This is a tale in four graphs. But first, this dispatch from the October 13, 2020 meeting of the Wise County School Board:

In-Person Learning Update

[Superintendent] Dr. Mullins shared that the in-person learning option started on Monday, September 28, 2020 with a four-day per week schedule. Instruction has gone very well. I am extremely proud of our students and staff for their efforts to follow the suggested [COVID] mitigation strategies. At this time, our enrollment is 5253; we have 2023 students who have elected the all-virtual learning platform.

The Wise County school system opened the 2020/21 school year with four weeks of “all-virtual” instruction but posed the option, if not the requirement, of traditional, in-person instruction on September 28, 2020. Seventy-two percent of students opted for in-person instruction.

Meanwhile, in Richmond, Virginia, the schools remained closed to in-person instruction, and they remained closed until the state legislature (comprised of the State Senate and the House of Delegates, both dominated by the Democrats at that time) voted overwhelmingly to require all Virginia public schools to offer in-person instruction for the following school year (2021/22).

Over the last day I have managed to secure from disparate sources, including the Virginia Department of Education, data that would allow me to calculate spending per student by district over the course of many school years. I have also managed to secure data on the proportion of students who had opted for full-time, in-person instruction in each school district.

In my post of August 28, I had tuned up a variable to serve as a proxy for enthusiasm, district to district, for opening up to in-person instruction after the advent of COVID. That proxy variable was the proportion of votes in the 2021 gubernatorial election that went for the Republican candidate, Glenn Youngkin, over the Democrat, Terry McAuliffe. That variable exhibited a surprising degree of explanatory power. But, one would expect that that this new metric—the share of students attending in-person—would serve less as a proxy and more as a direct indicator of the enthusiasm in a given school district for in-person instruction. That said, the decision to attend in-person or to avail oneself of remote, online instruction, is just that: a decision. It is a decision that may be informed by a whole host of factors including constraints imposed by school districts or the state itself. Recall that the state of Virginia itself had required all schools to close to in-person instruction through the entire spring of 2020. But, in the following school year, some school districts (like Wise County) were more liberal about providing options. Other districts (like the City of Richmond) were intent on imposing no option for in-person instruction indefinitely. In the summer of 2020, for example, the Richmond School Board opted to implement a “virtual-only option” for the coming new school year. The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported:

The 8-1 vote [of the school board] came after an overwhelming push from teachers. Two teachers started a petition that demanded the board not vote on July 9, when it was originally scheduled to decide on fall plans. The Richmond Education Association, the local teachers’ union, called for 100% virtual learning in a letter to the board. Then teacher unions across the region followed suit.

In some school districts the teachers’ unions may have been more assertive about indicating a preference for indefinite shutdown. And the same may go for parents in certain locales. But, not in others. In others, parents may have perceived advantages to the schools taking up their traditional job of warehousing children through the course of the working day. That may sound a little uncharitable, but busy parents up and down the income scale may have been more inclined than others to pack their kids off to school.

In a succeeding post, I will make some contact statistically with the decision to take up the option of in-person instruction. But, for now, I will note that in-person instruction aligns surprisingly tightly with the proxy variable (the share of the Youngkin vote by county) but appears not to be informed by median income by county. It does not appear that wealthier people were more likely to opt for remote instruction by virtue of, say, being better equipped to accommodate the demands of remote instruction. Rather, it really just looks like some people had more fear of COVID. Others did not. Those who did not were more likely to pack their kids off to school. I also note that schools that offered in-person instruction really did outperform those school districts that discouraged in-person instruction. It was no contest. A question is: Is there a causal relationship there, or is this robust correlation no more than a correlation?

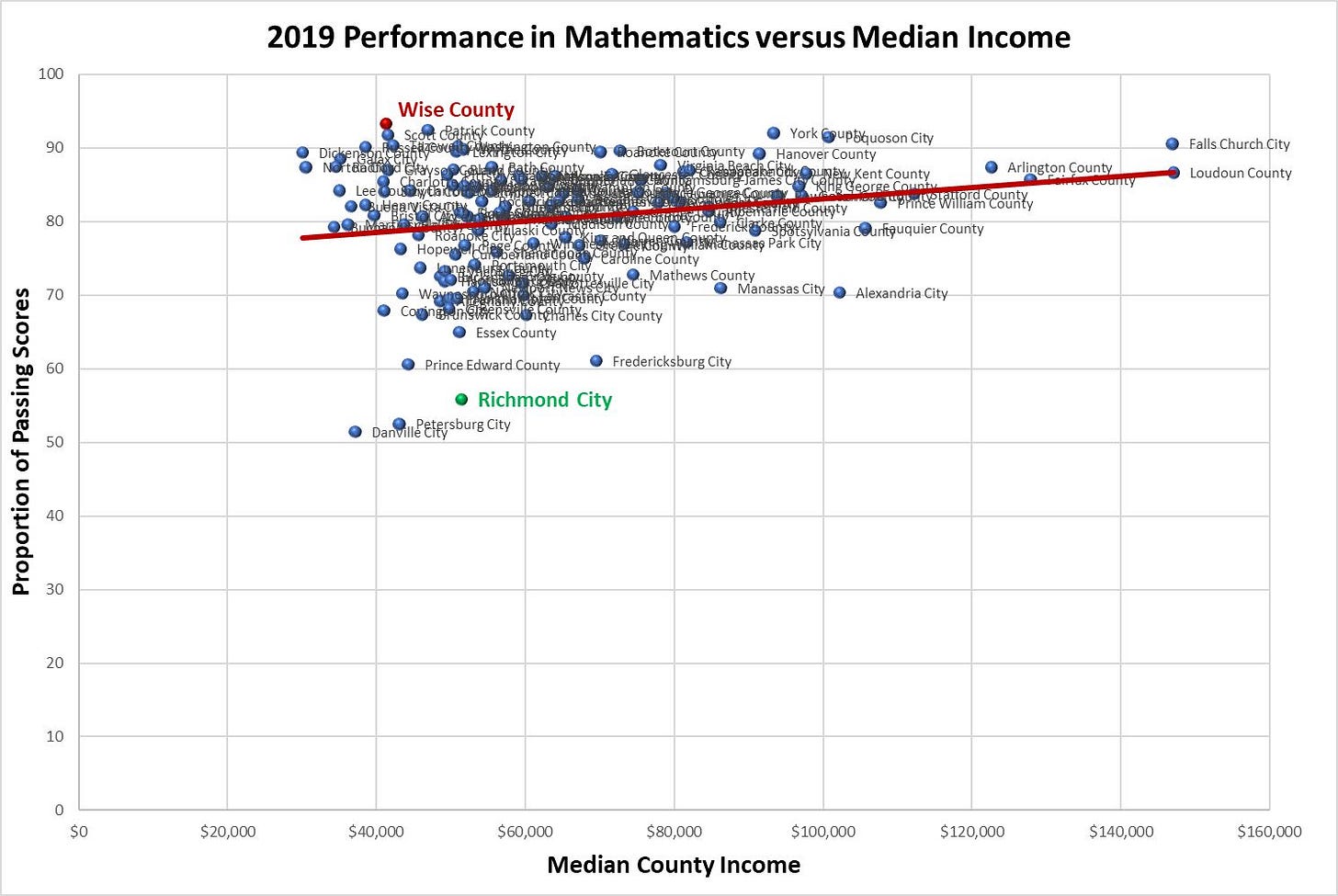

Let me put down the very big question of causation-versus-correlation and take up a multivariate analysis by means of a sequence of four graphs. The first maps performance on the annual mathematics “standards of learning” (SOL) exam in Virginia in 2019 (pre-COVID). That graph maps median county income against the proportion of passing scores (by county) on that exam:

Wise County shows up among the highest performing school districts whereas Richmond City ranks among the three lowest performing school districts. Both districts rank towards the lower end of median income in 2019, pre-COVID. Meanwhile, the red line indicates a positive and non-trivial correlation between median income and performance. There is much variation; poorer school districts do not have to perform more poorly by virtue of being actually poorer than most other counties, but being wealthier makes a difference. Indeed, relatively poor Wise County outperforms the two wealthiest school districts in Virginia (the city of Falls Church and Loudon County).

Let’s now look at performance in 2022 (post-COVID), one year after all school districts will have had more experience with their new remote and in-person instruction protocols.

The solid red line indicates the 2022 trend, and the dashed red line indicates the 2019 trend. The fact that the trend lines both have positive slopes means that, on average, wealthier school districts have performed better than poorer districts, but the 2022 trend line is markedly lower than the 2019 trend line. Thus, on average, the universe of school districts performed worse. (It turns out that all districts did not perform as high as their 2019 benchmarks. Never mind lower performance “on average.” Performance was lower absolutely across the board.) But, note that the 2022 trend line is steeper. The decline in performance was less severe at the high-income end than at the low-income end. But, not by much.

Now let’s look at the 2019 scores again, but this time let’s pair them up with the proxy variable, the share of the vote in each county that went for the Republican candidate in the 2021 gubernatorial election.

Wise County and Richmond City are situated near opposite ends of the political spectrum here. But, again, there is a positive correlation featured in this graph. Performance tended to be higher in the “red” school districts and lower in the “blue” districts. But, not uniformly. Falls Church and Loudon County, both right outside Washington, have been very blue and high-performing.

Let’s look at 2022:

Again, red counties have, on average, outperformed blue counties (the slope of the solid red line is positive), and the red trend line is a little steeper than the dashed line. The increase in the steepness indicates that the decline in performance was more severe among blue counties, but the difference is modest.

In assembling data for this essay and for the previous post, “Profiles in Resilience,” I have come to better appreciate how elusive and complex underlying phenomena are. One obvious policy-relevant question pertains to the relative efficacy of remote, online instruction and in-person instruction. Does one mode of instruction dominate the other? Do the data we have since 2019 enable us to address this question?

The answer might seem obvious, but I would suggest that the answer remains elusive. Specifically, the data we have on the performance of Virginia school districts span four phases:

Before March 2020: Pre-COVID, when one might reasonably expect schools to be operating in a mature system of in-person instruction.

March – June 2020: The immediate experience right after the advent of COVID when the state forced all the schools to move from in-person instruction to remote, online instruction.

The 2020/21 school year: Schools could exercise the option of offering in-school instruction.

The 2021/22 school year: The state mandated that school districts include in-person instruction in their menus of options.

This four-stage sequence does not, I would suggest, amount to a clean experimental design. It really does not enable a clean test of the proposition that remote instruction is strictly inferior to in-person instruction. Why? One could reasonably argue that schools were not situated to implement mature online processes when faced with a mandated shutdown in 2020. For one thing, the state suspended the annual “standards of learning” assessment in 2020; we don’t have data on performance in the immediate aftermath of COVID. But, would we be surprised to see that performance had declined precipitously across all school systems? Even so, one can see that the performance of all schools declined between the 2019 assessment and the assessment of the following year (2021). But those data from the 2021 assessment do not afford a clean test, because there is important self-selection going on: Not all schools opted to offer in-person instruction. Perhaps those schools would yet have done just as poorly had they opened?

Then there are dynamic effects to consider. I’ve already mentioned “mature online processes.” Were schools really situated to implement mature processes when they were required to shutdown, or were they going through a lot of important learning-by-doing? And then there is the question of lost student learning. Performance may have improved between 2021 and 2022 when all schools were required to offer in-person instruction, and, for the most part, schools have yet to meet or exceed their 2019, pre-COVID performance. Students may have experienced lagged effects of lost learning? Moreover, the improvement that students have exhibited may not derive from the shift to in-person instruction necessarily.

The best test in the data may be the shift from the third stage to the fourth stage. In the third stage, schools were allowed to offer menus of remote instruction, in-person instruction, and some combination of the two. Yet, in 2021/22 (the fourth stage), they were required to offer full-time, in-person instruction. Performance improved markedly, but would performance have yet improved had schools been allowed to continue to offer their different menus of remote instruction and in-person instruction? Basically, the idea would be that the school districts were unconstrained in 2020/21. We then impose a constraint in 2021/22. That constraint forces some number of schools to expand their modes of instruction. We yet see an improvement in performance—but we see improvement, on average, across the universe of schools. Can we yet identify an “in-person instruction” effect? In doing so, do we have to worry about dynamic effects? Perhaps students really did require more than one year of instruction after the initial shock of the COVID lockdowns to recover much of their lost ground. Would they have made up that ground with or without the requirement to move to in-person instruction?

To get a grip on the self-selection problem, I may explore multivariate analyses that explicitly recognize the four stages of the COVID experience and use the red/blue variable (the Youngkin vote share) as an indicator of enthusiasm (or lack of enthusiasm) for proactive COVID mitigation policies. We will see what I come up with in a successive essay, but the early indication is that the differential in performance between a school system that offered no in-person instruction in 2020/21 and one that offered the option of in-person instruction could be exceed 30 points. But, for now, I will get back to the tale of two school districts. That is, I will get back to a tale of two data points and will reserve analysis of the universe of 130-plus school districts for the next essay.

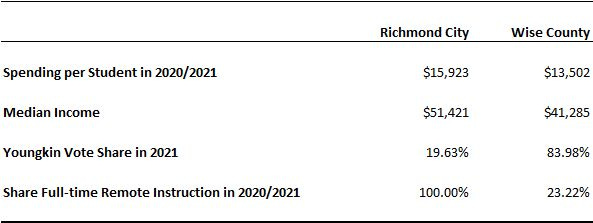

Here is how Richmond and Wise County match up in the data:

Richmond Public Schools (RPS) –

RPS was very enthusiastic about appealing to CDC guidance with respect to COVID mitigation, and to this day, the RPS leadership still makes an ostentatious point of being concerned about COVID. Here, for example, is a screen shot from August 29 of the RPS splash page:

All the kids are dutifully masked. The schools are “Going Green!” RPS is all in on “social and emotional metrics.”

In the 2020/21 school year, RPS imposed 100% remote, online instruction; it offered no in-person option. The only other school system to have imposed 100% remote instruction was Portsmouth County. Both school systems occupy places well below the trend lines in the graphs above.

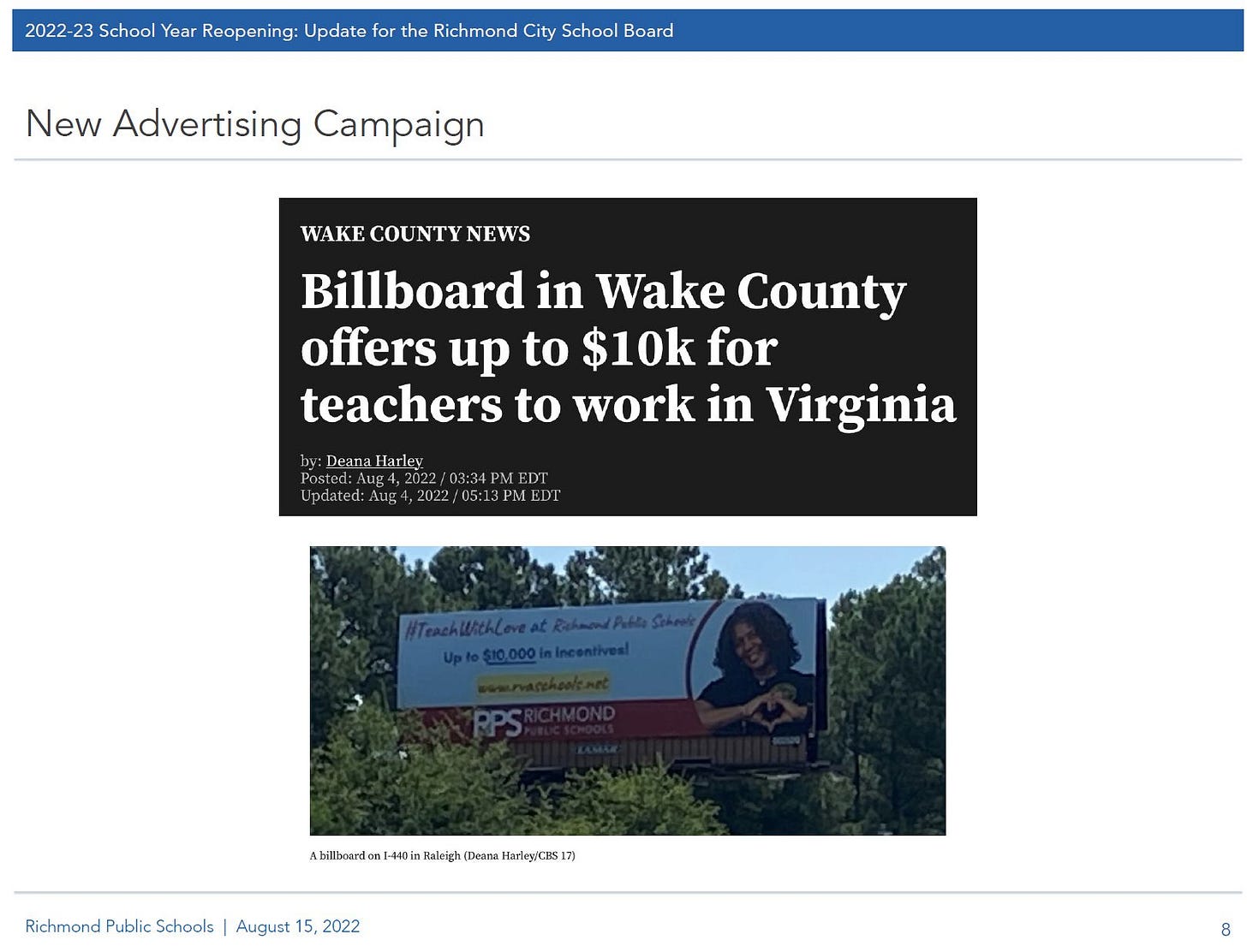

Staffing problems surely are not unique to RPS, but the school system does seem to be putting up with severe shortages of teachers, and it has launched a campaign to recruit teachers from as far away as Raleigh (Wake County), North Carolina:

One may guess that the roll out of RPS’s “Vaccine Mandate” in the 2021/22 school year may have aggravated staffing problems. As of October 18, 2021, about 11% of RPS employees had neither secured vaccinations nor exemptions from vaccination, and unvaccinated employees could expect to start losing “one day of pay” in the forthcoming “pay period.” The docking of pay was “part of the progressive discipline process.” See page 4 of the superintendent’s four-page presentation, “Fall 2021 Reopening Updates,” dated October 18, 2021.

Three weeks later, on November 8, the school board voted 6-3 to gut the vaccine mandate by barring RPS “from docking or firing teachers who failed to comply” with the vaccine mandate. Indeed, “the School Board approved 29 resignations of staff, most of which were driven by the vaccine mandate, RPS’ chief talent officer, Sandra Lee, told the board.”

Then there is Wise County, Virginia, tucked away in the folds of the Appalachian mountains on the border with Kentucky.

Wise County –

Nestled in the heart of the rugged Appalachian Mountains, Wise County, Virginia offers an unmatched combination of natural beauty, outdoor recreation opportunities, a vibrant music and artisan scene, and abundant southern hospitality. Nature lovers, adventure seekers, music and art enthusiasts, foodies, families, and everyone in between will find something special in Wise County’s charming mountain towns.

To the stereotypical NPR-listening “coastal elites,” Appalachia is the stuff of people of “Scotch-Irish” heritage who “cling to guns or religion or antipathy towards people who are not like them … as a way to explain their frustrations.” (That was Barack Obama in 2008.) They succumb to addictions to locally-manufactured methamphetamines as well as to opioids, including streams of fentanyl coming across the southern border. These people correspond to Hillary Clinton’s “Deplorables” or to Barack Obama’s “bitter clingers”. The reality, of course, is like any reality. People get complicated and interesting and surprising really fast if one bothers to look and listen.

As I can see from the often terse and compact minutes of school board meetings, the school system has had to address issues about trans-genderism, Critical Race Theory, and COVID mitigation just like many other school district. (Interestingly, trans-genderism does not obviously show up in the Richmond records. Richmond is all-in on COVID theater but not the trans-gender business, it seems.) The Wise County school district has made a big point of monitoring COVID numbers, and it did impose mask mandates at one time or another, but I have yet to find hard evidence that the school system had imposed vaccine requirements on teachers. (See, for example, school board meeting minutes from August 10, 2021.)

There’s a tale of two school districts. Casual inspection suggests that there really are some adults out there who are navigating the fraught politics of education with some success and securing good results whereas Richmond City remains distracted with COVID theatrics. Does it use the cover of COVID to distract outside observers from its consistently and persistently poor, nearly bottom-of-the-bucket performance?

In a forthcoming piece I take up the experience of 130 school districts in a much richer dataset that spans the years 2010-2022.

See an ANOVA coming soon. Average income levels might be another factor. Collecting all these data is quite an effort. Such analyses on an even larger scale, a job for big data, ought to be happening. Governments have better access but I doubt the skills, or for the shame of it, the interest.