Who’s Afraid of CO2?

Carbon dioxide emissions may be contributing to atmospheric concentrations of CO2. Or not. But, so what?

By the time The Population Bomb (Paul Ehrlich 1968) had come out, catastrophism had already gone mainstream. First there were the books, and then came the films inspired by the books such as The Planet of the Apes (1968): At the end of the film, Charlton Heston learns that humanity had managed to destroy civilization and bequeath a war-ravaged planet to the apes. In Omega Man (1971), Charlton Heston gets to observe the aftermath of humanity having destroyed civilization by way of biological warfare. In Soylent Green (1973), humanity has not yet gotten around to destroying its noxious civilization, but Charlton Heston discovers the schemes the central authorities have instituted for mitigating over-population. Among other things, the authorities would randomly nab crowds of people and haul them off to be recycled.

That made for quite a run of films for Charlton Heston, but then there was Logan’s Run (1976) with Michael York: A post-Apocalyptic pocket of humanity manages to engineer paradise and encapsulate itself within a bubble.

Sometime in the 23rd century … the survivors of war, overpopulation and pollution are living in a great, domed city, sealed away from the forgotten world outside. Here, in an ecologically balanced world, mankind lives only for pleasure, freed by the servo-mechanisms which provide everything.

But, the central authorities perceive that maintaining paradise-in-a-bubble requires active regulation of population in the bubble, hence its scheme for disposing of whole cohorts of people: “Life must end at thirty unless reborn in the fiery ritual of carrousel.”

What do these films have in common? Perhaps they span many shades of Malthusianism in that there may be over-population and then near extinction, but principally these films seem to operate out of the premise that humanity does a poor job of managing its affairs. The world is good, humanity is bad, and the world would be a better place without humans crawling all over it like cockroaches.

An appealing feature of Malthusianism is that it is almost impervious to the evidence. Population increases: Sound the alarm! Population decreases: We told you so.

Back in the early 21st century, current day Malthusians endeavor to pack the rest of us into 15-minute bubbles, Because Climate Change. Some years earlier, someone over at The Economist died, and a new clique neo-Malthusians assumed control of the editorial voice of the magazine. The new rule seemed to be, “Open every piece with the phrase, ‘Because of climate change …’”

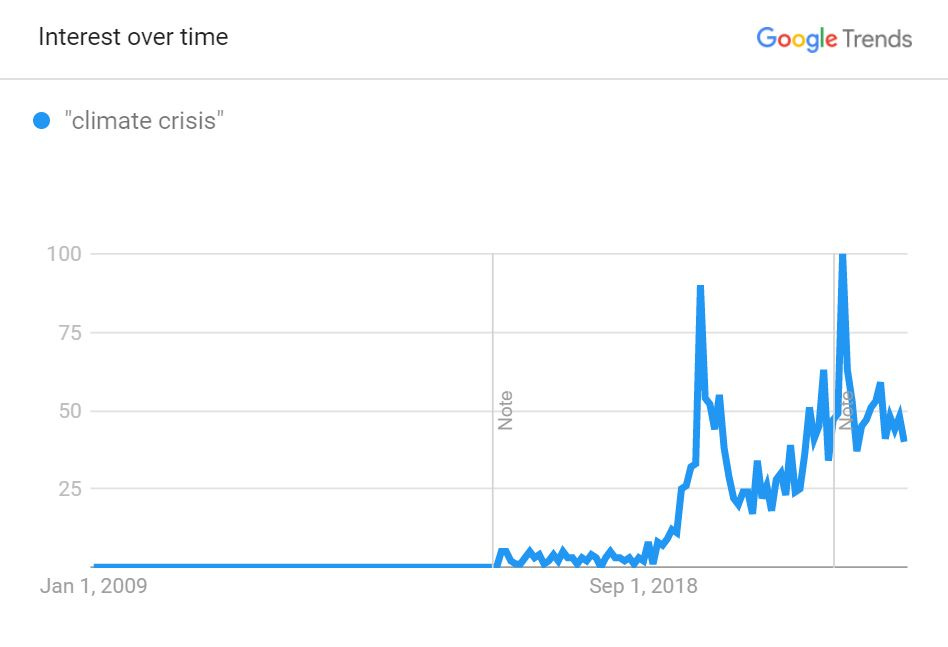

And, obviously, the fictional “climate crisis” is “an LGBTQIA+ issue,” because “People who are already vulnerable and marginalized are more likely to experience the greatest impacts of the climate crisis.” Never let a manufactured crisis go to waste.

This essay is motivated by this graph:

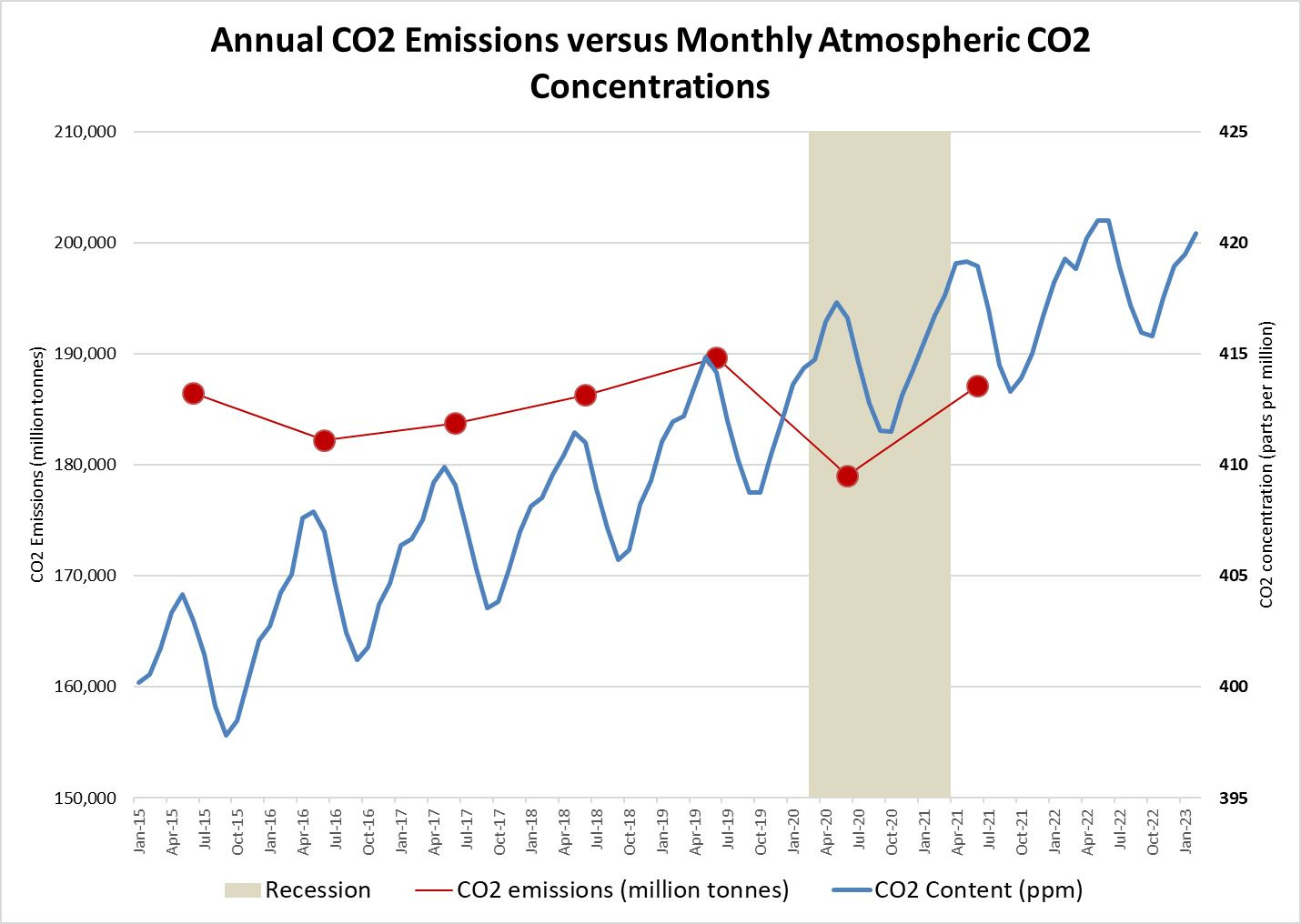

I get annual emissions (metric tons/tonnes) from our friends at Our World in Data: https://github.com/owid/co2-data

CO2 concentrations (parts-per-million) are measured monthly at the Mauna Loa Obervatory in Hawaii: https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/

Monthly measurements of CO2 concentrations exhibit obvious seasonality, reaching a peak each year in late spring and a nadir in late summer. This seasonality probably reflects the fact that most vegetation lies in the northern hemisphere. In the spring and summer of the northern hemisphere, plants and trees absorb carbon dioxide. In fall and winter, they give back some of that carbon dioxide by shedding leaves. Dead leaves slowly oxidize and generate some volume of CO2.

Seasonality is interesting. No less interesting is the fact that CO2 concentrations have increased by about 3 parts-per-million (by about 0.7%) year after year. But, what is driving that steady annual increase? Hold that question.

From 2015 through 2021, global carbon emissions averaged about 185 billion tonnes and exhibited some variation. Most notably, COVID lockdowns induced a decline in emissions from about 190 billion tonnes in 2019 to less than 180 billion tonnes in 2020. So, global emissions declined nearly 6% in 2020, but CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere continued to increase without an obvious hiccup. Should we have expected CO2 concentrations to decline in 2020? Or should we have expected a lag of one year, in which case CO2 concentrations should have declined in 2021?

The real question is for the proponents of “anthropogenic climate change”. Their story, of course, is that CO2 emissions contribute to CO2 concentrations, and rising CO2 concentrations induce global warming … except when we get unseasonably cold weather, in which case it’s just weather or, worse, we call it “climate change”. But, the question is, if CO2 emissions have been flat for seven years, then shouldn’t CO2 concentrations have also been flat? Or is something else driving CO2 concentrations? More importantly, does that something else comprise processes that are well outside humanity’s control?

Now, the reader may note that, in composing this graph, I’ve been a little cheeky in having selected the interval January 2015 through February 2023. The trend in annual, global CO2 emissions was essentially flat over that interval. It turns out, however, that the trend over a much longer interval is distinctly positive. Consider the following graph.

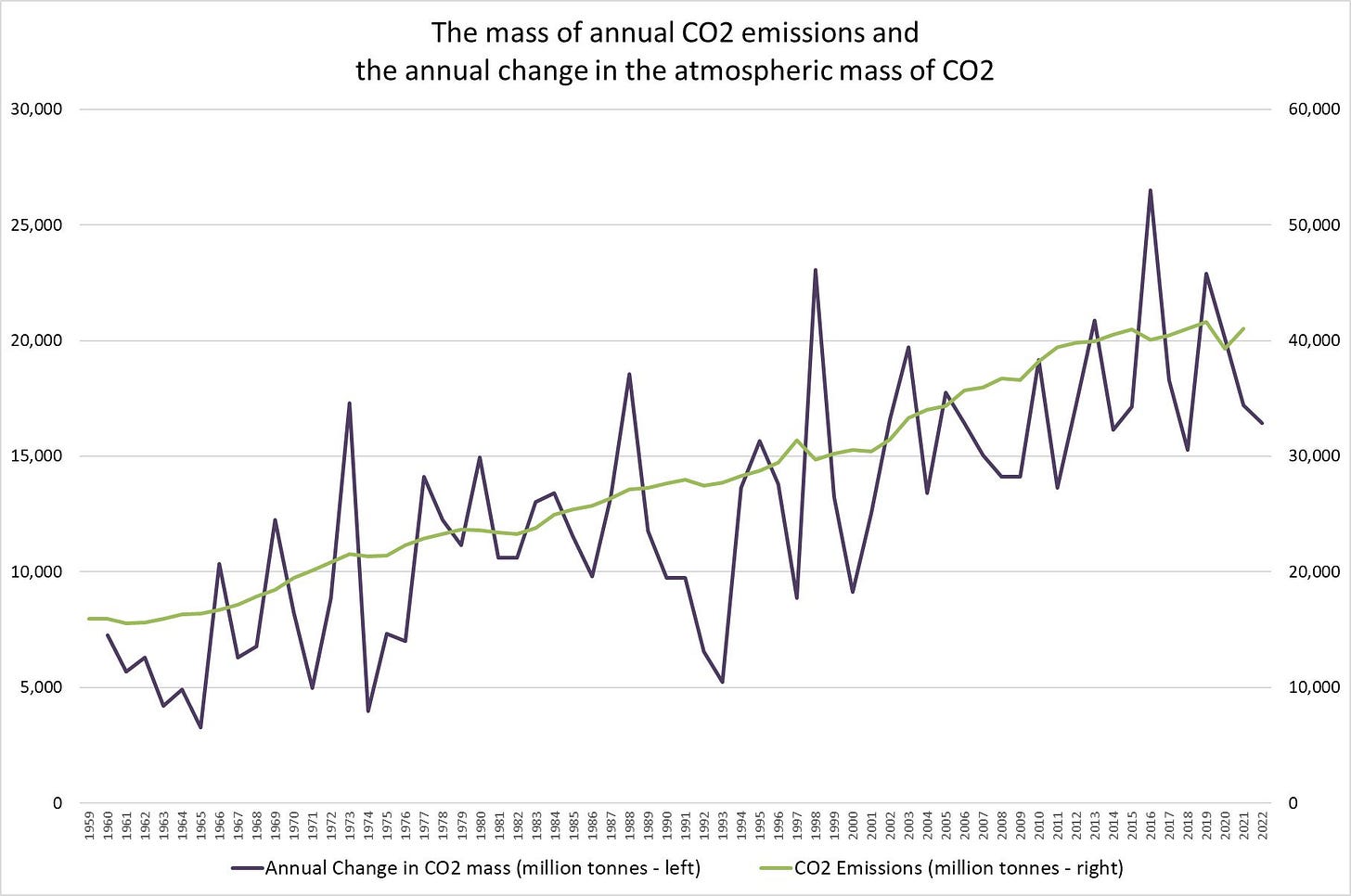

From 1958 through 2022, CO2 emissions have more than doubled from a little over 80 billion tonnes per year to a little over 180 billion tonnes per year. CO2 concentrations, meanwhile, increased from about 315 part-per-million to 418 parts-per-million. Note, however, that CO2 emissions have advanced fitfully whereas CO2 concentrations have advanced much more smoothly. Specifically, emissions have been flat over many intervals, each spanning several years. Emissions have yet increased markedly over other intervals. CO2 concentrations, meanwhile, have increased steadily. There may have been a bit of a break in the rate of growth in the early 1990’s, but overall, CO2 concentrations have tended to increase at an increasing rate.

So. Do CO2 emissions drive CO2 concentrations? The evidence from the Vostok ice core series suggests that temperature drives CO2 concentrations. (Wait. What?) Over an almost geological scale of time, CO2 concentrations appear to lag changes in temperature by about 800 years. Why might that be? One mechanism would be: The oceans constitute the most important carbon sinks, but, if you warm up the oceans, carbon dioxide comes out of solution and contribute to CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere. Alternatively, if the gods cool the oceans, then the oceans draw more CO2 from the atmosphere, and atmospheric concentrations go down. But, what if over the course of a just a few centuries, we introduce more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels. Shouldn’t that yet increase concentrations? Possibly. Or possibly not. Let’s do some accounting.

It turns out that we can easily get information on the total mass of the atmosphere (in kilograms, say) as well information on atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide on a parts-per-million basis. But, we would like to convert parts-per-million to mass, and we could then figure out whether the mass of CO2 being injected into the atmosphere each year operates at the same scale as increases in atmospheric concentrations of CO2. How to do this?

NASA tells us that the atmosphere occupies a mass of about 5*1018 kilograms. On a parts-per-million basis, N2 and O2 (nitrogen and oxygen) occupy about 80% and 20% of the atmosphere, respectively. Now, a nitrogen atom is comprised of a combination of neutrons and protons totaling, all together, 14 in number. Neutrons and protons occupy just about the same mass, which is why we say that a nitrogen atom (N) occupies an atomic mass of 14 and why atmospheric N2 thus occupies an atomic mass of 28. Meanwhile, O2 occupies an atomic mass of 32. Taken together a “mole” of air has an atomic mass of about (0.8*28 + 0.2*32)*Avogadro’s Number = 28.8*Avogadro’s Number. Meanwhile, CO2 occupies about 0.04% of the atmosphere on a parts-per-million basis, and CO2 occupies an atomic mass of 44. Thus, atmospheric CO2 occupies about 0.0004*(44/28.2) ~ 0.06% of the mass of the atmosphere. The mass of CO2 in the atmosphere thus comes out to about 3*1015 kilograms.

Now, we can go ahead and estimate the mass of annual CO2 emissions and annual increases in the mass of atmospheric CO2, and we can do this year by year. What do we get?

The mass of CO2 emissions (green) is on the right axis, and the annual change in the mass of CO2 in the atmosphere is on the left. Note that CO2 emissions are about twice as large as the annual increases in CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere. CO2 emissions vastly exceed increases in CO2 concentrations … Interesting.

It would be hard not to suggest that the burning of fossil fuels has not contributed to atmospheric concentrations of CO2, but two points:

(1) CO2 emissions may yet not have much influence on CO2 concentrations. Larger processes may be at work, and those processes may be so large that they actually dwarf the contribution of CO2 emissions. It would be good if we could sort out what is really going on.

(2) Whether or not CO2 emissions are contributing importantly to atmospheric concentrations, we can see that at least half of those emissions are being sucked out of the atmosphere. Big forces really are at work.

I lied. There is a third point.

(3) So what?

Why should we care about CO2 emissions? According to the climate change crowd, we should care deeply about emissions, because (they claim) emissions will induce desertification, the destruction of agricultural productivity, global famine, coastal flooding, a greater volume of forest fires as well as a greater volume of violent weather. Except that none of this has happened. Here is a piece, for example, that I had composed about forest fires:

Climate Change and Forest Fires

This essay is motivated by this graph: The underlying data come from the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC). The data indicate the annual count of forest fires and the annual volume of acres burned from 1926 through 2021. (Ten million acres amounts to a little over 4 million hectares.) One can see that acreage burned exceeded 50 million acres (mo…

But, here are other (and, I would suggest, superior) reasons we might care about CO2 emissions:

CO2 is plant food.

CO2 has been coming out of solution (from the oceans), and the earth has been “greening.”

Oxidizing hydrocarbons (fossil fuels) yields H2O and CO2. That doesn’t sound so bad. Who knew?

CO2 emissions decreased during “lockdown” and during the “Great Recession,” and, yet, CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere continued their linear increase. No hiccups or anything. It just kept creeping up. Perhaps larger forces are at work.

CO2 is yet a trace gas and hovers above historically low levels.

The “carbon cycle” seems poorly understood. Doing some accounting of it just raises more questions. Meanwhile, the authorities have come to understand carbon dioxide as a pollutant, as something to be sucked out of the atmosphere, when, in fact, it really is a gift from the gods.

So, everyone, take off your masks. Stop increasing carbon dioxide concentrations in your own blood stream. Get outside. Get some fresh air. And harness the power of CO2 in your garden.

Excellent article. I'm sure my kids roll their eyes when I mention articles such as yours. Young people seem to be much more believing than they used. Aren't kids supposed to be the sceptics? "But what about the science?" they say and roll their eyes some more. It's just dad reading too many conspiracy theory books. There was a time when I was deeply pessimistic about the future but now I'm the opposite. There are many problems but the world is still a much better place than it was even 70 years ago when I was born. People should be reminded of that.

From what I understand there are two targets for global warming, an ambitious one of 1.5C and a less ambitious one of 2C. Last time I looked we were already more than 1 degree above historic temperatures but really hardly anything has changed. None of the terrible predictions have happened. It's true that winters are a little milder and summers are a little warmer although you wouldn't think that today in the UK. It's chilly. When I hear the climate activists they seem to be expecting that when we reach the 1.5C that'll be the end, like a cliff edge. They talk about tipping points all the time, telling scary stories like kids around the camp fire.

I thought you might be interested in this if you haven't already seen it https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sgOEGKDVvsg

It's a talk given by Mark Mills from the Manhatten Institute to a Danish Investment fund called Skagen. He explains why the transition from Fossil Fuels to renewables is not possible because we can't mine the minerals needed fast enough ( by a long way). It made sense to me and I think Mark Mills and the Manhatten Institute are respectable bodies.

Reassuring thesis, reasonably voiced.

Is science, in the manner of a religion, putting humanity at the centre of the climate disaster universe and missing 'big forces'?

Original sin. We just love to hate ourselves.