Profiles in Resilience: Virginia schools that fought to restore in-person instruction after the advent of COVID

All schools in Virginia were forced to close in March 2020. But, those that opened to in-person instruction in the next school year made up the most lost ground. Other schools fell off the charts.

A more accurate title might have been “Schools in ‘red’ counties in Virginia were more likely to reopen to in-person instruction after the advent of COVID, and they tended to stem losses in performance induced by state-mandated shutdowns. ‘Blue’ counties were less likely to return to in-person instruction post-shutdown, and their performance in the state’s annual assessments tended to suffer the most and recover the least in the following school years.”

A more precise set of empirical propositions might be:

On average, public school students in counties that favored Glenn Youngkin (R) over Terry McAuliffe (D) in the 2021 gubernatorial election in Virginia have historically outperformed others in the state’s annual “Standards of Learning” assessments (SOL’s) before the advent of the coronavirus phenomenon.

The SOL performance gap increased conspicuously both during and after COVID. Red counties were more likely to mitigate performance losses, but the school systems of blue counties were more likely to fall off the charts.

Students’ performance in such red counties thus appears conspicuously more resilient in the aftermath of COVID.

Ultimately, traditional in-person schooling dominated remote online schooling. It was no contest.

These results hold up even after controlling for the relative wealth of each county (as measured by median household income) and for rural/urban distinctions (as measured by population density). These controls also yield some subsidiary results of their own:

The rural/urban divide does not illuminate differences in performance across counties, but …

More affluent counties do perform better than less affluent counties, which may not strike one as surprising. Even so, the result is interesting, because …

Red counties tend, on average, to be much less affluent than blue counties. But they still tend to outperform blue counties both pre and post-COVID—especially post-COVID. Other than resisting shutdowns, why would that be?

I opened this project with the idea of testing the proposition that that school districts that resisted calls to lockdown during COVID would have performed better than those that enthusiastically embraced lockdown and remote, online instruction. I do not have hard, county-specific numbers on lockdown policies. On top of that, the state government mandated the shutdown of all public school systems through to the end of the 2019/2020 school year. If all school systems had done the same thing through the entire coronavirus experience (close to in-person instruction), then there would be nothing to test. But, there is evidence that some school systems were more likely to open to in-person instruction and to shed COVID restrictions after June 2020. Thus, there is some very important diversity in COVID policies across school districts. That diversity can enable important tests.

I use Glenn Youngkin’s share of the vote in each county as a proxy for both resistance to mandates and enthusiasm for opening up. One can easily find commentaries that observe something to the effect that the fetishization of masks, vaccines, lockdowns and mandates really are a “blue” thing. Indeed, during the gubernatorial campaign, the Democrat candidate, Clinton protégé Terry McAuliffe, explicitly made a point of declaring that he would mandate vaccines for students and teachers were he to become governor. He further complained that opening up to in-person instruction was dangerous. (All of this comprised explicit points of contention in televised debates between McAuliffe and Republican candidate, Glenn Youngkin. Here is an example, a clip from the final debate.)

The fetishization of COVID would seem to complement the language of “trauma” and “harm” as well as the larger culture of risk-averse “safetyism”. I leave it to the reader to decide for himself why such correspondences would prevail—or to doubt whether they exist at all. That said, I did tap into a meeting of the board of the Richmond Public Schools. This was a Tuesday evening (August 23). The language of trauma, systemic racism, safety, and emotional distress were much in evidence in the comments of members of the public as well as in the comments of teachers and other education professionals. There might have been some faint hints of contrary interpretations, but much in evidence was the proposition that COVID amounted to a great pestilence and constituted such a shock to both students and to the school system that one should reasonably expect that student performance would inexorably and precipitously decline. That seemed to be accepted as an article of faith among most participants.

The fact that the school board had called a meeting at all might suggest that not everyone on the school board had bought into the COVID narrative. Indeed, the Richmond Times-Dispatch reported that the school board had called a special meeting to discuss candidate remedies to diminished performance. The board ultimately voted 5-4 not to replace the existing school curriculum with “a new internally developed curriculum … by the end of the 2022-2023 school year.” There had even been some question of whether the board would fire the superintendent, but the superintendent appears to have survived. The Blame-COVID-for-Everything crowd narrowly prevailed.

Earlier reports of the school district’s performance in the 2022 iteration of the state of Virginia’s “Standards of Learning” assessment tests (SOL’s) ostensibly motivated the call for a special meeting. Richmond has continued to lag the performance of three surrounding counties. An earlier report in the Richmond Times-Dispatch had featured this pair of graphs:

That report was “updated” on August 24. The graphs have been made to disappear (!). Good thing I had saved a copy of them. And, note what they show: The Richmond school district (red line) has consistently performed worse the last several years than the school systems in neighboring Chesterfield County (blue), Henrico County (yellow), and Hanover County (green). (Note that there are no test results for the 2019/20 school year. The state suspended testing in the spring of 2020.)

Chesterfield and Henrico have performed just about as well as each other, and both, like Richmond, experienced precipitous declines in performance between the 2019 SOL assessments and the 2021 assessments in reading and math. These two school systems trace out trajectories that parallel the Richmond trajectory but exceed the Richmond trajectory by nearly ten points or more year-by-year. Then there is the Hanover trajectory (green). Hanover also experienced something of a decline in performance, but the decline appears conspicuously modest. Hanover simply appears to have been much more resilient in the face of COVID lockdowns and mandates. Why would that be?

The local NBC television affiliate posted a report early in the 2020/21 school year that indicated that the Hanover County school system had opened for in-person instruction. “School officials ask for families to continue daily health screenings each morning and if kids are showing any signs of illness, they are required to stay home until they are symptom-free.” In contrast, the Richmond Public School system came out of the summer of 2020 ready “to begin a virtual school year.” It remained locked down.

Meanwhile, “Henrico Schools to follow Richmond’s lead and go with all-virtual fall semester” in 2020. Thus reported RVA Hub on July 20, 2020.

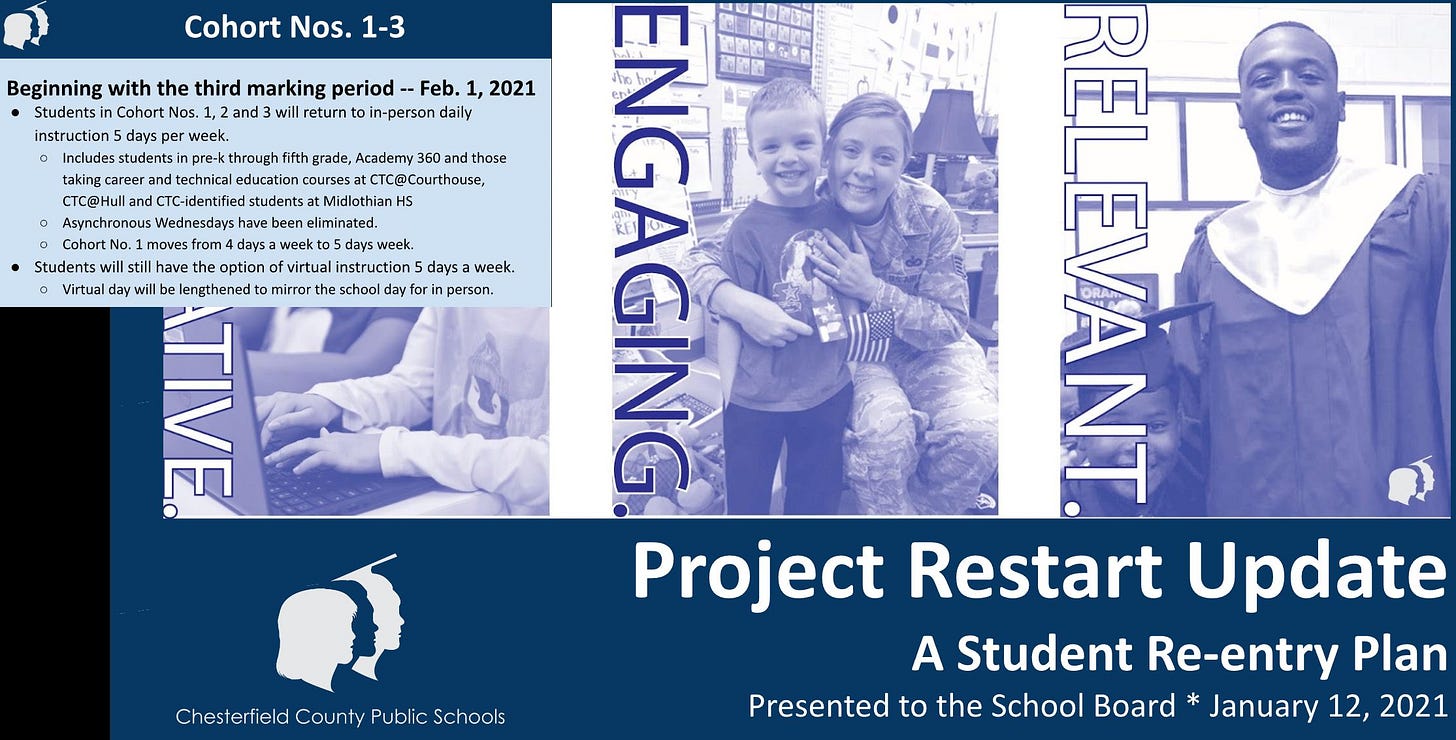

It appears that the Chesterfield County school system also remained closed to in-person instruction in 2020 but started to implement a partial opening by February 1, 2021:

The graphs in the Richmond Times-Dispatch derived from a little dataset comprising 20 data points (four school systems assessed over five years of SOL tests). The data appear consistent with the basic proposition: School systems that pushed back on lockdowns performed better through the course of the coronavirus panic. Meanwhile, the Youngkin vote shares over the four school districts (Richmond, Henrico, Chesterfield and Hanover) were, respectively, 20%, 40%, 51% and 68%. Thus, the one school system that was first to reopen (Hanover County) happened to perform best through the COVID experience and happened to be the reddest. Hmm…

A small dataset of 20 datapoints is all well and good, but, after much digging around, I did manage to download SOL assessment data for all Virginia school systems from 2006 through 2022. That data set spans 132 school systems and 16 SOL assessments and thus yields more than 2,100 system/year observations. The governor of Virginia, Ralph Northam (D), had imposed a state-wide closure of public schools in March 2020 through the end of the 2020 school year, but, coming in to the 2020/21 school year, some schools opted to open up whereas other persisted with lockdown. (One can see evidence of important differentiation across counties by examining the sequence of maps posted at Burbio’s School Tracker.)

Here is a graph that features all 132 school systems. It indicates the proportion of “passing” scores in the math SOL assessments from 2006 through 2022.

Note, first, the big drop in performance between the 2011 and 2012 assessments. The 2012 drop derives from the fact that the state made the math exam more rigorous. (The Roanoke Times reported this point just this last March 3, 2022.) It appears that the state reworked all five area exams over the years 2011-2013.

As far as mathematics go, note the bigger drop in most school systems’ performance between the 2019 and 2021 assessments. That is a manifestation of the shutdown effect. But the performances of some school systems deteriorated only marginally and subsequently recovered. The top seven performers (as of the latest 2022 assessment) were the school systems of Lexington City (blue and less affluent), Falls Church City (very blue and the most affluent), and Wise County (very red and much, much less affluent), Botetourt County (very red and affluent), York County (red and affluent), Washington County (very red and much less affluent), and Roanoke County (very red and much less affluent).

Top performers tend to be red or affluent, but Lexington City stands out as neither. Good for Lexington City. What did Lexington City do? It moved to at least partially open with in-person instruction. According to the local news in Lexington just before the start of the 2020/21 school year,

Lexington City’s school board met Wednesday night [August 12, 2020] to review its opening plans.

They decided to stick with their plans to open August 31, with some students attending in person. Although this is in contrast to a number of local jurisdictions that decided to open later and remotely, including surrounding Rockbridge County, administrators say they believe the low rate of COVID in Lexington and small classes will allow it.

More illuminating of post-COVID performance might be the next graph. It features the change, by school system, in performance from 2019 assessment (in math) to the 2021 and 2022 assessments.

No school system exceeded its 2019 performance in terms of “passes,” but some systems nearly recovered. The seven systems that performed closest to the 2019 benchmark were Lexington City (again, blues and less affluent), Falls Church City (very blue and very affluent), Craig County (very red and less affluent), Botetourt County (very red and affluent), Alleghany County (very red and less affluent), Salem City (very red and average income), and Highland County (very red and and much less affluent).

Which systems recovered the least by 2022?: Hopewell City (“purple” and less affluent), Charles City (purple and average income), Franklin City (blue and lower income), Roanoke City (blue and affluent), Madison County (red and average income), and Harrisonburg City (red and lower income).

I report the results of multivariate regression analyses of school system performance from 2006 through 2022 as measured by the SOL assessments. I gather SOL data from the Virginia Department of Education at https://www.doe.virginia.gov/testing/achievement_data/index.shtml . This link to the data was hard to find, and I had to download data in batches—they don’t make it easy, because they may want to frustrate researchers—but, for this essay, I did acquire data on the proportion of students securing a “pass” on SOL assessments in “mathematics,” “reading,” “writing,” “history and social science,” and “science.”

I paired the SOL assessment data with data on school system attributes. Most school systems align one-for-one with counties. One can thus speak of county school systems, but there are exceptions. With a little work, I was able to match school systems with county specific data on population density (from the Census Bureau), median household income (Census data from 2011), and the Youngkin vote share in the 2021 gubernatorial election (from our friends at Decision Desk HQ at https://results.decisiondeskhq.com/nov-2-2021-elections).

In a successive iteration of this work, I will examine thresholds of performance other than the proportion of students who had secured a “pass”. The SOL data include higher thresholds of “proficiency” and evidence of “advanced” skill. The data also break down results by race. But, for now I proceed with the proportion of all students who secured the lower threshold of “pass.”

In the analysis I include a dummy variable for “COVID” valued at 1 for the SOL assessment after 2020 and valued at zero for the SOL assessments pre-2020. I also interact the dummy variable with variables indicating median household income and the the Youngkin vote. I also interact the Youngkin vote with median household income. I end up ignoring rural/urban indicator (population density), because it does not add any explanatory power. (That is interesting in itself.) Finally, I “cluster” standard errors by school system. What does this all mean?

It means that, with a simple regression model, one can examine the following questions:

On average, did all counties tend to perform worse after the advent of COVID?

Did counties featuring higher Youngkin votes shares—redder counties—tend to outperform other counties pre-COVID?

Did redder counties tend to outperform other counties after the advent of COVID lockdowns?

Did redder counties tend to experience less deterioration in performance than other counties after the advent of COVID lockdowns?

Did more affluent counties tend to outperform less affluent counties pre-COVID?

Did more affluent counties tend to outperform less affluent counties of COVID lockdowns?

Did more affluent counties tend to experience less deterioration in performance than less affluent counties after the advent of COVID lockdowns?

Did more rural counties tend to outperform more urban counties pre-COVID?

Did more rural counties tend to outperform more urban counties after the advent of COVID lockdowns?

Did more rural counties tend to experience less deterioration in performance than more urban counties after the advent of COVID lockdowns?

That is a lot of action that a simple regression analysis can cover.

I run separate regression analyses for reading, writing, math, history, and science. And here are the results:

The rural/urban divide (as measured by population density) yielded nothing more than small and statistically insignificant results in multivariate analysis. That is a result right there: a county may be rural or urban, but the rural/urban distinction did not inform performance. I then excluded the rural/urban distinction in pared down regression specifications. Exclusion did not change any conclusions. Ultimately, all of the action pertains to the red/blue divide and the affluent/less affluent divide.

Reading –

Imagine the average county (“Average County”). It is average in that it yielded the average across all counties of vote share for Youngkin in the 2021 gubernatorial election, and it maintains the average across all counties of median household income.

83.8% of students in Average County, Virginia would have “passed” the reading SOL test (revised in 2013) pre-COVID.

Only 67.8% of students in Average County would have passed the reading SOL test post-COVID.

Now compare an otherwise average county with one standard deviation lower vote share to another otherwise average county with one standard deviation higher vote share. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 2.97%. Not a big result, but it is statistically significant.

Now compare an otherwise average county with the lowest vote share to one with highest vote share. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 6.6%.

Now compare a county with one standard deviation lower median income to one with one standard deviation higher median income. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 2.7%. Again, not a big result, but it is statistically significant.

Now compare an otherwise random county with the highest income to one with lowest income. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 7.1%

Writing –

81.2% of students in Average County, Virginia would have “passed” the SOL test in writing pre-COVID.

Only 60.2% of students in Average County would have passed the writing SOL test post-COVID.

Now compare a county with one standard deviation lower vote share to one with one standard deviation higher vote share. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 2.0%. That is a modest differential in performance, and it is not statistically significant.

Now compare an otherwise random county with the lowest vote share to one with highest vote share. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been an imposing 4.6%, but, again, this result is not statistically significant. In the case of “writing,” and only in the case of writing, redder counties did not discernibly stave off deterioration in performance much better than bluer counties.

Now compare a county with one standard deviation lower median income to one with one standard deviation higher median income. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 7.0%. That is a sizable differential, and it is statistically significant.

Now compare an otherwise average county with the highest income to one with lowest income. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been an imposing 18.5%. Wealthier people had fewer issues with school closures when it came to developing writing skills.

Mathematics –

84.2% of students in Average County, Virginia would have “passed” the SOL test in math pre-COVID.

Only 56.2% of students in Average County would have passed the writing SOL test post-COVID.

Now compare a county with one standard deviation lower vote share to one with one standard deviation higher vote share. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 6.4%. The result is statistically significant.

Now compare an otherwise average county with the lowest vote share to one with highest vote share. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been an imposing 14.3%. The result is large and is statistically significant.

Now compare a county with one standard deviation lower median income to one with one standard deviation higher median income. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 4.5%. The result is modest but is statistically significant.

Now compare an otherwise random county with the highest income to one with lowest income. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been an imposing 11.8%. The result is sizable and is statistically significant.

History and Social Science –

89.5% of students in Average County, Virginia would have “passed” the SOL test in history and social science pre-COVID.

Only 57.7% of students in Average County would have passed the writing SOL test post-COVID.

Now compare a county with one standard deviation lower vote share to one with one standard deviation higher vote share. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 5.7%. The result is sizable and is statistically significant.

Now compare an otherwise random county with the lowest vote share to one with highest vote share. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been an imposing 12.7%. The result is sizable and is statistically significant.

Now compare a county with one standard deviation lower median income to one with one standard deviation higher median income. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 6.0%. The result is sizable and is statistically significant.

Now compare an otherwise random county with the highest income to one with lowest income. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been an imposing 15.7%. Wealthier people were able to keep up with their history after the advent of COVID.

Science –

86.2% of students in Average County, Virginia would have “passed” the SOL test in science pre-COVID.

Only 58.1% of students in Average County would have passed the writing SOL test post-COVID.

Now compare a county with one standard deviation lower vote share to one with one standard deviation higher vote share. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 5.6%. The result is sizable and is statistically significant.

Now compare an otherwise average county with the lowest vote share to one with highest vote share. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been an imposing 10.3%. The result is large and is statistically significant.

Now compare a county with one standard deviation lower median income to one with one standard deviation higher median income. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been 5.6%. The result is sizable and is statistically significant.

Now compare an otherwise average county with the highest income to one with lowest income. The difference between these two counties post-COVID would have been an imposing 14.7%.

Anyone can re-engineer these results with the coefficients and summary statistics from the following two tables that I have posted here:

It was in science, history and math that the performance of Average County has deteriorated—by roughly 30 points—with the advent of COVID. Average County also suffered losses of about 20 points in reading and writing.

In contrast, counties that moved more assertively to open schools—the redder counties—had tended to outperform other counties pre-COVID by several points, and they proceeded to discernibly expand the performance gap in all fields except writing. Stated in the reverse: On average, redder counties went far towards holding their own after the advent of COVID, but bluer school systems allowed themselves to fall off the charts. They fetishized masks, shutdowns and vaccines. They imposed the costs of all these things on children so that (still employed) teachers and school administrators would not have to bear the phantom hazards of showing up at work.

The same goes for wealthier counties across all five SOL assessments. Wealthier counties were more likely to hold their own after the advent of COVID, but less wealthy counties were more likely to allow themselves to fall off the charts.

Taken all together, red counties were more likely to stanch the bleeding and recover whereas less affluent, blue counties performed abominably. They closed their schools to in-person instruction and kept their schools closed. Their students performed abysmally.

Ultimately, the move to remote, online instruction crushed performance, but schools could have spared themselves such diminished performance had they preserved in-person instruction. In the early going (the first half of 2020), school systems state-wide could not escape state-mandated lockdowns. But, with the new 2020/21 school year, some school systems moved to open to in-person instruction. The school systems that remained closed amorphously blame COVID for their poor performance, but the performance of counties that opened reveals the lie: All school systems would have performed at pre-COVID levels had they not locked down at all. Richmond and other such counties have nothing to blame but their own bad judgment.

Had Glenn Youngkin not won the gubernatorial election, the incoming governor, Clinton protégé Terry McAuliffe would have moved to impose more restrictions on schools. He made a big point of doing just that during the campaign. But, it is to the credit of the new administration that it did not do not impose more restrictions and requirements. Rather, the Youngkin campaign distinguished itself by taking on concerns about “education.” But that almost did not happen. A listless, risk-averse, do-nothing campaign did not motivate the “education” issue. Rather, the education issue found the campaign, and the campaign had just enough gumption to run with it.

Parents in very, very blue and very affluent Loudon County right outside of Washington, DC started speaking up in their school board meetings against the implementation of Critical Race Theory in their children’s curricula. They had not paid attention to school curricula before, but, with schools closed and their children doing school work online at home, they finally got a first-hand view into the content that the Loudon County school system had been channeling into their kids’ minds. Parents started to organize and speak up. They even attracted the attention of the Biden Administration, which subsequently instructed the Department of Justice and the FBI to harass and investigate Loudon County parents.

So, here were parents who were mostly solid blue Biden voters being harassed for speaking up. And a pivotal group of them who had voted for Biden in 2020 ended up voting not for the Democrat (McAuliffe) in the 2021 gubernatorial election but rather voted for the nominal Republican Glenn Youngkin. The election was tight, but Loudon County swung ten points from the 2020 to the 2021 election in favor of Republicans. That ten-point swing in Loudon County comprised the entire winning margin in the election. One would think that there would be a lesson in that result for Republicans, Democrats or any other politicians. But will such typically do-nothing politicians see the lesson, absorb the lesson, and act on it?

An opportunity of no making of its own fell into the lap of the Youngkin campaign. The campaign gets credit for taking advantage of the opportunity. It made the difference between winning and losing. And winning kept the Democrats from doing what they wanted to do: impose vaccine mandates on “students, teachers and health care workers” and impose more gratuitously racialized curricula.

Thanks for quite an analysis. Richmond demographics are unlike the surrounds as I recall. And Hanover has since the beginning of the nation been quite a bulwark of independent thought! I do hope this gets shared with Ms Guidera and her crew. And it really needs national attention.

(My family background is among the First Families in VA).

Here in NM, I lamented the closures enough to get me booted from some platforms. NM is a poor state with severe educational needs both for children and many parents. Schools are the best way out of poverty. The State made not even minimal effort to keep Title 1 schools open even for Special Ed students. This will hold back progress for another generation, my guess. All because of fear that never was rational. Sadly, I believe it also revolved around the politics given the total blue adherence. The Governor was highly praised by adopting and exceeding the CA approach. The praise died away as many perished in our NW corner because of cultural factors related to our native population. We could have avoided that with more community support that came way too late. NM managed to be tops in mortality/population. The restrictions of course did little and management keep them long after knowing how ineffective they were. I doubt the politicians will ever be held to account, but am hopeful.