Climate Change and Forest Fires

Forest fires in the US peaked in 1930. By a huge margin. It is no contest.

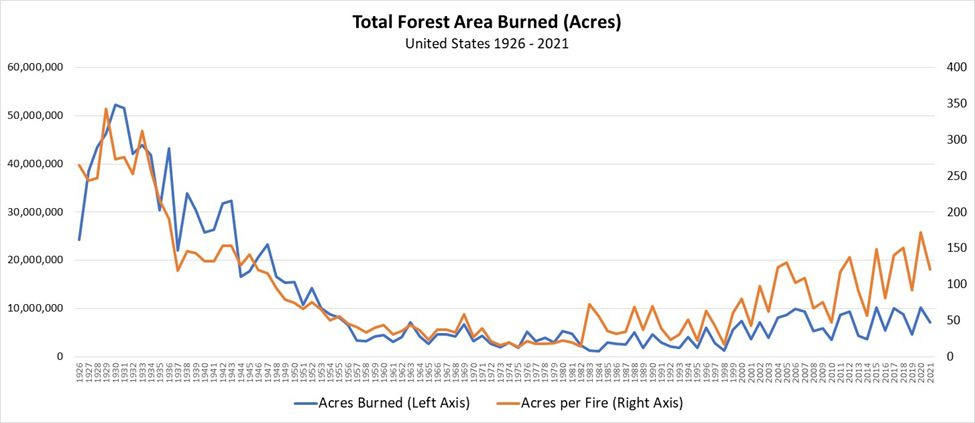

This essay is motivated by this graph:

The underlying data come from the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC). The data indicate the annual count of forest fires and the annual volume of acres burned from 1926 through 2021. (Ten million acres amounts to a little over 4 million hectares.) One can see that acreage burned exceeded 50 million acres (more than 20 million hectares) in 1930 and 1931. On average, total acreage burned has been simmering below 10 million acres per year over the last twenty years.

The media, meanwhile, tells us that the volume of forest fires has been increasing these last twenty years or so, Because Climate Change. Cue any number of recent installments from The New York Times. For example, “The Climate Connection to California’s Wildfires,” The New York Times, September 8, 2020:

While California’s climate has always made the state prone to fires, the link between human-caused climate change and bigger fires is inextricable, said Park Williams, a bioclimatologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “This climate-change connection is straightforward: Warmer temperatures dry out fuels. In areas with abundant and very dry fuels, all you need is a spark,” he said.

But, are we are also to understand that “human-caused climate change” induced the peak in forest fires in 1930? No, we are not. We are to understand that the modest rise in the volume of forest fires in the 1990’s was driven by human-caused climate change. And, as if to make the point, as of 2022, one can only secure data from the NIFC on the volume forest fires going back to 1983. I have NIFC data going back to 1926, only because I happened to download the data a few years ago. But, somewhere between 2019 and 2022, the NIFC made the data from 1926-1982 disappear. Because Science. (The original NIFC link, https://www.nifc.gov/fireInfo/fireInfo_stats_totalFires.html now redirects one to https://www.nifc.gov/fire-information/statistics/wildfires.) We can’t have people independently examining data, because they might “misinterpret” it.

Having made 1926-1982 disappear, the forest fire data look like this as of today:

One is invited to conclude that the volume of forest fires has increased dramatically. Because Climate Change.

The volume of acreage burned oscillated around 3 million acres per year through the 1980’s and 1990’s. From the year 2000 through 2014 or so, it edged up to about 7 million acres per year. Again, Because Climate Change. But given what a longer time series looks like, does this really make sense?

The New York Times may have always been committed to the climate change narrative, but even it would sometimes suggest that forest management could have something to do with the frequency and size of forest fires. Buried in a piece titled “Wildfires Are Worsening. The Way We Manage Them Isn’t Keeping Pace” (September 5, 2020), the Times averred:

For over a century, firefighting agencies have focused on extinguishing fires whenever they occur. That strategy has often proved counterproductive. Many landscapes evolved to burn periodically, and when fires are suppressed, vegetation builds up thickly in forests. So when fires do break out, they tend to be far more severe and destructive.

The Associated Press had, at one time, also said the quiet part out loud. From “Western Fires Spur Calls for Thinning Out Forests,” Associated Press, August 29, 1999:

Critics say they have long argued that the U.S. Forest Service should conduct more controlled burns and cutting to clear undergrowth that fuels wildfires, making them so hot they kill large trees that otherwise would likely survive.

Years of aggressive firefighting have allowed brush to flourish that would have been cleared away by wildfires, said Michael Paparian, a Sierra Club senior representative in Sacramento, Calif.

Dave Bischel, president of the California Forestry Assn., which represents the timber industry, said he agrees that the wildfires underscore the need for active forest management.

That bit about “making [forest fires] so hot they kill large trees that otherwise would likely survive” can inform how we think about news from just the last few days. The big sequoias in California got big, because they maintain mechanisms for surviving natural sequences of forest fires. But now the authorities worry that the sequoias might not survive fires that take hold after decades of artificially suppressing fires. “Yosemite's imperiled sequoias to be wrapped with fire-resistant foil,” reports a local Fox News affiliate on July 8. Such trees have been able to take care of themselves, each for more than a thousand years, but now they can’t? As the Los Angeles Times put it last year:

Giant sequoias are considered one of the most fire-adapted species on Earth, but experts say the drought-stressed trees are increasingly no match for massive, high-intensity blazes stoked by climate change and a buildup of dry vegetation in Western U.S. forests.

This was from a piece titled, “Wildfire reaches Giant Forest; fate of giant sequoias unknown,” Los Angeles Times, September 18, 2021. Concern about this kind of thing seems to well up with every dry season. California has its wet season (roughly November through April), and then it has its dry season (May through October). No accident, most big fires occur late in the dry season, but it seems that the sequoias have been doing just fine thus far notwithstanding the rise in media attention.

Meanwhile, it is here that I can cue our friends at the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC). I had already been meaning to craft a short essay about forest fires and forest management … or, rather, about how misaligned forest management has generated enormous fire hazards. And then PERC put out a very nice issue of PERC Reports titled How to Confront the Wildfire Crisis. It makes for compelling reading: https://perc.org/perc_reports/volume-41-no-1-summer-2022/.

At the very least, I recommend the opening, two-page essay. It is nicely crafted and compactly illuminates the big issues. See “The Big Burn of 1910 and the Choking of America’s Forests: Decades of fire suppression fuel catastrophic wildfires today” at https://perc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/PR-SUM22-220608-WEB-spreads.pdf.

PERC Reports does not identify any new mysteries, but it does illuminate things that get buried in the climate change rhetoric.

“The Big Burn” of 1910 “torched an unfathomable 3 million acres in western Montana and northern Idaho.” So, even under natural conditions, big fires might occur. The tragedy is that the Big Burn motivated radical, interventionist change in forest management policy.

After the Big Burn, forest policy was settled. There was no longer any doubt or discussion. Fire protection became the primary goal of the Forest Service. And with it came a nationwide policy of complete and absolute fire suppression.

The last century of fire suppression has left us with forests that are “over-stocked with fuel.” There is too much “wood in the woods.”

It is easy to imagine that allowing biomass to accumulate in the forests has contributed to the frequency of large fires since the 1990’s. It would also be easy to imagine that modest increases in average temperatures would contribute to fires. Less well appreciated, however, is the prospect that increasing carbon content in the atmosphere might induce biomass to grow more robustly and quickly. More carbon, more biomass, more stuff to oxidize.

Trees oxidize in two ways, fast or slow. When trees rot, they slowly oxidize and thus slowly return carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Burning trees amounts to oxidizing them quickly and returning carbon dioxide quickly to the atmosphere. Either way, slow or fast, oxidation constitutes but one part of the “carbon cycle.” And that’s why it is silly to think that planting a tree somehow amounts to “fighting climate change.” A tree borrows carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and, when it dies, it pays its debt back to the atmosphere with carbon dioxide. Thus, this idea of making one’s lifestyle “carbon neutral” by buying “carbon offsets” that depend on the planting of trees amounts to a shell game.

The long-run dynamic processes that generate a larger volume or smaller volume of forest fires involve a host of variables. Fires dissipate the volume of combustible biomass. But fires can regenerate forests which, in turn, yields more combustible mass some years down the road. Fire suppression can enable combustible mass to accumulate. Enhanced carbon content in the atmosphere can accelerate the growth of combustible biomass. All these things can contribute to the prospect of a greater volume of forest fires. The ultimate point, however, is that making glib appeals to “climate change” does not begin to explain why the volume of fires might be going up or down. And it definitely does not explain why the peak of forest fires occurred in 1930, more than 90 years ago.

A question remains about where the enhanced carbon content comes from. The journalistic narrative places all of the weight on the burning of fossil fuels. But there are larger, profound, inexorable processes at work. The journalistic view is that increasing carbon content generates some volume of warming. But, warming itself generates increasing carbon content. How? The oceans comprise the largest carbon sinks. In fact, they absorb a whole host of gases. But, warming will induce some volume of gases to come out of solution. (That is a consequence of Henry’s Law.) That leads to a question: What comes first: the dissolution of gases into the atmosphere, or the warming (by other sources) of the oceans? The journalistic narrative is that rising carbon content generates warming, but it may very well be the case the warming dwarfs that effect and induces higher carbon content.

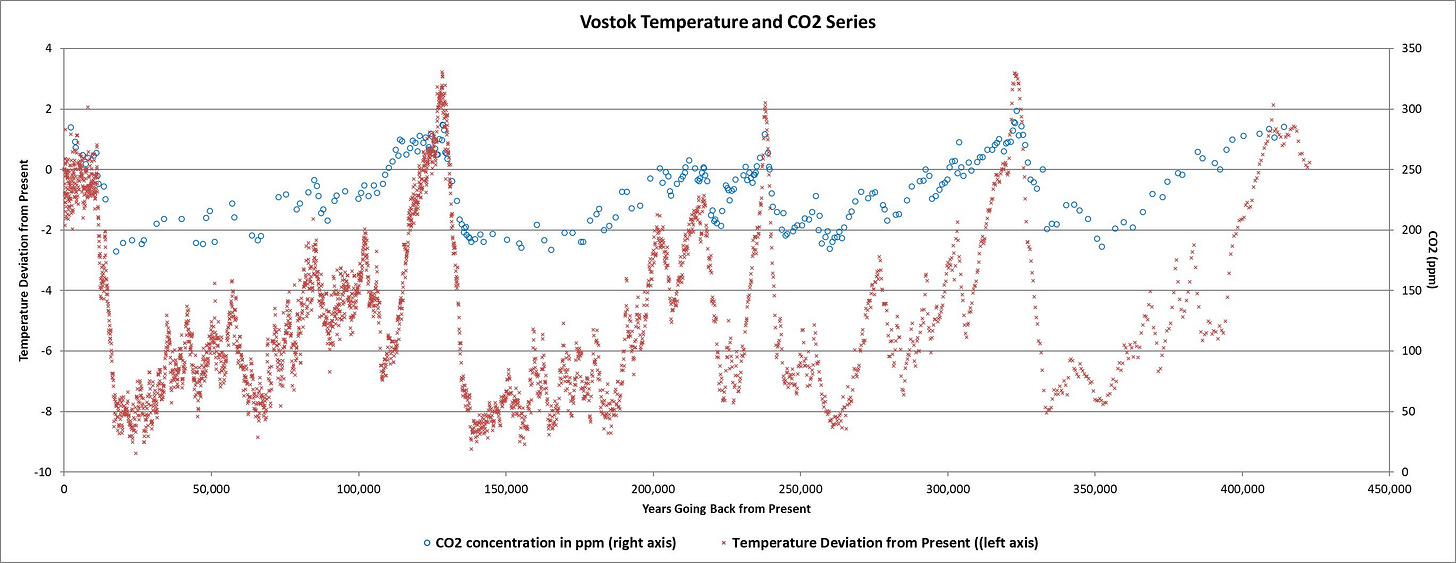

Warming may cause carbon concentrations to rise, not the reverse. (!) Or, there may be some weak feedback from carbon into warming, but warming from other sources may dominate. That is a subject for a separate essay, but the carbon and temperature series from the Vostok ice cores (Antarctica) go back more than 600,000 years and span many ice ages.

The Vostok data demonstrate that carbon content and temperature are correlated. Al Gore has exploited this point, but he implicitly assumed that carbon content drives warming. He did not accommodate the idea that there may be feedback between carbon content and warming, and he did not accommodate the idea that warming and cooling may drive carbon concentrations up and down. Alas, correlation is not causation. If anything, the Vostok data suggest that warming really does induce higher carbon content in the atmosphere, not the reverse; carbon concentrations may lag changes in temperature, and that time lag might be on the order of 1,000 years. 1,000 years.

If the majestic sequoias could talk, they might have some penetrating ideas and observations to offer. Indeed, they might have some ideas about where that warming comes from… Like, what is that blindingly shiny thing in the sky? That would be one place to start looking, but don’t ask the NIFC. According to the NIFC, 1983 is Year Zero.

There you go again, bringing in data! At the moment climate change is a religious movement because other religious movements around the notion of a supreme being are no longer in vogue. Whether we can get through this period of foolishness about our control over huge natural forces remains to be seen. The planet obviously has forces not fully modeled well with complex feedback loops not fully appreciated. But we see the effort in https://arstechnica.com/science/2006/02/2815/ where they walk the fine line of those forces.

The forces of anti-progress are tied into climate change. Forest management is needed only because we are trying to control nature. One think society ought to benefit by using some of nature's bounty if we are going to intervene. But we need to improve that. NM has seen disasters as a result of controlled burns that Western controlled.

Thank you for this excellent report which confirms what I already thought but had no proof.

Again I have no proof but I think the increase in the extent of fires in more recent years is due to human encroachment into areas which are vulnerable to fire anyway. I suspect that many of the fires are due to human activity either directly or indirectly.