and retaliate. Alternatively, what are the dynamics of gang warfare when everyone knows that everyone is armed? Might a countervailing effect be operating in that gang members perceive advantages to maintaining a tense peace over “going to the mattresses” or getting caught up in constant, low-grade warfare. And then (3): When it comes to victimizing people “up close and personal,” do Le Chatelier effects really inform what is going on? Is it to this class of violence to which the “individual right” to self-defense by firearms really speaks?

Intuitions are important, but it would be good to make them stand up to the discipline of empirical analysis. Basically, can we do a “comparative-static” analysis that would allow us to get some idea about whether particular types of people, gang members or non-members, say, would be safer in an environment featuring low access to firearms in contrast to an environment characterized by greater access to firearms? Can we get a grip on the performance of a high-access equilibrium versus a low-access equilibrium? Stated differently: The New York Times followed up the mass killing in Kyoto with a catalogue of “mass killings” in Japan.[2] One might expect that the data would show that mass killings defined by almost any measure have been more frequent in the United States. (Have they been more frequent?) But we would really like to examine the total volume of homicide, not just arbitrarily defined “mass shootings.” Basically, do high-access societies generate a higher volume of killings than low-access societies, and can we distinguish differences between gang violence, quasi-random, individualized violence, and mass killing events? For example, do prospective perpetrators exercise some forbearance in environments in which they can expect other people to shoot back and defend themselves?

One can imagine that a kind of “fixed effects” analysis might go some way toward furnishing a plausible answer to the question of the net effects (if any) of access to firearms. Surely some societies are simply more violent than others. Canadians, looking south of their border, would certainly agree to that. We might yet find that Mexico, El Salvador, Somalia—maybe even Brazil—exhibit more violence than the United States. Conceivably, we could filter out a lot complex differences between countries and disentangle the effect of differential access to firearms by tossing country-specific dummy variables into a regression equation. That sounds promising, but then we would have to look for variation in violence and variation in access to firearms over time in individual countries. The idea is that a given country might exhibit a baseline level of violence, and we could filter that out. We would then like to see if violence varies with changes in access. But, is there really enough variation in the data to help us see what is going on?

The real issue might prove to be getting a hold of good data. That’s always the biggest problem. There are all types of analyses we would like to do, but getting data can be hard. And that is a great shame, because, without data, observers can continue to advance their own grand narratives about how the world works without ever having to face up to the discipline of empirical analysis. That said, we might find that there is only small amount of data from a select number of countries that might enable some quasi-experiments. Data pre and post the “Dunblane Massacre” (Dunblane Scotland, 1996) might useful. My understanding is that gun access became much more restricted post-Dunblane. Did overall violence subsequently decline?

I note that there is much variation over the last 60 years in the United States in the incidence of violent crimes. The murder rate, for example, peaked in the early 1990’s and then drifted down to levels not experienced since the early 1960’s by the year 2000. One would hope that such data would yield some of its secrets, but criminologists have had a hard time explaining the rise and then fall of such crime, although various observers have their politically favorite theories. One popular theory, attributed to Steven Levitt of “Freakonomics” fame, is that abortion became widely available post-Roe-v-Wade in 1973; women ended up having fewer “unwanted children”; these children would have been prime candidates to grow up into tomorrow’s killers. Thus, fewer unwanted children. Less killing. That’s the theory. Meanwhile, murder rates have been increasing since 2014, so, it’s not obvious that the abortion hypothesis, however earnestly maintained by its very earnest proponents, holds up in the data.

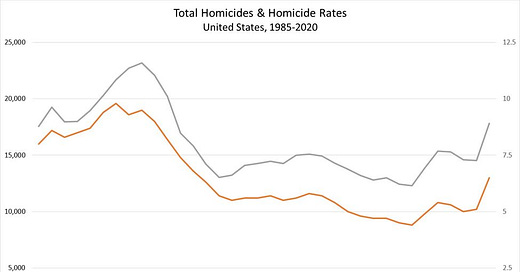

Many years ago, one could easily access from the FBI annual crime statistics going back to 1960. It is from those data that I know that homicide rates in the year 2000 looked like crime rates pre-1965. But, during the Obama years, the FBI started to bury certain data. One can now get ready visibility to certain numbers going back only to 1985, because “Open Government.” That said, here is a graph that indicates homicides-per-100,00 and total homicides in the United States for the years running from 1985 through 2020.

Over these years, homicide rates reached a nadir of 4.4 per 100,000 in 2014. In 2020, these rates have returned to mid-1990’s levels, and there is no reason to expect that they have not continued to increase in 2021 and 2022. Firearms were implicated in at least two-thirds of homicides in each year, and handguns accounted for about 90% of those homicides year to year (in the subset of cases in which type of firearm was indicated). See the following table below from the FBI.[3] Rifles, which would include rifles that have been cosmetically manufactured to look like “assault rifles,” account for 3% to 5% of homicides involving firearms (in the set of cases in which type of firearm was indicated). So, rifles do not appear to be where the big action is. Handguns are where the big action is. But, we can imagine that rifles show up disproportionately in “mass” shooting events and that handguns dominate gang war killings. It would be nice if we could tease out such subsets in the data.

Meanwhile, of the 13,927 homicides in 2019, at least 7,484 (53.7%) involved black victims and 5,787 (41.6%) involved white/Hispanic victims.[4] The same FBI dataset enumerates 16,245 perpetrators. Of the 11,493 identified perpetrators, 6,425 (55.90%) were black, and 4,728 (41.14%) where white/Hispanic.[5]

The FBI data do provide some insight into who is killing whom, at least with respect to killings that involve a single perpetrator and a single victim. In 2019, these one-on-one homicides accounted for 6,578 or 47.2% of all homicides.[6] These data would surely feature a lower proportion of gang-related activity and a higher proportion of quasi-random, individualized events. More than 78% of the individual white/Hispanic victims were killed by other individual white/Hispanic people. More than 88% of black victims were killed by other black people. So, evidence of “black-on-black” crime remains. So does evidence of white-on-white crime. What is not indicated in these data, however, is the fact that blacks account for 13% of the population. Year to year, more than half of the murders and more than half of the murderers are concentrated on one-eighth of the population, and surely all that homicide is concentrated within a subset of that 13%.

Homework assignments for the FBI and for criminologists who maintain privileged access to data:

If I were king of the world, I’d invite the authorities to stop harping on selected categories of crime and to step back and analyze the universe of violent crime. I’d ask them to come up with answers to these (and other) questions:

Are mass shooting events subject to Le Chatelier effects—that is, would restricting access to firearms sharply reduce the incidence of mass shooting events?

Would restricting access to firearms ultimately reduce the incidence of mass killing events?

Is gang violence subject to Le Chatelier effects, or does forbearance—interests in keeping the peace—dominate such effects?

Would restricting access to firearms ultimately reduce the incidence of the sum of gang violence?

Is one-on-one, quasi-random violence subject to Le Chatelier effects, or does the prospect of getting shot discourage an appreciable volume of violent crime?

Would restricting the access of the public to firearms increase or decrease the use of firearms on the part of federal, state and local authorities?

Would restricting the access of the public to firearms increase or decrease the application of violence on the part of federal, state and local authorities?

1] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2019/07/27/national/crime-legal/death-toll-arson-attack-kyoto-anime-studio-rises-35/

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/17/world/asia/japan-fire-animation-studio.html

[3] https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/tables/expanded-homicide-data-table-8.xls

[4] https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/tables/expanded-homicide-data-table-1.xls

[5] https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/tables/expanded-homicide-data-table-3.xls

[6] https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/tables/expanded-homicide-data-table-6.xls

One of the issues about the current popular rifle weapon is how easy it it is to use and shoot. That seems a factor by these shooters. And while the bullets generally are better at maiming rather than killing, enough of them cause death. Still they are in widespread use so removing them is impractical. Aside from the commonality of the weapon, there is a commonality in the persons where we might be able to do something about.